Download and subscribe on iTunes, Stitcher or TuneIn

Art Matters is the podcast that brings together pop culture and art history, hosted by Ferren Gipson.

Series four of Britain's Lost Masterpieces has just finished airing on BBC Four – did you catch it? I'll warn you now that if you haven't seen it yet and you plan on watching, you may want to stop reading because spoilers lay ahead...

I recently sat down again with Bendor Grosvenor – one half of the show's dynamic hosting duo, which includes social historian Emma Dabiri – to discuss the latest series of Britain's Lost Masterpieces and get Bendor's thoughts on the amazing discoveries and transformations that take place. Before any filming starts, Bendor undergoes a lengthy process of combing the Art UK site to find paintings with unknown artists or equally mysterious attributions. After settling on a long list of images, he sets off – torch in hand – to view the artworks in person and narrow the list down to the most promising pieces.

'The basic pattern of connoisseurship is that you recognise a composition or artistic technique,' says Bendor. 'It's quite difficult to describe because it's just a little flicker of something – a gut instinct, a sense of recognition – in the same way that someone might recognise a friend on the street.'

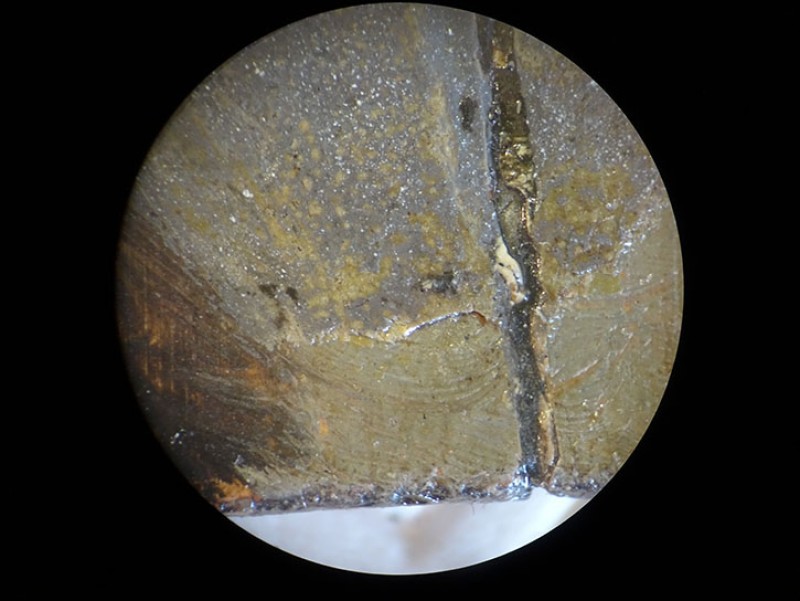

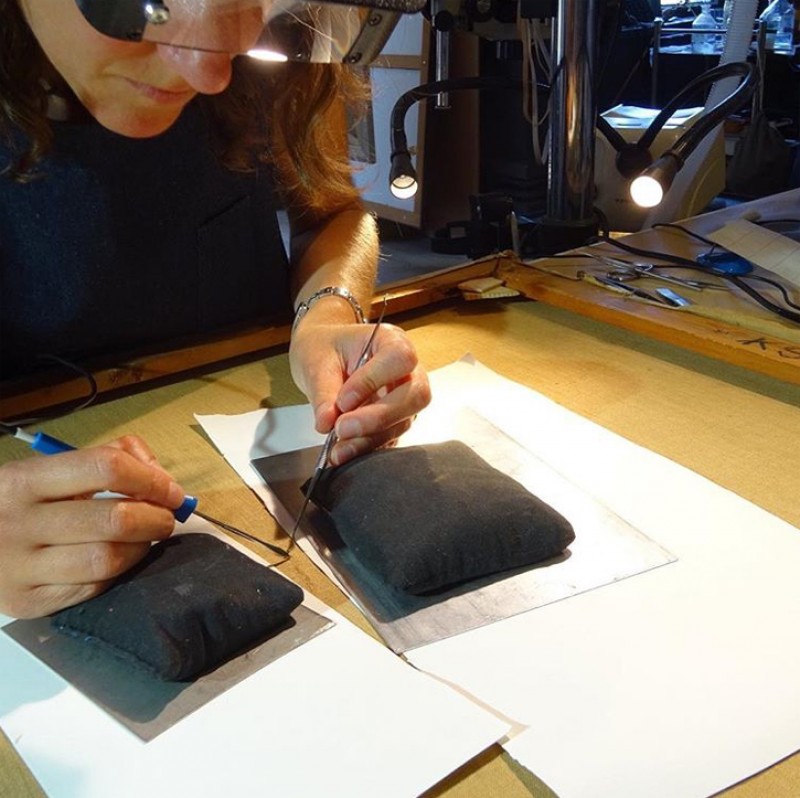

Once that flicker turns to a flame, the next step is to send a painting to a restorer – in the case of this series, that's Simon Gillespie. Cleaning is an essential first step because restoration can help remove decades of grime and old varnish that has led to a downgrade in attribution. Sometimes a work may have been poorly cared for or restored, which can make it difficult to get an accurate view of the masterpiece hiding beneath. This was the case for Autumn, a painting in episode two of the series that had a remarkable transformation. The painting was initially split into two halves and was largely overpainted in the middle. Bendor says the rendering of the cows' signature backsides in the painting were a telltale that the piece could be by Jan Brueghel the elder.

A Wooded Landscape, Autumn Evening

(copy of Thomas Gainsborough)

Thomas Barker (1769–1847)

Sometimes cleaning leads to an exciting attribution, as was the case with the Brueghel and Botticelli paintings featured in this series, but it can also confirm that a painting is, in fact, a copy. After some investigation, A Wooded Landscape, Autumn Evening was attributed to Thomas Barker, who was a skilled copyist of Old Masters.

In the course of investigating the potential Gainsborough, Bendor visited The Holburne Museum to see a family portrait of the Byam family. They offer an example of why Gainsborough dreaded doing portrait work and called it the 'cursed face business'. George Byam commissioned this portrait in 1762 to celebrate his marriage, and later asked Gainsborough to add a portrait of their daughter and to repaint the fashions depicted.

'We often assume that portraits like this were designed to record people deliberately for posterity ... but in fact, they were usually statements of wealth,' says Bendor. 'Because fashions changed as quickly as it does today, you would sometimes risk looking a bit old-fashioned if you had your friends around and had your picture on the wall in last season's clothes.'

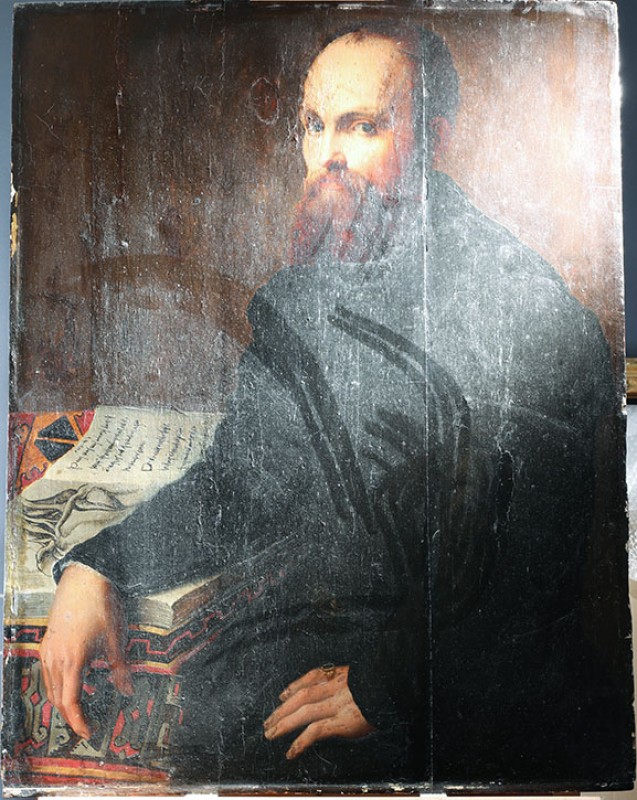

George Oakley Aldrich (1721–1797)

c.1750

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) (attributed to)

Speaking of fashion, the rendering of a fur in a painting of George Oakley Aldrich served as an interesting clue to the painter of a portrait found in the collection of the Bodleian Libraries. The painting has now been attributed to Pompeo Batoni, and is believed to be one of his early Grand Tour portraits, which were highly sought-after.

'The Grand Tour was in the eighteenth century when there was a period of relative peace on the continent, and increasing prosperity amongst British upper classes,' says Bendor. 'They all decided to go and have an extended gap year, so to speak, in Italy, and learn about art and culture. It was also an opportunity to be debauched.'

Virgin and Child with a Pomegranate

c.1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510) (studio of)

Meanwhile, investigation of the painting eventually attributed to Botticelli's studio led to an interesting side discussion about how our tastes in beauty can bias our judgement. 'That's one of the risks of connoisseurship,' says Bendor. 'It is about inexplicable neurological connections between your brain and your eye – and sometimes your gut. It is obviously prone to be infected, if that's the right word, by all manner of assumptions and preconceptions.'

While we have to be mindful of potential bias, our personal tastes are often a starting point for the things we learn more about, and harnessing those interests can make a great foundation for exploring art history. On the back of the Association for Art History's announcement of a new online art history A Level, I asked Bendor if he had any advice for budding art historians.

'Remember that [art history] is not only a discipline that you learn from books, perhaps images online and, importantly, words. It's about going out to museums and almost emptying your head of all preconceptions and just looking at the pictures,' says Bendor. 'You have to do all that to train your eye – and I'm afraid it does take a long time – so that you can really understand everything that's going on in a painting.'

Be sure to listen to the full conversation with Bendor via the player or links at the top of this story, and catch up on all three episodes of Britain's Lost Masterpieces on BBC iPlayer.

Listen to our other Art Matters podcast episodes

.jpg)