Published in October 2018 in France, Mona Chollet’s new book Sorcières: La puissance

In the past decade, the revival of the witch has subsumed an important faction of cultural, spiritual and political conversations, becoming a fashion phenomenon as much as a symbol for gender politics in the twenty-first century. However, this revival has predominantly centred on an image of the witch that was more palatable, more desirable, and above all, more consumable: a young woman. Recent releases include the return of Archie Comics character Sabrina Spellman to the small screen in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. With the titular character played by 19-year-old Kiernan Shipka, the series acts as a fitting summary of who the witch is in contemporary culture: she is a young woman, cis-gendered and white, and is often either in a heterosexual relationship or the object of heterosexual desire. When the witch is presented as an adult woman, she is seldom over 50, with for sole justification of this eternal youthfulness that witches have the power to halt the ageing process.

Yet this framing of the witch, as eternally young and desirable to the male gaze, both in her physique and attitudes, is at odds with the political realities of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European witch-hunts.

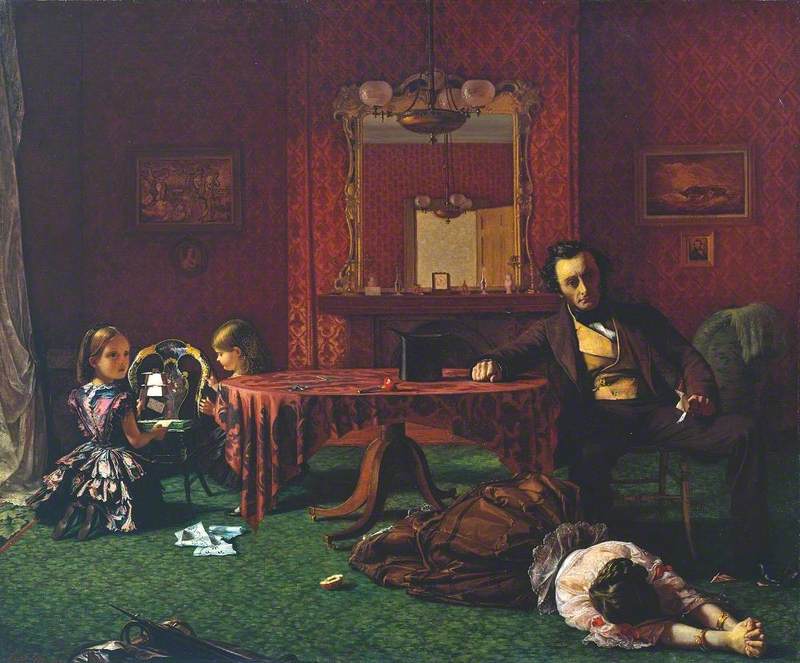

An Arrest for Witchcraft in the Olden Time

1866

John Pettie (1839–1893)

This is where Doctor Who’s eighth episode The Witchfinders comes in as a novel portrayal of witchcraft in popular culture. In the episode, the Doctor (Jodie Whittaker) and her companions arrive in rural England in the seventeenth century, to find a small village torn apart by witch trials. The first execution they witness is that of an old woman, the grandmother of a character named Willa, whom we quickly learn lost her mother to the trials. In keeping with historical accuracy, the old woman was the village’s healer. In the introduction to her book, Chollet reminds the viewer of the historical realities of the European witch-hunts, noting that elderly women were most often the first targets when suspicions of witchcraft arose.

Peasants Fleeing (Witchcraft)

c.1640

Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne (1589–1662)

The case of Willa’s grandmother in Doctor Who’s The Witchfinders is thus far from anecdotal. Chollet notes that several bloodlines of women were killed during the witch-hunts, as witchcraft was believed to be hereditary. The possession of medical knowledge was also a determining factor in accusations, and the usual targets of the hunts were village healers, who often acted as the community’s midwife.

Thomasine Blight (1793–1856), the White Witch of Helston

1856

William Jones Chapman (1808–after 1870)

With this medical knowledge being passed

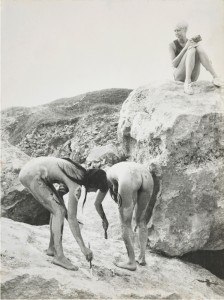

A witch riding backwards on a goat, with four putti carrying an alchemist's pot, a thorn apple plant

c.1500, engraving by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

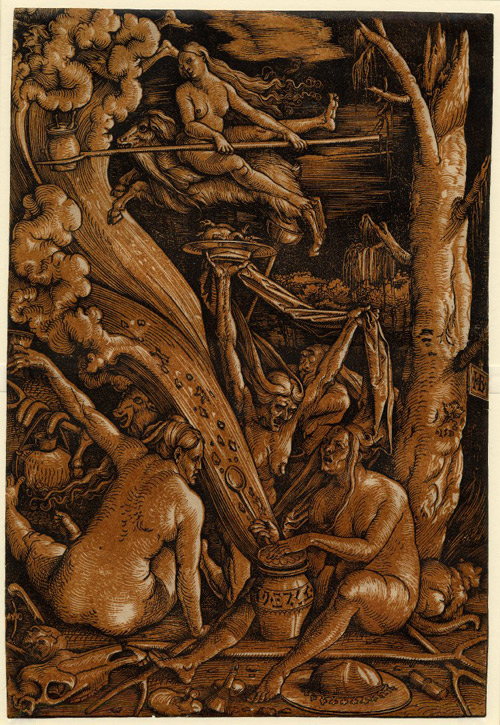

This image of the elderly witch as the 'hag' is one that was particularly prevalent in the early modern popular thought

The Witches' Sabbath

1510, colour woodcut from two blocks, tone block orange-brown by Hans Baldung (1484/1485–1545)

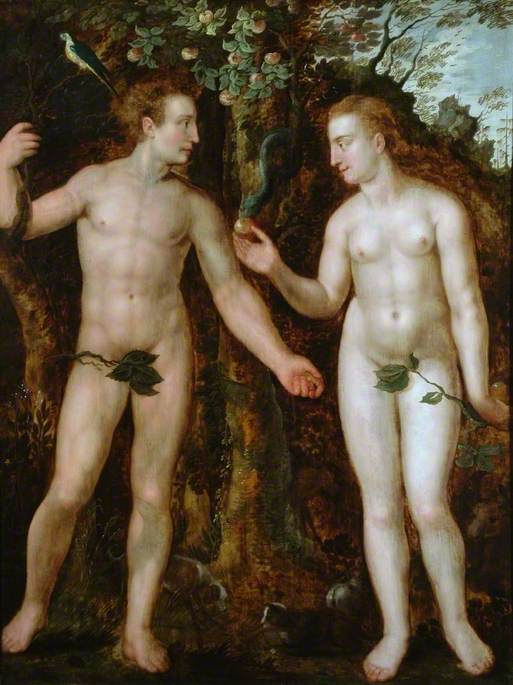

Canonical sixteenth-century examples include Albrecht Durer’s famous engraving of a witch riding backwards on a goat (c.1500) and Hans Baldung's The Witches' Sabbath (1510).

Macbeth and Banquo Meet the Three Witches on a Heath; Scene from Shakespeare's 'Macbeth'

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825) (after)

In his 1606 tragedy Macbeth, Shakespeare introduces the Three Witches (or Weird Sisters), which were to inspire artists across Europe in the following centuries. In particular, famed Shakespearean painter Henry Fuseli produced many representations of the witches. In Macbeth and Banquo meet the Three Witches..., Fuseli shows the scene in which Macbeth meets the witches for the first time, and hears the prophecy that will set off the series of dramatic events central to the famed tragedy. The Three Witches are represented as old women, with heavily wrinkled faces and crooked noses; their bodies are dressed in large robes, with long white hair blending into the fabric so they become indistinguishable. The women hold their hands toward the two characters standing opposite them, in a perfectly coordinated line, their backs crouched to emphasise both their old age and their villainous natures. This depiction of the three witches is reminiscent of Chollet’s observation on the popular imagination’s idea of the old woman as repulsive and ill-intended.

'Macbeth', Act I, Scene 3, the Weird Sisters

c.1783

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

Fuseli furthers this negative representation in his painting 'Macbeth', Act I, Scene 3, the Weird Sisters, where the three witches are shown in the same position previously observed, but this time shown in a

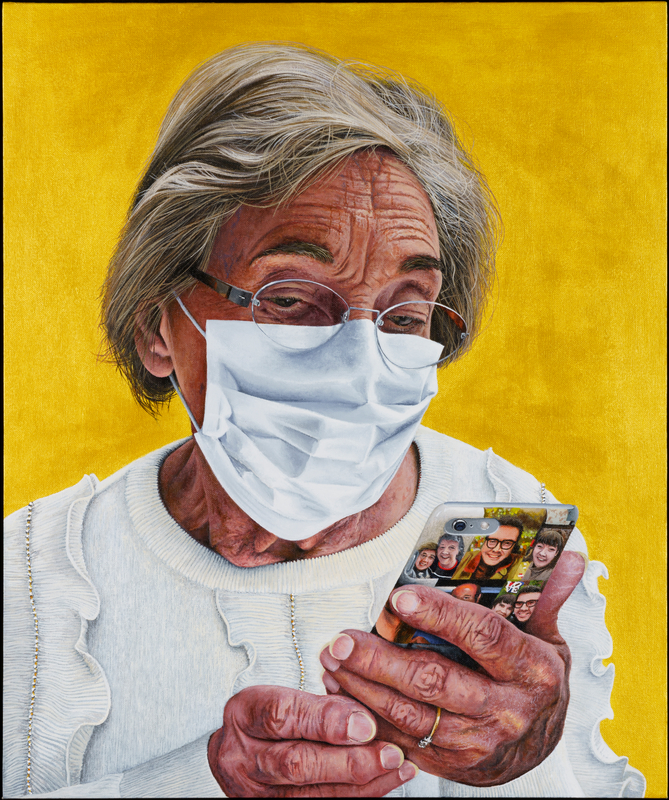

With the end of the great witch-hunts, and moving toward the Industrial Revolution, the popular imagination surrounding old women changed drastically – from the devious old hag to the helpless, silent matriarch. The growth of capitalism in an industrial and patriarchal society rendered elderly women useless for all intents and purposes. Often widowed, unable to work and too old to remarry, the old woman exists in a void: she is an eternal mother, silent, asexual, helpless.

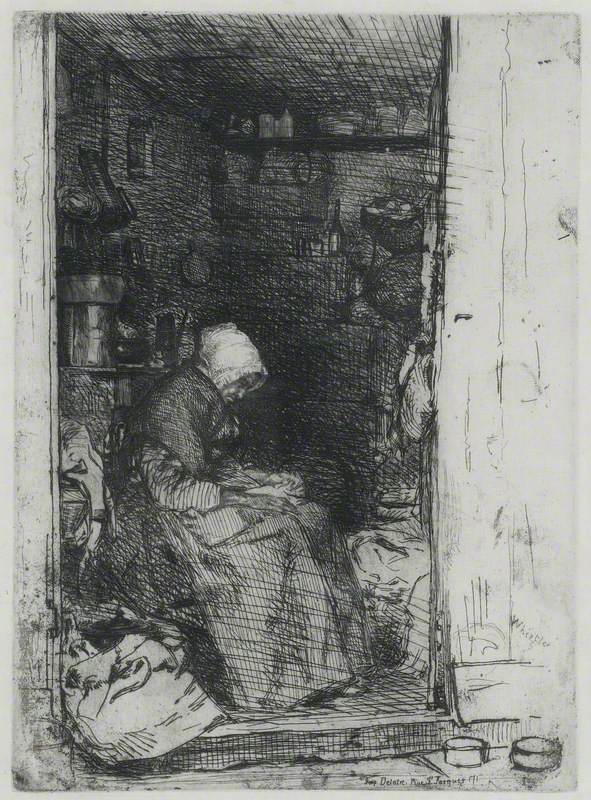

David Andre’s Old Woman shows a woman sitting on a chair, staring past the viewer. She is wearing a long black coat hiding the totality of her body, and her hair in a small lace hat. The flat grey tones of the painting serve to heighten the stillness and silence of the character, her slow drift away from life. Likewise, James Abbott McNeill Whistler painted several older women in similar postures, and using a comparable coding of his subject as silent, still and helpless. The most famous, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, shows the artist’s mother sat, dressed in black, and staring emptily in the distance. Other sketches and etchings carry out the same visual vocabulary, such as the small etching La Vieille aux

La vielle aux loques (Old Woman Sorting Rags)

1858

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

The subversion of this vision of the old woman as an irremediably vulnerable, weak, and placid figure was the prime motivation behind the making of American comedy Grace and Frankie. Created in 2015 by Marta Kauffman and Howard J. Morris, the series stars Jane Fonda and Lily Tomlin as septuagenarians whose husbands dump them after 40 years to marry each other. Naturally disheartened by the situation, the two women end up becoming unlikely roommates.

A significant plot point of the series begins in the end season two, when Grace strains her wrist due to acute arthritis, while masturbating with a vibrator, and the two decide to launch a sex toy brand for elderly women. When Grace announces her plan, her youngest daughter Mallorie asks: 'How do I explain to my children that their grandma is making sex toys for other grandmas?' Grace replies: '...we are making things for people like

Much of Grace and Frankie’s humour relies on their tribulations as older women, touching on many taboo subjects such as sexuality, medications and drug-use, and exploring, with nuance, more difficult topics such as memory loss, physical injury, and death. While the two friends sometimes fall victim to their old age, they resist their families' desire to see their vulnerability as a way to control and infantilise them, consistently asking their autonomy to be respected. This approach stands in opposition with both the stereotype of the 'hag' and the helpless, quiet, elderly women we have previously seen.

However, it is important to note that both Grace and Frankie in the storyline are extremely well off, therefore have the financial security to bounce back from the trauma of their divorce. What’s more, despite their age, both Grace and Frankie present as conventionally attractive, with the characters consciously styled to exist within western beauty standards: Lily Tomlin as Frankie is given a full wig of long grey hair, while Jane Fonda as Grace wears hair and eyelash extensions, and is always elegantly dressed with her make-up done. While this is explicitly addressed more than once in the series, it prompts the question of what kind of old women we are willing to see, and what kind of women we are willing to let grow old.

Although attitudes may have changed over hundreds of years, there is, perhaps, still a long way to go.

Mayanne Soret, Tabloid Art History