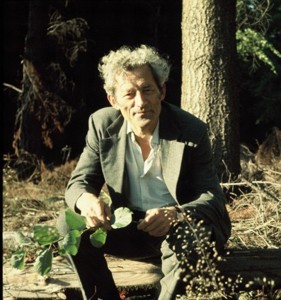

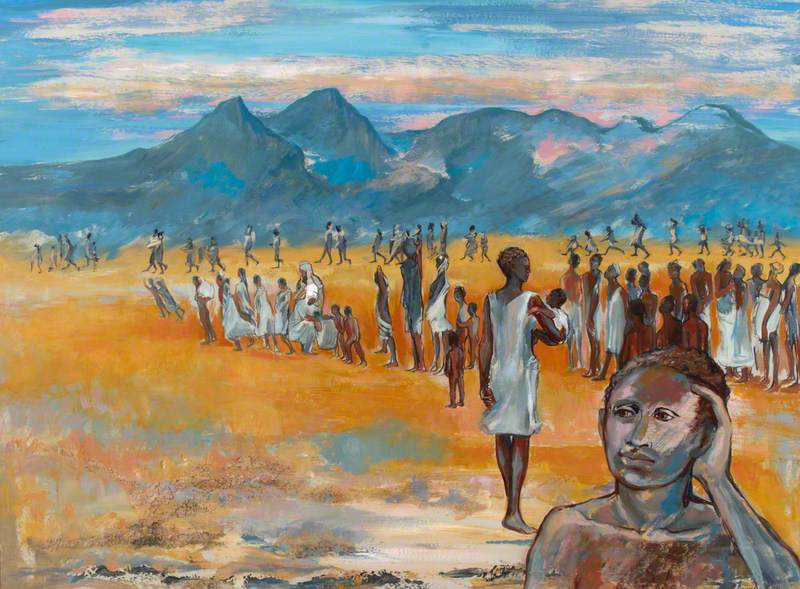

Albert Reuss (1889–1975) was a Jewish painter and sculptor who developed a uniquely individual style. Born in Vienna, he fled to England in 1938 following Hitler’s annexation of Austria. In the process, Reuss lost many members of his family, and the reputation he had built up as an artist in Vienna. He continued to work as an exiled artist in England, but his style changed dramatically, reflecting the trauma he had suffered.

I became aware of Reuss’s work at an exhibition of Cornish artists in November 2015 held at Penlee House Gallery and Museum, Penzance. Little was known of this neglected artist, so I was determined to find out more about the life and work of this intriguing man; I interviewed many people who knew him and retrieved a huge archive from Vienna, which included much of Reuss’s lifetime correspondence. A fascinating story emerged, full of human drama and tragedy, and of the lonely and isolated artist's struggle to develop his art and to survive, all set against the background of world historic events. The recovered correspondence included first-hand accounts of Reuss’s escape from Vienna with his wife Rosa, and of their experience as refugees in wartime Britain.

But this was the time of the rise of Hitler and the Nazi regime, and by 1938 it became clear that Albert and Rosa would have to flee their home country.

Reuss was the son of Ignaz, a Fleischhauermeister (master butcher), and Sidonia Reisz. Originally from Hungary, where their first three sons were born, the family moved to Vienna in the late 1880s, where Albert was born, followed by a further six children, sadly three of whom died in infancy. From a young age, Albert became estranged from his family; a frail, sickly and vulnerable child, he seemed neither to fit into nor to belong to the family into which he was born.

He was introduced to the world of art by a rich uncle, who appears to have instilled in the young boy a life-long inferiority complex. His artistic abilities emerged at an early age, but unable to pursue his dream of becoming an artist, he was obliged, on leaving school, to assist his father as a butcher. Given his delicate disposition and artistic sensibilities, butchery was hardly an appropriate choice of profession. There followed a series of equally unsuitable jobs, including salesman, childminder

In 1915 he met his future wife, Rosa Feinstein, who offered him the acceptance he so desperately needed. In that year, she wrote to him:

'This is the right day for me to assure you, again, of my deepest love. Come what may – your Röslein will always be with you.'

There can be few expressions of undying love and support made at the beginning of a relationship, which can be shown to have been fulfilled 55 years later. She was his life-long companion, the person who encouraged him in the face of all difficulties, and perhaps most importantly of all, the buffer between him and the world he found so perplexing.

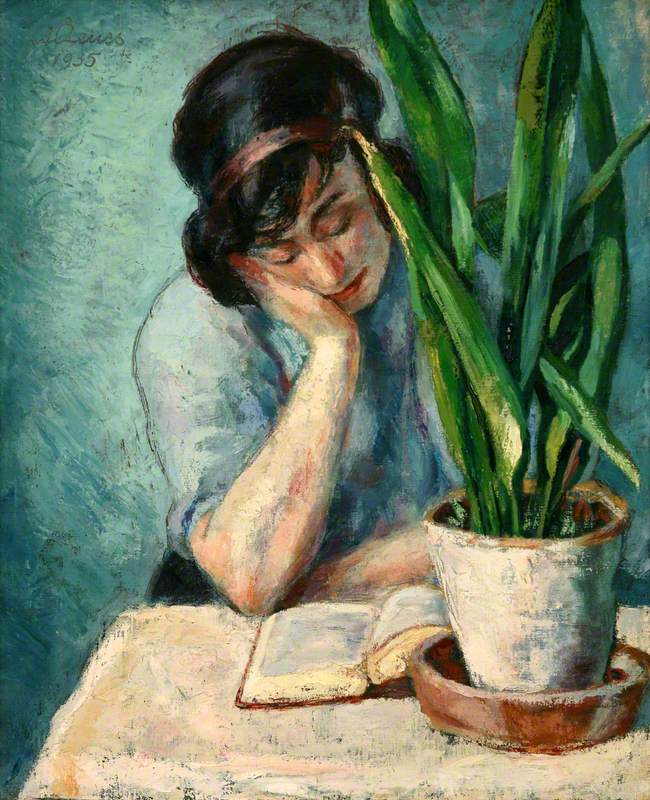

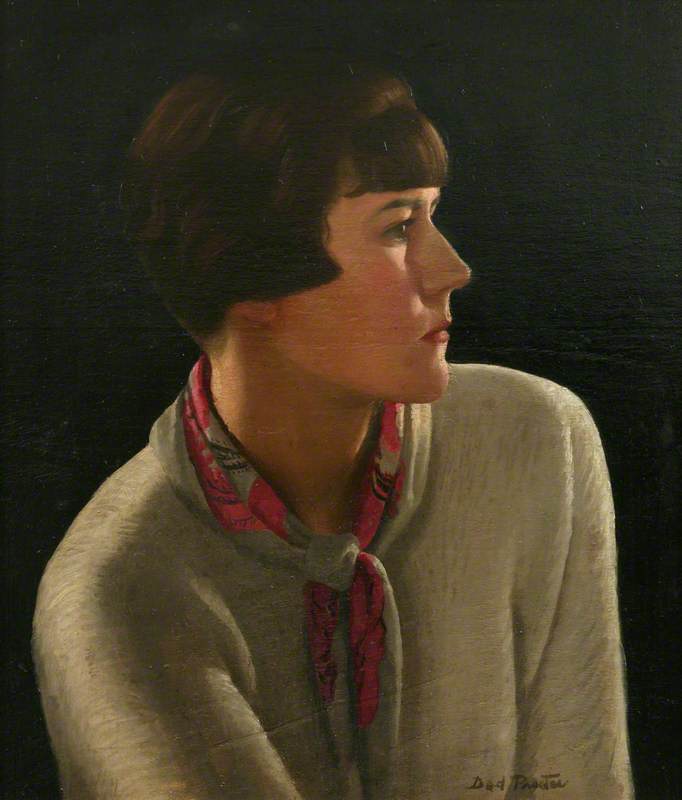

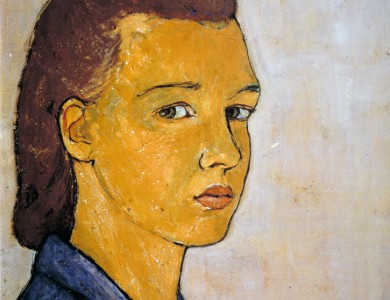

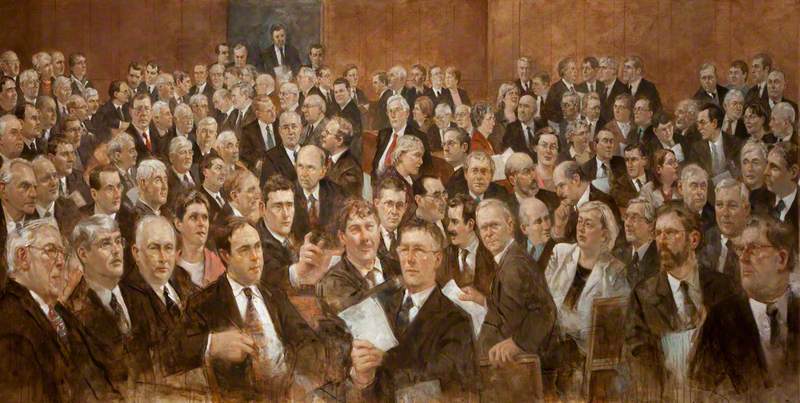

During the 1920s, Reuss gradually established himself as an artist, working initially in portraiture, then developing an individual style of line drawing. In 1930, a newspaper proprietor sponsored him to spend a year in Cannes, where he worked on portraits and landscapes in oil. He subsequently became a member of the prestigious artists' association, the Hagenbund, with whom he exhibited on a number of occasions. The couple filled their flat in Vienna with numerous books,

Nevertheless, Reuss held numerous solo exhibitions in municipal galleries throughout England, particularly in Cornwall, Cheltenham

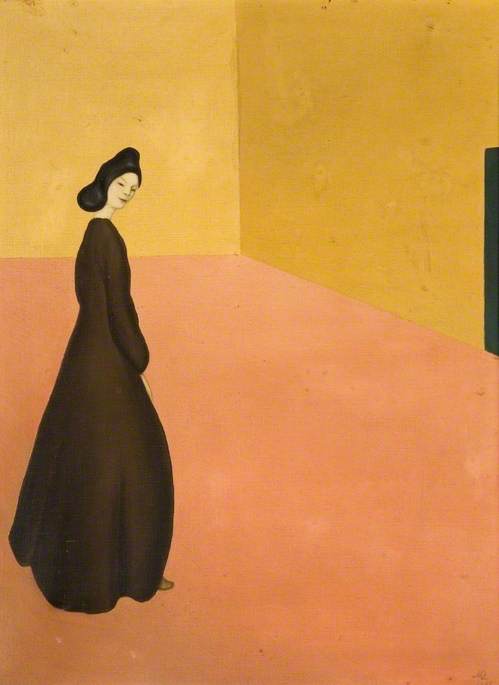

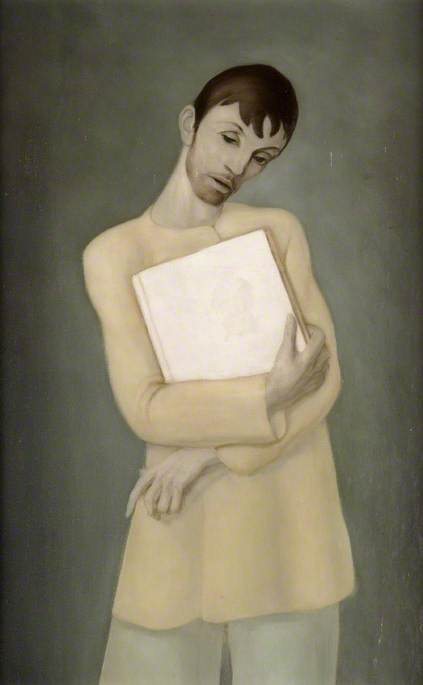

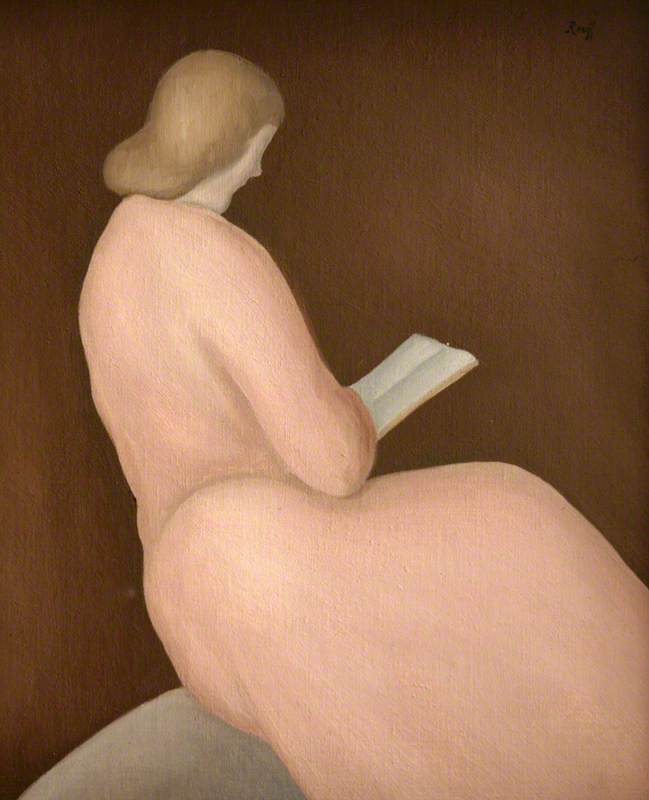

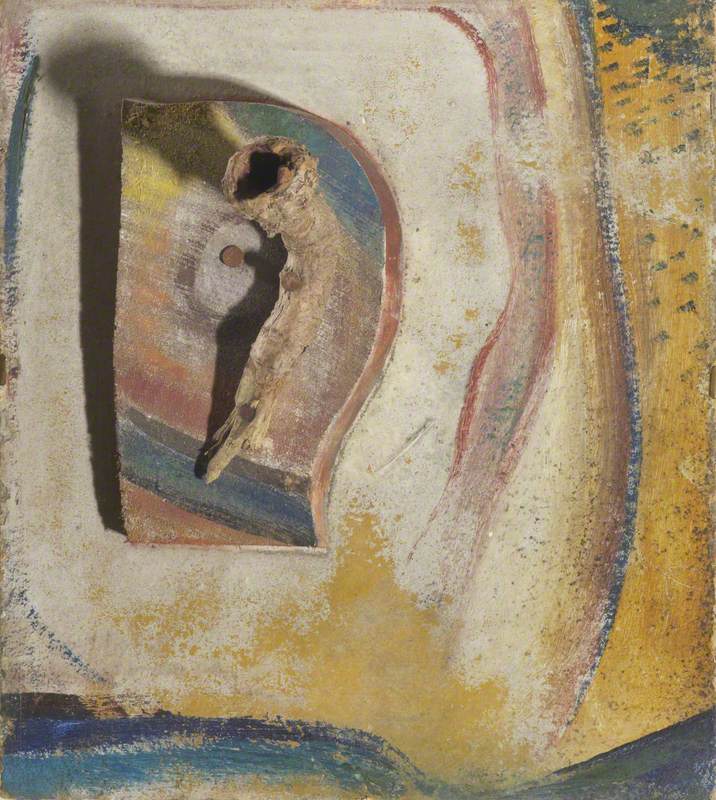

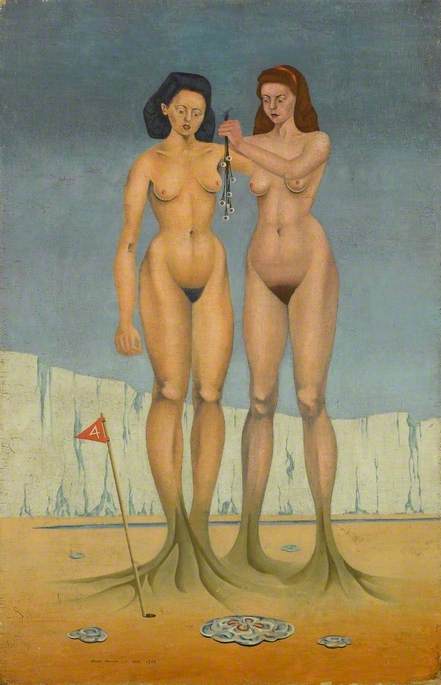

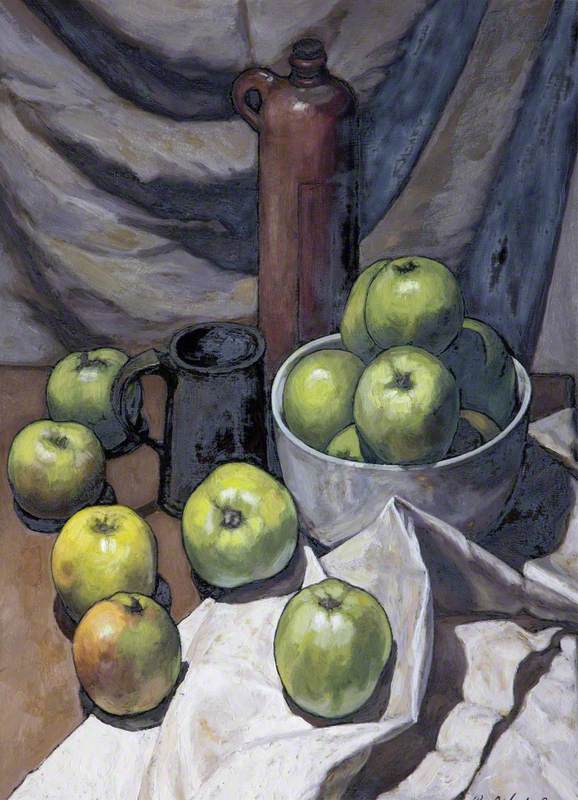

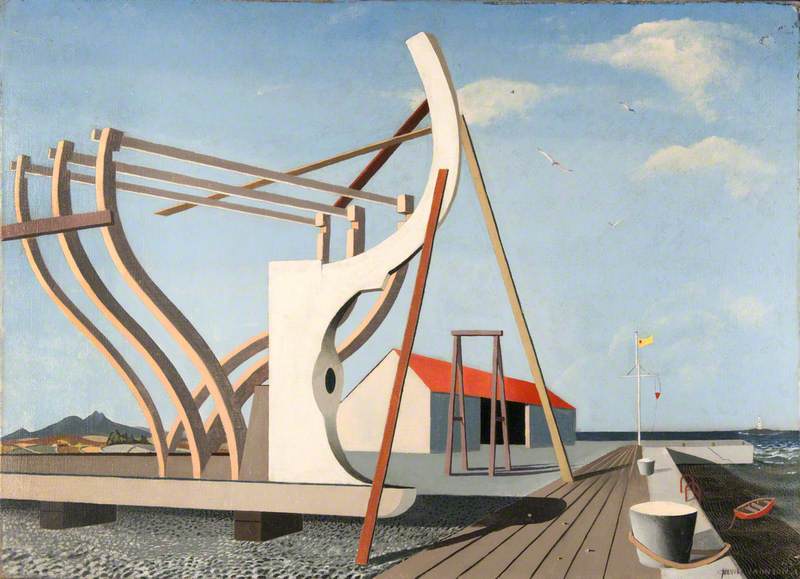

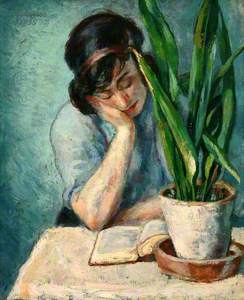

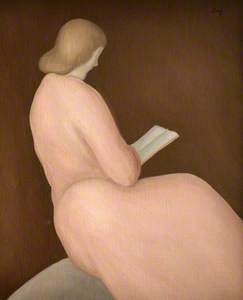

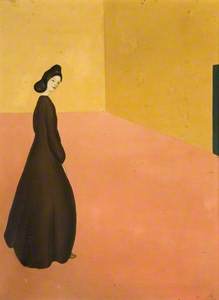

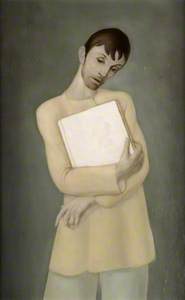

Following his exile, there was an immediate change in Reuss's work; whereas his oil paintings in Vienna were

The Kuntshandel Widder Gallery has provided an apt description of Reuss’s post-Vienna work:

'Reuss’s artistic output is very much informed by his biography. Objects, floating relinquished through space and having lost any foothold,

Reuss was a complex individual. A tall, slim, handsome man, he could often appear aloof, even arrogant. Despite his Viennese elegance, he sometimes behaved irrationally, for example, he wrote a number of highly inappropriate letters to the very people who were trying to help him. Yet despite his eccentricities, and at times his unacceptable

Several provincial galleries hold his work, most notably Newlyn Art Gallery in Cornwall, as do the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Belvedere Gallery and the Albertina in Vienna, and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in Israel.

Susan Soyinka, author of Albert Reuss in Mousehole: The Artist as Refugee, published by Sansom & Co.

The exhibition 'Albert Reuss' was at Newlyn Art Gallery from 23rd September to 7th October 2017.

The text of this page is available for modification and reuse under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-