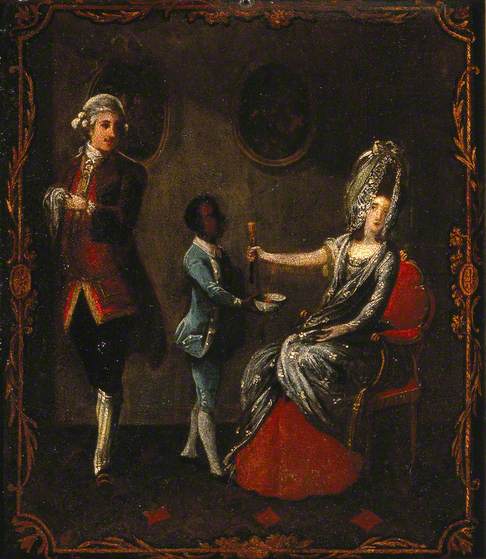

Completed British 18th C, except portraits, Dress and Textiles, Portraits: British 18th C 28 comments Could this painting depict Philadelphia physician Dr John Kearsley and his slave James Derham, or is it a generic scene?

Photo credit: Wellcome Collection

I wonder if this painting could represent a scene from the life of Philadelphia physician Dr John Kearsley (1684–1772) and his slave James Derham (c. 1762–after 1801)? James Derham was owned by at least three doctors: Dr Kearsley; Dr George West, surgeon of the Sixteenth British Regiment during the American Revolution; and Dr Robert Dove, from whom he purchased his freedom. It was Dr Kearsley who began to train Derham in simple medical and pharmacological procedures. Later, Dr Derham was the first registered African American to practice medicine in the United States (albeit without a medical degree).

It is possible that the painting was done c. 1788 when Dr Benjamin Rush (1746–1813) met Dr Derham in Philadelphia. Dr Rush, an abolitionist, was enthusiastic about the meeting.

‘...the eminent doctor was so impressed that he began a correspondence with Dr Derham that covered many years. The two men exchanged medical information; Rush sent the New Orleans physician his own published writings and received in return informative medical news items. In 1789 Rush read Derham’s paper, “An Account of the Putrid Sore Throat at New Orleans,” before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.’

This publicity surely would have caused public discussion and twitter. This is not to imply the image must have originated the USA, as Dr Derham's career was so exceptional that it surely would have generated wide notice and discussion.

I should also note that there may be an echo of satire in the painting: Dr Rush was widely criticized by his colleagues for continuing to endorse and recommend bloodletting when it had gone out of professional favor.

Ref. Dr James Derham biography...

Google eBooks. ‘Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1’, ‘Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Junius P. Rodriguez’. Editor Junius P. Rodriguez, Edition illustrated, Publisher ABC-CLIO, 2007, ISBN 1851095446, 9781851095445, Length 793 pages, Page 253.

Ref. Dr Rush & Dr Derham's relationship...

"The African American Experience: History of Black Americans From Africa to the Emergence of the Cotton Kingdom" by Philip S. Foner.

http://tinyurl.com/narongr

Engraving of Dr John Kearsley...

http://tinyurl.com/qchh9en

Ref. Portrait of Dr James Derham

http://tinyurl.com/njtjus2

Ref. Biographical summary of Dr Derham

http://tinyurl.com/qx9esds

Collection note:

‘The provenance of the painting provides no clue as to whether it was ever in America.

One question is whether the painting shows a portrait of individual persons or a generic scene. There are comparative British examples of both genres showing black servants/slaves, as can be seen in the volumes entitled ‘The image of the Black in western art’ (by David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., general editors ; Karen C. C. Dalton, associate editor, Menil Collection, 2010).

An example of a portrait: Sotheby's, London, British paintings, 17 July 1985, lot 573; or Christie's, London, Fine English pictures, 2 May 1986, lot 153 (c.1750).

An example of a generic scene, by Dighton, 1784:

http://tinyurl.com/q6uoyjc

Another question would be whether there is an earlier portrait of Kearsley than the 19th-century wood engraving in the New York Public Library.

The face of the surgeon in the painting is well preserved, whereas the lower part of the face of the woman patient had been damaged at some stage and is conjecturally restored.

Best wishes

William Schupbach

Librarian, Iconographic Collections, Wellcome Library’

Completed, Outcome

This discussion is now closed. The title has been amended to 'A Surgeon and His Black Assistant Letting Blood from a Lady's Arm'. It was concluded that this image of bloodletting is a generic, probably purely decorative, scene of the late 1770s or 1780s.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to the discussion. To anyone viewing this discussion for the first time, please see below for all the comments that led to this conclusion.

27 comments

Nice theory, but I think too many planets would have to align. For me, its generic and British. Quite Hogarthian. The naivety of the execution might suggest there's a master version. Could the support (presumably tin) and decorative border suggest a purpose other than a cabinet picture?

I think if an artist was doing a retro scene of the eminent physician in question, it would be for some sort of biographical publication. There are just too many 'generic' pictures from this period with servant/slave boys of African origin.

A generic, decorative, painting probably by a coach painter or similar painter of decorative panels for furniture. English and 1780s seem correct..

The tall narrow hair style and its covering muslin cap, worn by the seated women in this image, (originating from Paris, and common in fashion plates of the period - see attachment- Marchand des Modes dated 1778) dates from around about 1775-8. By 1780s hair styles remained high but grew far wider. If it is a generic scene as seems very likely, then it could of course have been painted in the 1780s by when this narrow high hair style was out of date.

Although the collection reports that the provenance gives no clue as to whether the work was ever in the USA, it would still be useful to know something about the provenance, even if it is just when the Wellcome acquired the painting and from whom (auction sale, etc.?)

Bought by the Wellcome Library on 10 September 1982 from a dealer in Corsham, Wilts., not far from Bath.

But whether it had been in that part of the world for 200 years or two days I do not know.

William Schupbach

Have just heard from the dealer, Michael Wakelin, then of Pickwick, Wilts, now trading as Wakelin and Linfield in Billingshurst, West Sussex. He writes: "Re the painting, which I am sure you have had restored (I hope it came up well),I bought it from a dealer in the West Country but otherwise I have no provenance to offer you. In those days there was a profusion of goods turning up from many different sources and I was lucky enough to come across what was immediately apparent to me to be a fascinating and obviously rare subject. I would of course be very happy to have my name used as a source and I hope what I have said is of some use to you."

Thanks to the Wellcome for following through. While this information does not provide any great breakthrough, it is still important to tap every source possible.

Might this be an illustration of a scene from Samuel Richardson's "Pamela" where she has herself cupped after her baby catches smallpox, in the belief that cupping would reduce the fever in herself if she had caught it from the child ?

There is an interesting image of the painting before restoration on the Wellcome website: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/jq383azt , showing what poor condition it was in when acquired.

Just to clarify, this a scene of blood letting, not cupping, which is something very different, although also believed to be a remedy or therapy for many conditions

There have been no further comments on this painting for over two years, I think we must conclude that this much restored image of blood letting is a generic, probably purely decorative, scene of the late 1770s or 1780s. It has not so far been linked to any artist or doctor, and is unlikley to be without further evidence.

Agree with that conclusion. It raises the question why there was thought to be demand in 18th century England for a painting on metal of a surgeon letting blood, with a decorative border, but that is a different question.

William Schupbach

Thank you both. This long-dormant discussion will close after one week (by 5th March), unless significant new information emerges in the meantime.

As to why such a subject might be wanted: could it have been in some way an advertisement for the services of a doctor or barber-surgeon?

Could I ask the Collection and Art UK to reconsider the headline description of the black assistant as a 'slave'? The artist may or may not have intended him to represent an enslaved person, real or imagined, we just don't know - and if the context is British he probably didn't.

We often read that there was a large and flourishing community of free people of African ancestry living in London and other port cities in the 18th Century; if this is true, then presumably they did their share of reproducing, and there would logically have been plenty of boys available to fill posts as fashionable black pages, grooms and other servants without having to resort to enslavement. We certainly know that some black servants effectively were or had been slaves, particularly in families with West Indian or American estates, but surely it cannot have been all?

Given that, and my strange and archaic attachment to the idea that art and social history should be based on reasoning and evidence, I don't believe that the current title is tenable.

I agree, Osmund. I would suggest "A Surgeon and His Black Assistant Letting Blood from a Lady's Arm."

Though of course the boy may be the lady's page rather then the surgeon's assistant. Indeed that might possibly be the humorous intent of the painting - the doctor has made the incision, but now looks as if he may be on his way out of the door, leaving the boy to handle the blood streaming out of his rather worried-looking patient.

I wonder if a higher-res image might show the boy's facial expression: quiet competence or alarm?

Then I would suggest "A Surgeon and a Black Attendant Letting Blood from a Lady's Arm."

Osmund, thank you for your comments on the title and, Jacinto, for suggesting an alternative. The boy's situation is ambiguous, as you say, and I think Jacinto's second suggestion (an attendant) is a good one. I've attached a detail.

There was inconclusive internal discussion about this very point in connexion with the cataloguing of this work:

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/y7mfkdce/items?langCode=eng&canvas=1

and there are similar subjects with white assistants performing the same or related tasks:

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/v7ejjd6c/images?id=yn7zeyk4 (E Heemskerck)

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/s8tzr6pf/images?id=u34pn6vz (Lambrechts)

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/rp8h6xyh/images?id=gauht83m (Naiveu)

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/jraat8kv/images?id=abhc5ahn (Il barbiere, 1626)

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/crb5e2dt/images?id=ma7g2fbf (caricature)

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/t9gzez5d/images?id=fxa82pft (late 17C French?)

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/fg6jvznp/images?id=ggcwkkag (after B van der Bossche?)

It appears from most of these that the boy works for the surgeon, not for the patient; that presumably means that he is either an apprentice or a son of the surgeon.

Were black boys apprentices?

William Schupbach

... or just a servant. Francis Barber, painted by Reynolds I think, was Dr Johnson's much valued one for many years and they were still being sought as such in the early years of the 19th century.

I fairly recently came across this example in a press advertisement while working on Joseph Glossop (1793-1850), the theatrical manager who completed and opened the 'Old Vic' in 1818, but -as the son of a wax chandler - from 1814 ran a fashionable shop selling candles, lighying oil and 'fashionable lamps' on the corner of Piccadilly and Duke Street, now occupied by Fortnum & Mason:

'Morning Chronicle' 28 January 1822: Wanted, in a small Family, a Young MAN of COLOUR, as FOOTMAN; an East Indian would be preferred. He must be well-looking and of good height, civil, cleanly, active and good-tempered. No servant out of a large family will suit, and an excellent character is indispensible. Apply, from twelve o’clock til four, any day this week, at Mr Glossop’s, wax chandler, 180 Piccadilly, opposite Burlington House.

I expect a trawl through 18th century newspapers would produce other examples but, at least after Lord Mansfield's Somerset judgement of 1772, slavery did not legally exist in England. I suppose one should add 'in theory' given many examples show it still does, often under different terms like 'trafficking'.

Just to clarify that the comment above is to suggest the black boy in the painting is perhaps a (non-slave) servant: with apprentices one has to remember that masters usually required premiums to take them on, which doesn't rule it out but might have made it less likely.

William, whether or not there were black apprentices is not, I think, relevant here: even if he were white he wouldn’t be an apprentice. I think that only one of the boys in the images you link us to (the Lambrechts) might be an apprentice, and he’s not catching blood, he’s holding a bowl of glass cups that the surgeon is applying – just possibly the C17th French one, too, but none of the others. They are just too young. Apprentices in the C18th and earlier were usually around 13 when they began (and later on often 14 and older) – pre-pubescent boys were always extremely rare. The apprentice in art and drama is always essentially a young man, and in paintings any tasks he is shown engaged in tend to be at least semi-skilled; see, for example, the attached Teniers-ish painting of barber-surgeons at work – the apprentice is on the right, apparently preparing some medication. There may actually be an apprentice in your Egbert van Heemskerck painting – but he’s not the boy with the bleeding bowl, he’s the youth preparing something on the table far left (with perhaps another one treating a patient’s foot behind on the right).

The boys are just that – boys, i.e. boy-servants/assistants. The concept is forgotten now, but time was when every tradesman of consequence had a boy or boys of perhaps 8-12 years old sweeping up, holding things steady and/or ready, cleaning tools and work surfaces, and doing other fairly simple tasks, with no formal idea of them learning fully their master’s craft (though some did pick up skills by observation). The apprentice is a much more serious learning position, strictly regulated (and generally paid for): at the end of an apprenticeship the trainee is deemed to be fit to operate in the trade or profession on his own, and to train his own apprentices.

So, I'm afraid that there really is *no* evidence whatever, either in the painting or historically, that the boy is meant to be a slave – and the same applies to the black servant-assistant in your dental print. As already stated, it was fashionable to employ smartly-dressed black boys in all sorts of positions, domestic and not, and Pieter’s ad shows that this extended into the C19th and to older servants like footmen.

Although William has kindly agreed with my conclusion of 25 Feb, I should indeed have commented on the existing title. As Osmund and others have suggested, this which would better read servant, attendant or assistant rather than slave. Much else that remains unknown, such as its function, has not attracted any evidence and must remain speculative. I would only say the that the border, small size and support suggest it was a decorative, domestic painting.

William, would you be happy to conclude with 'A Surgeon and His Assistant Letting Blood from a Lady's Arm'?

Thanks to all for clarifying the subject of this painting. Yes, describing the middle character as the surgeon's assistant does seem the best solution. WS

What I have recently seen aptly described as 'identarianism' - a word which if not already in the Oxford Dictionary probably ought to be - is (like it or not) a general issue of the age, so 'black' would also be best left in for search-term purposes.

Yes, I think Marion may have made a mistake in not retaining 'black' in the title. There was discussion about slave/servant/assistant but black was never in doubt!