On 9th January 1684, the eminent London writer John Evelyn wrote in his celebrated diary: 'I went across the Thames on the ice, now become so thick as to bear not only streets of booths, in which they roasted meat, and had divers shops of wares, quite across as in a town, but coaches, carts, and horses passed over. So I went from Westminster stairs to Lambeth, and dined with the Archbishop.'

Evelyn was describing that winter's 'great frost'. The severe weather – the worst in a sequence of harsh winters – lasted two months until thawing in early February. During that time the Thames in central London was transformed into a thoroughfare on which animals, vehicles and humans travelled. It was popularly dubbed 'Freezeland Street'.

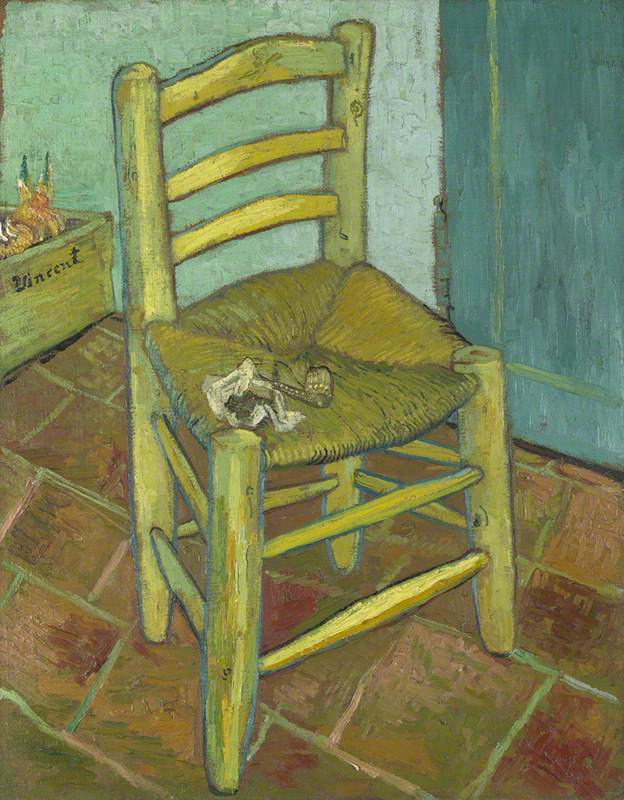

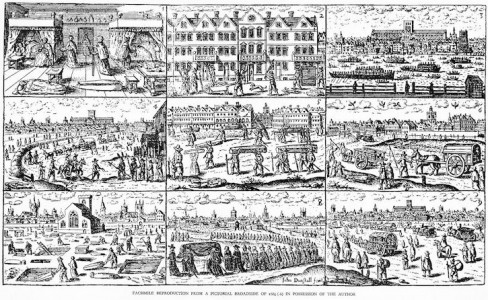

Frost Fair on the Thames, with Old London Bridge in the Distance

c.1685

unknown artist

The event was not unprecedented. The river had already frozen during eight winters since 1608 and would do so once more before the century ended. The earliest account of an icebound Thames appeared in AD 250 and wheeled traffic took to the river as early as AD 923. In 1410 the freeze lasted 14 weeks and reliable records of organised entertainments date from 1309. In 1564 chronicler Raphael Holinshed described boys playing football on the ice 'as boldly there as if it had been on dry land'.

Two factors especially made the recreations possible. One was climatic: from the fourteenth century until around 1850, the so-called 'Little Ice Age' gripped Europe as far as the Mediterranean with periodic Arctic winters. Not only rivers froze, the coasts bordering the southern North Sea were also affected. As well as merriment, the severe weather brought hardship, especially to London's poorer inhabitants. Food prices rose, supplies faltered and wood for heating became scarce. The Great Frost of 1683–1684 coincided with an outbreak of smallpox in London.

The other factor was man-made. Old London Bridge spanned the Thames between the City and Southwark and over centuries a cramped and crowded street of townhouses, shops and religious foundations had been established along its length. The river was wider and shallower than it is today and the bridge stretched across 20 closely spaced stone piers between which water raced. The arches that the bridge was built on rested on vast timber breakwaters or 'starlings' that further narrowed the river's flow.

Consequently, as water froze at the shallow riverbanks in severe winters, chunks of ice broke away on the sluggish current and were caught in the increasingly congested openings of the bridge. The river was so impeded as the tide ebbed that the ice compacted and thickened, quickly spreading across its expanse for some distance upriver, at least as far as Lambeth Palace almost three miles away. London's primacy among its European neighbours as a maritime trading centre then came to a virtual standstill. Boats were locked solid in the ice and workers were laid off in what became known as the 'dead vacation'.

At that point, human ingenuity and enterprise speedily intervened. The extraordinary phenomenon known as the frost fair bustled into life, the first of which is known to have taken place in 1608. 'Coaches plied from Westminster to the Temple,' wrote Evelyn, whose curiosity drew him back to the festivities on 24th January 1684, 'and from several other stairs to and fro, as in the streets, sleds, sliding with skates, a bull-baiting, horse and coach-races, puppet-plays and interludes, cooks, tippling, and other lewd places, so that it seemed to be a bacchanalian triumph, or carnival on the water'.

Similarly attracted to the spectacle was the artist Abraham Hondius. Settled in London for at least ten years after leaving his native Holland and now in advanced middle age, Hondius probably witnessed the commotion of the fair first hand. Not surprisingly, he saw the artistic and maybe commercial potential of depicting the fairgoers' antics on canvas. Perhaps he made mental notes as he patrolled the ice and maybe even drew outline sketches with chilled fingers, although no studies exist. He might also have examined the illustrated printed broadsheets published for widespread distribution at the time, or absorbed written and spoken tales by observers like Evelyn.

A Frost Fair on the Thames at Temple Stairs, London

1684

Abraham Hondius (c.1625–1691)

But unlike those sources, Hondius' panoramic painting A Frost Fair on the Thames at Temple Stairs is imbued with a wintry atmosphere. The conditions that year must have been exceptionally memorable. Evelyn commented on 1st January that 'the air was so very cold and thick, as of many years there has not been the like', and Hondius wraps his scene in a frigid wintry light that plays across chill, slate-like tones.

In addition to its panorama of gestures among the numerous groups of animated characters, the painting has two outstanding features. The first is the centrepiece of the composition: the double column of temporary stalls under rippling banners snapping in the wind. The cortège of canopies advances in a graceful shallow arc from the Temple side of the river in the distance to stop just short of the Southwark bank, the vantage point of the image.

According to a contemporary broadsheet, the stalls – assembled on a framework of ferrymen's redundant oars over which tradespeople draped blankets – sold 'all sorts of goods imaginable, namely cloaths, plate, earthen ware, meat, drink, brandy, tobacco and a hundred sorts of other commodities not here inserted.'

The lengthy queue extending off to the right of the picture is evidence of the market's popularity, while near the north bank beyond, spectators gather in a wide circle, perhaps to watch one of the animal blood sports mentioned by Evelyn and other witnesses. On the left of the stalls is a masted boat, stranded mid-river, with sail raised and flags flying. Its deck may have become the stage for performances with puppets or actors, or the site of an impromptu fairground ride.

The second notable attribute of this painting is Hondius' decision to turn his attention away from the substantial architecture of the city on dry land. Its details are perfunctory, the buildings as intangible as stage scenery with windows reduced to minimal vertical rhythms. The real London – by then on the verge of becoming the largest city in western Europe – appears featureless and deserted while the 'alternative world' of transient fragile structures, upon he lavishes attention, acquires the illusion of permanence as crowds of people circulate purposefully round them.

The density of the ice was naturally a concern for everyone who descended the riverbank, having first paid his or her fare for admission to a ferryman, to step onto the river's frozen surface. Although the ice is never thought to have exceeded a robust 11 inches in thickness, Hondius applies artistic licence to his depiction, piling grander blocks in the right foreground, perhaps intentionally recalling his painting of The Frozen Thames Looking Eastwards towards Old London Bridge.

The Frozen Thames, Looking Eastwards towards Old London Bridge, London

1677

Abraham Hondius (c.1625–1691)

Completed in 1677, when the Thames also froze, the picture conveyed a quite different vision of the river – a polar wasteland dwarfing men and animals as they clamber over giant cubes of sea ice under a bold and threatening sky.

The frozen river, for its brief duration, may even have simplified travel through the chaotic medieval city. The Tudor lawyer Edward Hall reported in his chronicle that Henry VIII and Queen Jane Seymour rode across the river's surface to Greenwich in 1536, while tradition has it that Elizabeth I frequently took to the ice. Charles II was reputedly keen on visiting the fair. One Victorian biographer of London alleged the king joined in a fox hunt on the Thames, and a French traveller present in London at the time stated that on one occasion Charles passed a whole night upon the ice.

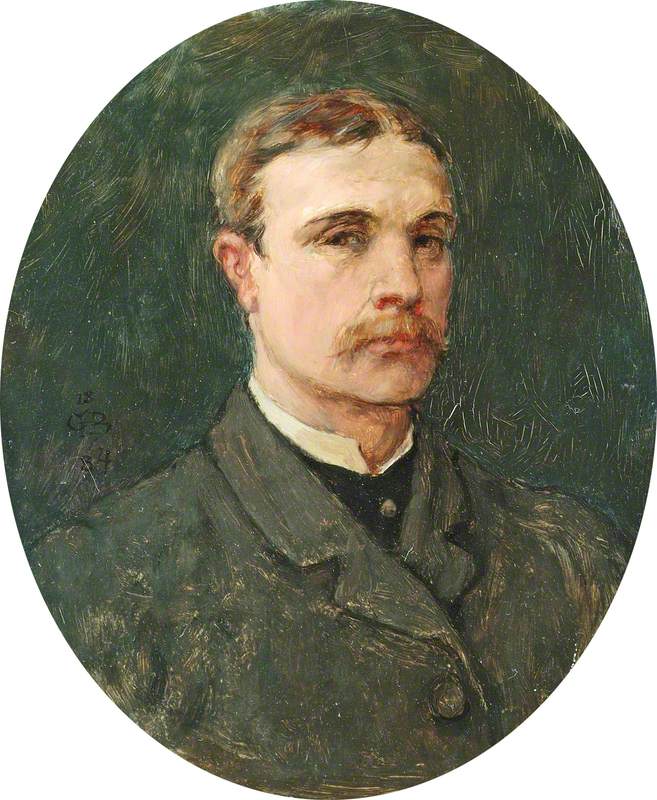

The monarch may have been attracted to particular stalls, such as the printing presses set up on the ice where, according to Evelyn, 'the people and ladies took a fancy to have their names... and the day and year set down when printed on the Thames; this humor took so universally that it was estimated the printed gained £5 a day, for printing a line only'. On 31st January 1684, the printer G. Croom signed a decorative card he produced naming members of the royal family. Perhaps Charles bought one, a possibility that appealed to Henry Gillard Glindoni, an artist who specialised in depicting historical dramas, because he depicted the king with his entourage at the fair flamboyantly perusing a sheet pulled from a nearby press.

Unlike Hondius, the painter of this scene was not a contemporary of the event. Glindoni made the painting in 1900, demonstrating a delight in ornate and colourful costumes from bygone eras that probably exceeded strict period accuracy. Even the name by which he was known to the Royal Academy and other London institutions where he regularly exhibited after 1872 was embellished with an exotic flourish: Glindoni had been begun life as Henry Glindon not far from the Thames at Kennington.

By then the frost fair had been consigned to history. The last fair closed in 1814 when the river ice thawed after four days in early February. The demolition of Old London Bridge in 1834 and its replacement by a new structure with fewer piers and wider arches meant that the Thames flowed freely in winter.

Then, with the embankment of the north and south banks through central London in the 1860s, the tidal river became deeper and narrower, eliminating the risk of a future Great Frost. Perhaps that accounts for the wistful mood pervading The Frozen Thames in which Victorian artist Walter Greaves, himself a Chelsea boatman devoted to the Thames, shows two snow-dusted boats beached on a bed of ice beside the flowing river. An elegy, of sorts, for former grandeur.

Martin Holman, writer