Today, the four artists known as the Scottish Colourists, S.J. Peploe, J.D. Fergusson, G.L. Hunter and F.C.B. Cadell, are acknowledged as one of the most talented and distinctive groups in 20th century British art. They emerged as a quartet relatively late in their careers when their Glasgow dealer staged a group show in Paris in 1924 and another the following year in London, turning a loose affiliation of friends bound by common artistic goals into a movement. The group's first show being in Paris was appropriate as their love of France and the influence of the Post-Impressionists and the 'wild beasts' of the Fauves became a defining characteristic of their development as artists.

Enthusers and Beginnings

The story of the colourists begins with the friendship between Peploe and Fergusson, the oldest of the four. Although not meeting until their mid-twenties, they already had much in common. Both had broken free from the constraints of their respectable Edinburgh backgrounds in their determination to become artists, Peploe being the son of a banker and Fergusson the son of a wine merchant. Following their first meeting, they would drop in on each other’s studios, made a painting expedition to the Western Isles and regularly visited France, sharing enthusiasms for contemporary French masters, particularly Manet and Monet. Another key influence was the American James McNeill Whistler, whose brilliance had been fiercely promoted by John Lavery.

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on canvas

H 53 x W 44 cm

Lakeland Arts

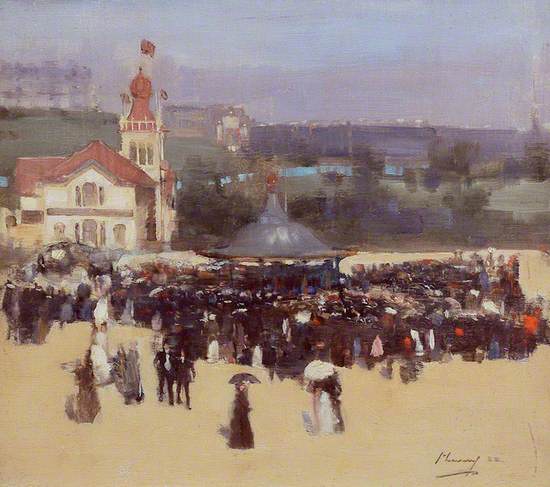

A leading light of the radical Glasgow Boys, Lavery spent the summer of 1888, painting the crowded scenes at the Glasgow International Exhibition. He was following the dictum of his hero, Whistler, that artists can find beauty where the untrained eye does not. He also adopted Whistler’s ability to mass the composition and touch in details with a sable brush in what Lavery termed ‘the spontaneity of attack’. Whistler’s potent aesthetic pervaded not just the art of the Glasgow Boys, but of the upcoming generation of young Colourists led by Peploe and Fergusson.

John Lavery (1856–1941)

Oil on canvas

H 30.5 x W 35.5 cm

The Fleming Collection

Arthur Melville was a generation older than the colourists and although allied to the Glasgow Boys, who broadly speaking can be termed tonal painters relying on gradations of colour to convey a sense of light and depth, he was himself a proto-colourist, using passages of pure colour to convey light and heat. He was also an inspirer, who urged the young Fergusson to leave Scotland for Paris where he too had attended the Académie Julian and taken flight as an artist. He gave the same advice to the sixteen year-old Cadell, being a close friend of the family, who promptly moved to Paris aged 16 with his mother in tow.

Arthur Melville (1855–1904)

Watercolour on paper

H 58.4 x W 76.2 cm

The Fleming Collection

.

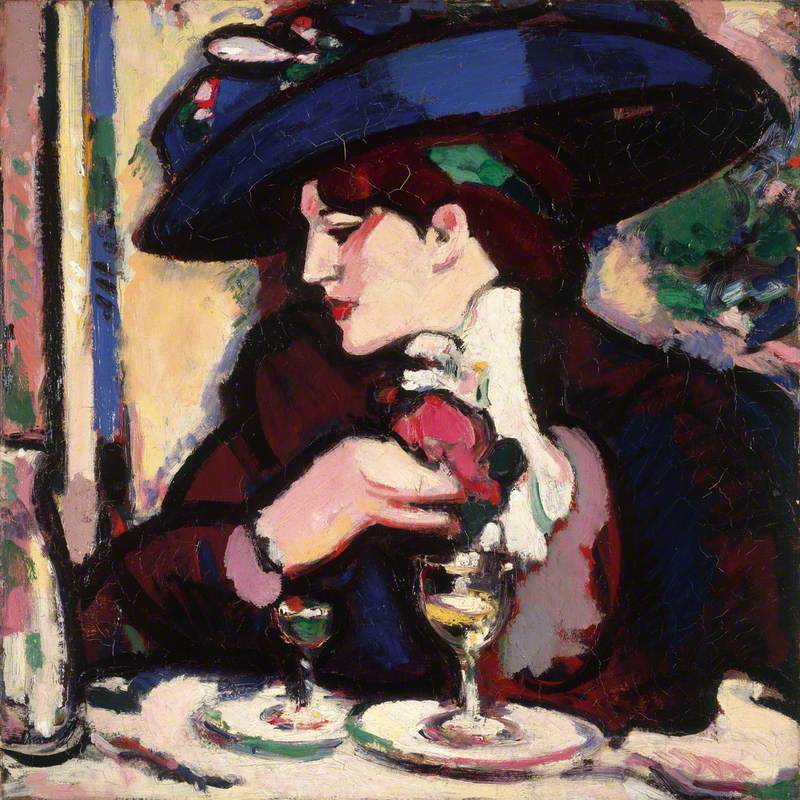

Fergusson’s portrait of his lover and first muse, Jean Maconochie, wrapped in a towering confection of belle epoque millinery, reflects in its dramatic lighting and free brushwork the influence of John Lavery, who in turn had been the disciple of the swagger portraitist, John Singer Sargent as well as Whistler. The shades of past masters – all heroes of the young Fergusson - Eduard Manet, Franz Hals and Diego Velasquez, are also present. The astute critic, Frank Rutter, remarked that ‘the personal force of [Fergusson’s] portraits first thrilled us amidst the rather staid surroundings of the RBA [Royal Society of British Artists].'

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Oil on canvas

H 60.9 x W 50.8 cm

The Fleming Collection

This gritty, roughly painted work marks Peploe out as a signed up member of the Édouard Manet’s awkward squad. Peploe knew Manet’s work well from exhibitions in Paris and through the writings of his champion, George Moore. These still lifes established Peploe’s early reputation. One was acquired by the Scottish Modern Arts Association and was the first to enter a public collection. Flowers in a Silver Jug was acquired by the Edinburgh collector and taste-maker, John Cowan, who was painted by Whistler.

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on panel

H 25.4 x W 34.9 cm

The Fleming Collection

.

Painted at a time when Fergusson and Peploe were almost inseparable as artists and friends, Jonquils and Silver, expresses their shared passion for the dazzling tonal effects pioneered by James McNeill Whistler and Eduard Manet. In the 1905 catalogue of his first solo exhibition, held at the Baillie Gallery in London, Fergusson delivered his manifesto: ‘That he is trying for truth, for reality; through light. That to the realist in painting, light is the mystery; for form and colour which are the painter’s only means of representing life, exist only on account of light.’

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Oil on canvas

H 50.8 x W 45.7 cm

The Fleming Collection

From around 1904, Peploe and Fergusson made annual expeditions to the fashionable resorts on the Normandy coast such as Paris-Plage (now Le Touquet) where they painted on the beach equipped with pochades or small wooden paint boxes which carried panels slotted into the lid, which served as an easel. As time went on these plein air sketches, originally painted in rich creamy tones, became bolder in colour and more vigorously handled in an overtly modern way, suggesting an awakening to contemporary developments in France led by the fauves.

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on board

H 21.5 x W 26.6 cm

The Fleming Collection

In 1905 Peploe moved into a new Edinburgh studio at 32 York Place that had once belonged Henry Raeburn. The walls were painted pale grey with a hint of pink and the floor laid with black linoleum. The light drenched space was the setting for a series of loosely painted figure studies of the model Peggy Macrae in the key of white in homage to Whistler’s female portraits titled symphonies in white which Peploe was able to see at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1902 and again two years later at Whistler’s retrospective in Edinburgh.

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on panel

H 30.4 x W 35.5 cm

The Fleming Collection

.

The Making of the Colourists

In 1905, Henri Matisse, André Derain and Maurice de Vlamink exhibited a group of crudely painted landscapes saturated in colour at the Salon d’Automne. One critic labelled them les fauves – wild beasts. Ever alert to the latest movements across the channel, Peploe and Fergusson began infiltrating bolder colours into their work. The process accelerated with Fergusson’s move to Paris in 1907 followed by Peploe’s in 1910. An intense period of experimentation saw Peploe and Fergusson abandon the rules of ‘realist’ painting in favour of two-dimensional planes of pure colour, often applied directly from the tube, and bold outline with areas of primed canvas showing.

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Oil on board

H 27.2 x W 33.8 cm

The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

.

Fergusson moved to Paris in 1907 exposing himself to the full force of the European avant-garde, led by the ‘wild beasts’ of French art, such as Matisse, Derain and Kees van Dongen, known as the Fauves. An intense period of experimentation followed, which saw him desert the subdued tones of ‘realist’ painting in favour of two-dimensional planes of pure colour and bold outline. The energy and potency of Blue Nude reflects his debt to the expressive black outline as developed by Kees Van Dongen, and to the shameless abandon of Henri Matisse’s fauve masterpiece of 1907, his notorious Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra).

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Gouache on paper (?)

H 30.5 x W 24.8 cm

The Fleming Collection

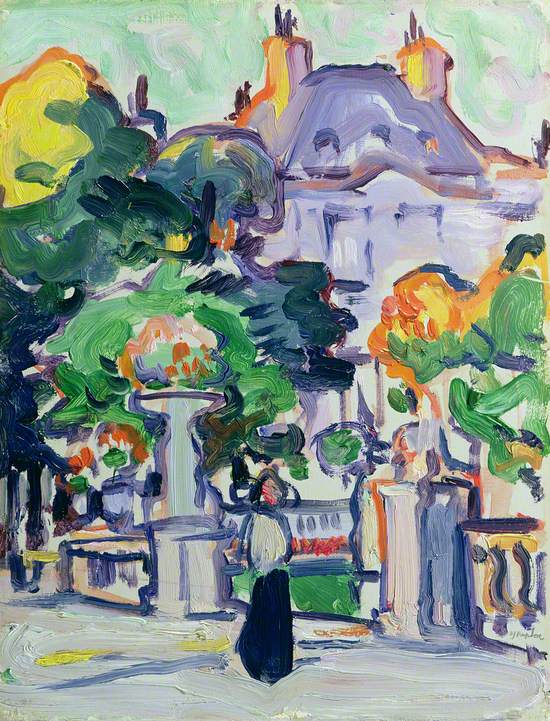

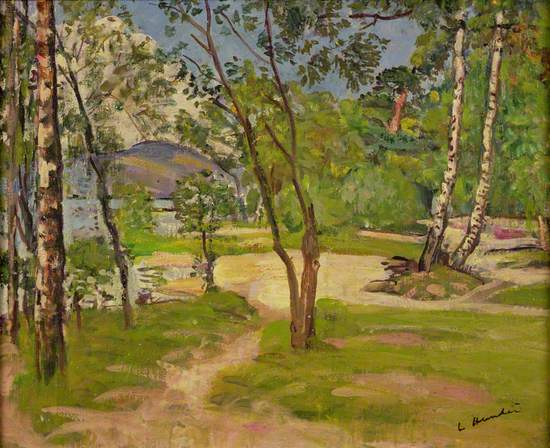

Peploe’s move to France in 1910 was a turning point. Over the previous five years, his annual visits had brought him into contact with the fauves and with the continuing reassessment of the emerging giant of modern art, Vincent van Gogh. Luxembourg Gardens reveals his surrender to the currents of the zeitgeist: to the raw expressionism of the fauves and to the vivid palette and technical accomplishment of Van Gogh. A simplified graphic version appeared in the avant-garde journal Rhythm, of which Fergusson was editor, identifying Peploe with the rhythmist group who perceived: ‘the essential forms, the essential harmonies of line and colour, the essential music of the world.’

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on wood panel

H 35.6 x W 27.9 cm

The Fleming Collection

A Rising Star: F.C.B Cadell

In 1898 Cadell left Edinburgh aged 16 to attend art school in Paris where he stayed on and off until 1905. His early exposure to the Impressionists underlies the technical freedom of his early work, but so too does the impact of Manet and Whistler, playing on their absorption with the pictorial effects of black and white. His swagger portraits of elegant women in his New Town studio were a contemporary take on the fashionable portraiture of the Glasgow Boys such as Lavery (with whom he exhibited); and were a great commercial success.

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Oil on millboard

H 45.7 x W 35.5 cm

The Fleming Collection

This fresh and airy watercolour conveys the exquisite interior of Cadell’s pre-war George Street studio. It also suggest Cadell’s swaggering approach to his art which he summed up in his praise of Whistler’s 1890s persona of the artist-dandy: ‘…he had what some great painters have, a certain ‘amateurishness’ [as in] a gentleman painting for his amusement.’

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Watercolour on paper

H 60 x W 67 cm

The Fleming Collection

In 1909 Cadell moved into his first studio at 130 George Street, which he decorated like Peploe’s (whom he had met that year) in pale shades of white, grey and lilac, with black floorboards polished to a sheen. This was the backdrop for a series of interiors inspired by Manet and Whistler, whom the latter he described as ‘the most exquisite of the ‘moderns’. Cadell often included his own paintings in the composition, which in this case appears to be an Iona seascape marking his first visit to the island in the previous year, which began a life-long passion for the place.

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Oil on canvas

H 76 x W 63.5 cm

The Fleming Collection

1913, oil on canvas by Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

War Work

The youngest of the group by almost ten years, Cadell was the only colourist to fight in WWI, volunteering immediately after the delaration but only pronounced fit in 1915. Peploe, aged 43, was called up for service only to be disqualified on medical grounds. Back in his studio, he continued to work in the fauve manner despite his Edinburgh dealer refusing to show his 'new, raucous, exuberant kind of painting.'

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on canvas

H 80 x W 62.2 cm

University of Hull Art Collection

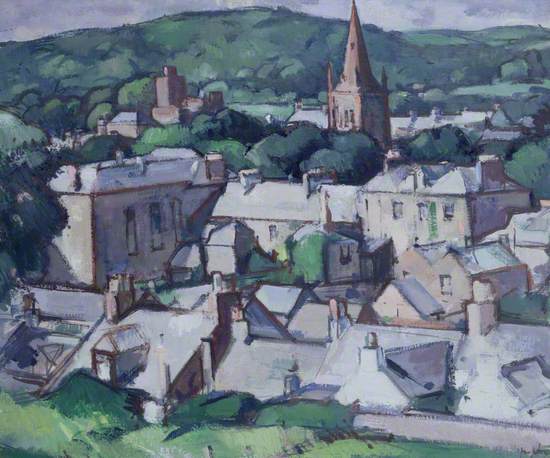

During the war years, Peploe sought a new artistic challenge. ‘I am finished with the colour block system’ he wrote to Cadell ‘…and await a new development …one just keeps going like a machine…I have to paint.’ In 1915, he made the first of a number of visits to Kirkcudbright, home of his close friends from his Paris days, the artists, E A Taylor and Jessie M King. His paintings of the picturesque town emphasise the geometry of its architecture revealing the presiding influence of Cezanne in his analysis of form, colour and tone.

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on canvas

H 53.3 x W 63.5 cm

The Fleming Collection

.

Pre-occupied with the dance school run by his partner, the choreographer, Margaret Morris, Fergusson's limited wartime output produced a handful of powerful images of destroyers and submarines based in Porthsmouth Royal Naval Docks. Imbued with the spirit of the age, he drew on the geometry and hard-edges of the futurist and vorticist painters, such as Wyndham Lewis. Fergusson's 'Three Submarines' also owes a debt to Charles Nevinson, a vorticist in all but name.

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Oil on board

H 28 x W 35 cm

Perth & Kinross Council

The Fourth Man Revealed

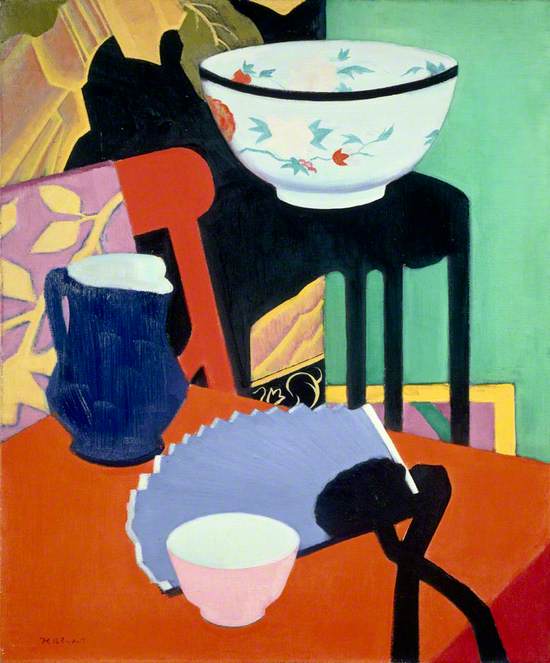

Hunter’s formative life was spent in California where, aged fifteen, he had emigrated with his family. A passionate draughtsman despite no formal training, he developed into an accomplished illustrator for leading publications in San Francisco. Fired by a trip to Europe in 1904, he determined to break free of illustration to become a painter. His ambitions turned to ashes when all his major new work was destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake on the eve of his first solo exhibition. Aged 29, he retreated to Glasgow to rebuild his life as an artist. His virtuosity coupled with a keen study of old Dutch and modern French masters resulted in a series of luscious still lives, catching the eye of the influential dealer, Alexander Reid.

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Oil on canvas

H 51.1 x W 61.3 cm

Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)

Hunter spent the last two years of WW1 working on his cousin’s farm in Lanarkshire. It was also a time of intense study and experimentation in his art as he wrestled with the theories of Van Gogh, Cezanne and Gauguin. His discovery of the Fife landscape and shoreline inspired a series of plein air sketches, which proved a turning point in his development. He described having ‘smashed through to something, forward in strength and simplicity and backward in refinement…’ as exemplified in this vibrant sketch of the fishing village of Lower Largo.

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Oil on millboard

H 20.3 x W 51.4 cm

The Fleming Collection

Hunter’s discovery of the Fife countryside in 1919 proved a major source of inspiration over the next few years. His sense of colour responded to the opportunities of the red tiled roofs of villages such as Ceres, but so too did his draughtsman’s love of outline revealing one of his instinctive traits as an artist, although often suppressed. ‘I hate this hugging of colour. ‘ He wrote in 1923. ‘I feel it will be said yet that my sense of line is greater than my sense of colour, and I’ve hardly used it.’

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Oil on canvas

H 60.9 x W 50.8 cm

The Fleming Collection

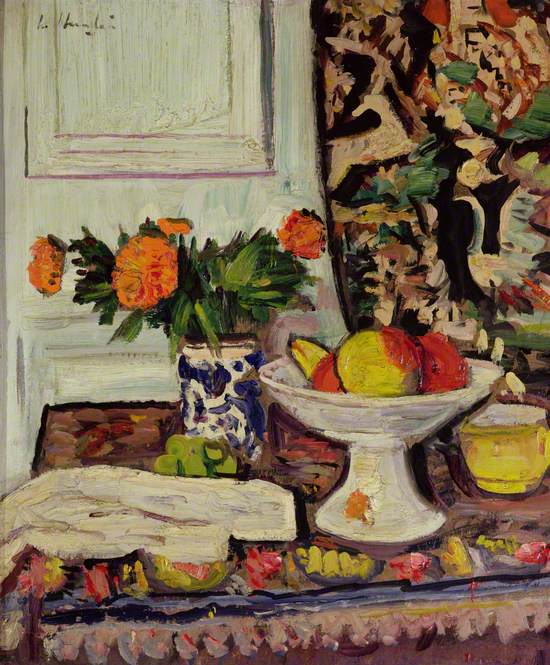

In the early 20’s Hunter pushed the boundaries of still life painting in a relentless examination of the balance between colour, line and form as interpreted by Cezanne and increasingly by Matisse. Peonies reveals his debt to Matisse in the decorative elements but also one of his prized dicta of Cezanne’s that ‘when colour attains its richness, form attains its plenitude.’ When the cheerleader for Post-Impressionism, Clive Bell, saw this painting at a show in London, he wrote: ‘This is the finest picture in this exhibition and I do not know who painted it’.

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Oil on board

H 61 x W 50.8 cm

The Fleming Collection

The Quartet Assembles

The outbreak of peace saw the emergence of the Colourists as a quartet. Peploe had already predicted of his close friend Cadell that after three years in the trenches: ‘…you will absolutely give up flake white’. The two collaborated on developing a bravura approach to colour whilst sharing props for elaborate compositions of still lifes and interiors with dazzling brio. Meanwhile Hunter’s war years of intense study and experimentation resulted in his breakthrough as an artist in 1919 with a series of Fife landscapes, which launched him as a radical colourist painter. Fergusson took up where he had left off in 1914 spending long periods in France. A growing influence of Cézanne pervades his post-war paintings which have a quieter mood.

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Oil on canvas

H 61 x W 50.5 cm

National Galleries of Scotland

.

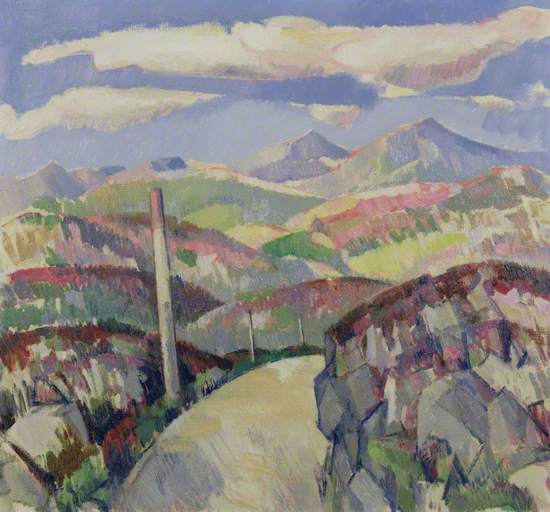

Unlike his fellow colourists, Fergusson had spent little time painting in Scotland following his move to Paris in 1907. However, he made a tour of the Highlands in 1922 and 1928 and staged two exhibitions of the works. His output revealed a growing interest in Cezanne fused with the restless machine aesthetic of Vorticism which he had deployed in a series of paintings of Destroyers at the Royal Navy Docks, Portsmouth. A distant echo of his Rhythm paintings resonates. The Highland series comprised his first solo show in Scotland, staged in Edinburgh and Glasgow in 1923.

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Oil on canvas

H 54.5 x W 59.5 cm

The Fleming Collection

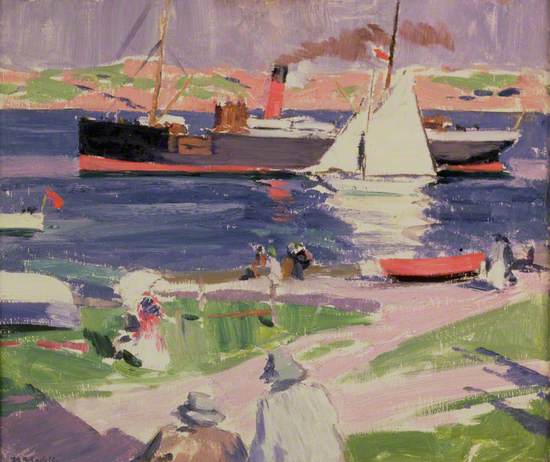

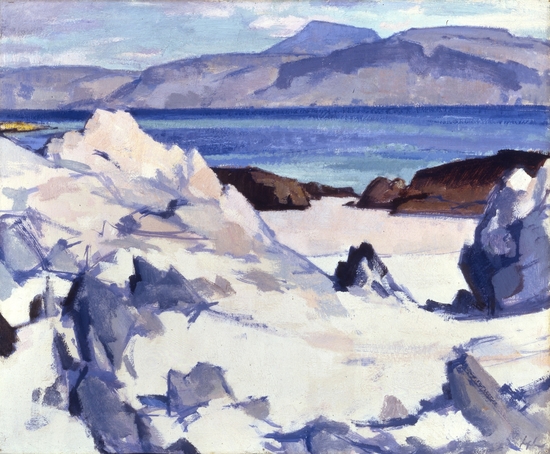

With the encouragement of Peploe, Cadell abandoned his pre-war style in favour of colour, which was used to brilliant effect on his annual painting trips to Iona. Priming his canvasses with an absorbent white mix, known as gesso, he captured the intense colours from the light refracted off the sea. In order not to weaken the luminous effect, each painting came with an instruction on the back in his elegant hand: Absorbent ground. NEVER varnish. The Dunara Castle was the first steamer to make regular trips to Iona.

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Oil on millboard

H 38.1 x W 45.7 cm

The Fleming Collection

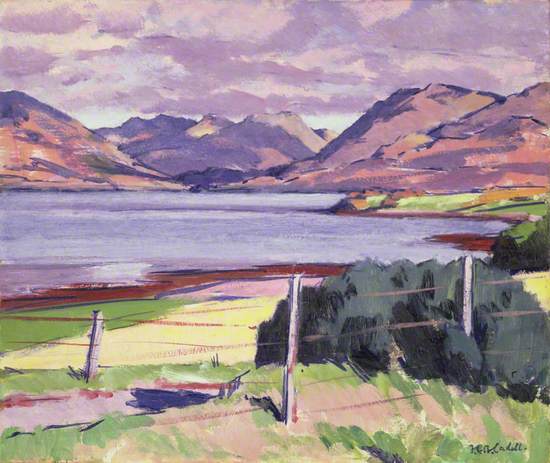

Cadell’s depiction of unadorned nature reveals both his mastery of colour - as in the shoreline caught by sunlight – and of tone - as in the effects of light across the water and hills to create a sense of distance.

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Oil on board

H 37.5 x W 45.1 cm

The Fleming Collection

Hunter first visited Loch Lomond in 1924 where the colourful houseboats inspired a series of works in homage to Matisse. He returned in 1931 to spend the summer on a houseboat with his young girlfriend, Marnie Scrafton. She described him as ‘a gay laughing bohemian with a wonderful knowledge of the world.’ His happiness produced a harvest of luminous paintings that distil the lessons of his lifelong search for the balance of colour, light and form. He died a few months after leaving Loch Lomond in December 1934, aged 54.

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Oil on canvas

H 45.7 x W 55.8 cm

The Fleming Collection

In August 1918, Peploe wrote to Cadell: ‘When the war is over I shall go to the Hebrides, recover some virtues I have lost. …Oh, Iona. We must all go together.’ Cadell had first visited the island in 1912 and in 1920 he took Peploe and they returned virtually every summer until the former’s death in 1935. Peploe fixated on the north end of the island with its views to Mull, repeatedly capturing the ‘visions of rare beauty’ produced by the forever changing weather and light.

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

Oil on canvas

H 50.8 x W 60.9 cm

The Fleming Collection

.

Fergusson had been drawn to sculpture from the early 1900s when he viewed the Benin bronzes shown in Edinburgh. His Paris notebooks also reveal an early interest in Cambodian and Indian carvings. He modelled his first figures in Paris before WW1 influenced by the avant-garde ‘primitivist’ sculptors Jacob Epstein and Henri Gaudier –Brzeska, whom he knew. Eástre, Saxon goddess of Spring, was inspired by his partner, Margaret Morris, who choreographed a ballet of the same title. His golden brass orb, composed of spheres and hemispheres, was he wrote the ‘effect of the sun [and its] triumph…after the gloom of winter.’

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961) (posthumous cast)

Brass

H 42 x W 20 x D 16 cm

The Fleming Collection