Queen Cleopatra VII is remembered as history's temptress, a queen adept in the art of seduction – the ultimate femme fatale. But her story isn't so simple. Cleopatra's destiny as the ruler of Egypt expected much of her, and she faithfully obliged.

Born in Alexandria, Egypt in 69 BC, Cleopatra hailed from the Greek-speaking Ptolemaic dynasty (named after Alexander the Great's general Ptolemy) which ruled Egypt for almost 300 years.

Just like any pharaoh of Egypt, her role demanded that she be a talented strategist and administrator. Not only that, history recalls that she was a polymath and academically accomplished, studying a plethora of subjects, including medicine.

Cleopatra testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners

1887, oil on canvas by Alexandre Cabanel (1823–1889)

Surviving evidence about the queen has been hotly debated throughout history, explaining in part why her image is so provocative. Her complex narrative was left in the hands of her conquerors – the Romans – so that over time her reputation as a diligent and cunning diplomat was replaced with simplified representations of her as a devious woman.

Mythologised in famous works of literature and art, popular depictions of Cleopatra have focused on satisfying our imaginations with outlandish tales which, although undeniably entertaining, are often retold with little proof that they actually happened.

First and foremost, Cleopatra's turbulent and violent relationship with her own family is often remembered. After the death of her father Ptolemy XII, Cleopatra and her co-ruler (and husband) – her younger brother, Ptolemy XIII – took control of the Egyptian kingdom.

In an attempt to depose his older sister, Ptolemy XIII allied himself with their half-sister Arsinoe IV, leading to a civil war known as the Siege of Alexandria. Ptolemy XIII reportedly drowned while trying to cross the Nile in 47 BC. Arsinoe was exiled and later murdered allegedly under the command of Cleopatra and her Roman allies.

In 46 BC, Cleopatra followed Julius Caesar to Rome, accompanied by her other younger brother (and co-ruler) Ptolemy XIV. Due to the fact that Egypt allowed polygamy, Cleopatra was married to both her brother (a customary practice during the Ptolemaic dynasty) and Caesar.

After Caesar's murder at the hands of Brutus and his political enemies in 44 BC on the Ides of March, Ptolemy XIV also died. According to historians, this was at the command of his sister in an attempt to consolidate her absolute power. His death allowed Caesarion – the son of Caesar and Cleopatra – to take the Egyptian throne alongside his mother.

Now a widow and at the epicentre of Roman affairs, Cleopatra began another romantic alliance with the Roman general Mark Antony, who had been a close supporter of Caesar.

Cleopatra's infamous romances were political strategies rather than blind passion. Egypt was highly reliant upon the favour of the Romans, as the dynasty was financially strained.

However, her relationship with Mark Antony was immortalised as 'blind passion' in William Shakespeare's tragedy Antony and Cleopatra, first performed in around 1606 to Jacobean audiences. The end of the play famously dramatised the suicide of Cleopatra when she is bitten by an asp (Egyptian cobra), a moment that would be retold for centuries to come.

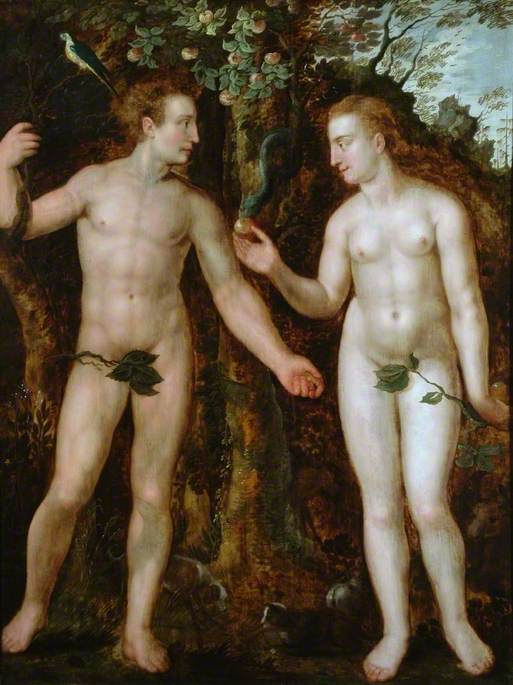

For many centuries, European painters have been drawn to the narratives of Cleopatra and her two Roman lovers.

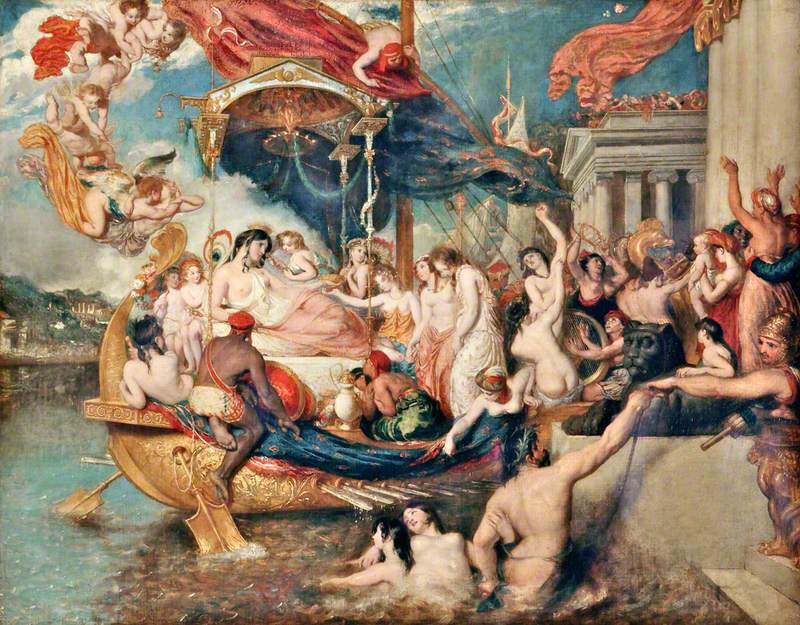

Artistic renderings of Cleopatra mirror what would have been desirable for women in different eras of history. No longer bearing darker features, Cleopatra is often recreated as a dainty, remarkably pale-skinned and, at times, even blonde-haired lady.

In this depiction by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, she is presented in western dress, elegantly hopping out of a boat, with an entourage of jesters and servants, flaunting wealth and majesty, and beguiling Mark Antony who succumbs to her charms.

The Meeting of Anthony and Cleopatra

c.1747

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

Cleopatra's racial ambiguity being overlooked by European painters is reminiscent of paintings of the Queen of Sheba who, in comparison to Cleopatra, is all the more enigmatic. Sheba's life is so undocumented, that her presence has become myth.

Both of these legendary historical women were reinvented by painters to conform to European beauty standards.

European painters told the story audiences wanted to see: the beauty, the drama, the smoke and mirrors.

Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra cemented the queen's influence in western literature and culture, making it a common trend for notable aristocratic women to have their self-portrait captured, posing as the queen, as seen in this portrait of Kitty Fisher by Joshua Reynolds.

Kitty Fisher (1741–1767) as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl

1759

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

The painting refers to one whimsical account, in which Cleopatra bets Mark Antony that she can host the most expensive banquet in history.

According to legend, Cleopatra gulps wine and vinegar from a cup, but not before dropping a rare, gigantic pearl earring into the concoction. As it dissolves, she wins the bet. The Italian painter Benedetto Gennari had also contributed towards this popular tradition.

Lady Elizabeth Howard (1656–1681), Lady Felton, as Cleopatra

1678–1689

Benedetto Gennari the younger (1633–1715)

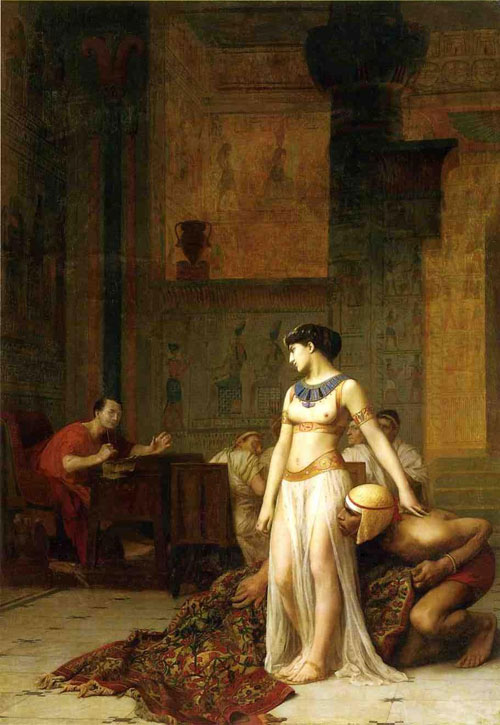

In another colourful tale, Cleopatra – a charismatic, bejewelled young woman, irresistible with her wit and charm – smuggles her way into Caesar's chambers, by tumbling out of an embroidered carpet.

Cleopatra and Caesar

1866, oil on canvas by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904)

The nineteenth-century artist Jean-Léon Gérome reimagined this scene by depicting a bare-breasted Cleopatra emerging from the carpet, distracting Caesar away from his day's work.

Most of these fanciful anecdotes can be traced back to the writings of the Greek essayist and biographer Plutarch, who was writing over 100 years after the death of Cleopatra. In his text Life of Antony, Plutarch describes Cleopatra as a leader of great intellect; her beauty is not distinct but her allure and charm have 'the greatest influence' on Antony.

Jumping forward, the most famous contemporary portrayal features Hollywood actress Elizabeth Taylor, who starred in the epic 1963 film Cleopatra.

This film ignited further popular reinterpretations of Cleopatra as a seductive siren, exuding unbridled erotic energy. She became known for her trademark 1960s makeup: thick, black kohl and vibrant, royal blue eyeshadow.

It is likely that the Egyptian queen really did wear blue eyeshadow, as ancient Egyptian documents suggest they believed the gods offered protection to those who wore makeup.

Hollywood's Cleopatra feeds our appetite for glamour and decadence, which is so blinding it eclipses the multiplicity of Cleopatra's persona it seeks to emphasise. The politics of the world's most powerful empires, led by a fearless empress, becomes something of a back story.

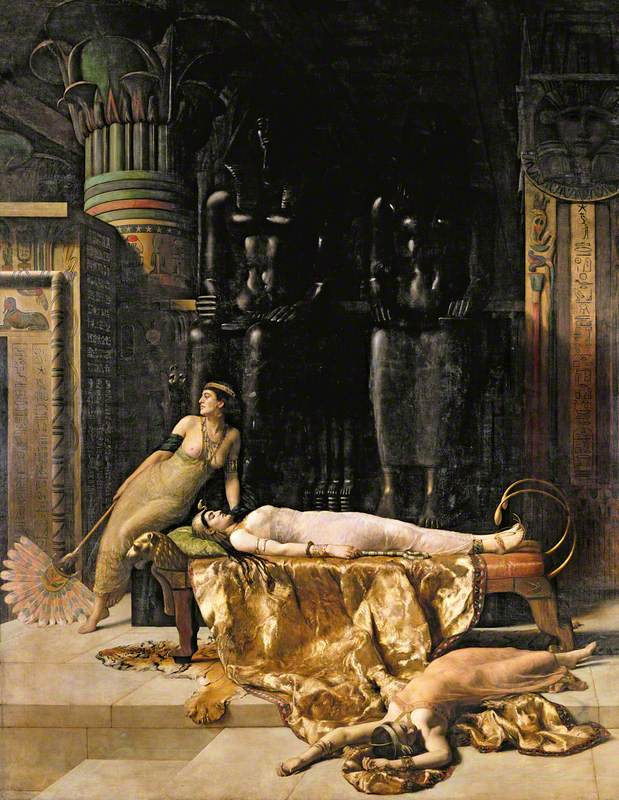

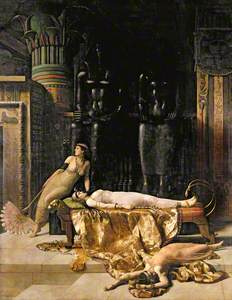

Art history, in particular, has focused on the fictionalised and tragic death of Cleopatra, rather than her abilities and contributions as a ruler.

Cleopatra assisted Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium during Rome's civil war in 31 BC. Eventually, they were defeated by Octavian – Caesar's chosen adopted son and heir – allowing him to take back rulership over Rome and its dominions.

The Flight of Antony and Cleopatra from the Battle of Actium

c.1897

Agnes Pringle (1853–1934)

In the aftermath of battle, Mark Antony and Cleopatra fled to Egypt. However, in his attempt for absolute power, Octavian invaded Egypt and eventually became the first Roman emperor, adopting the name Augustus.

With no future of political control and mistakenly believing that Cleopatra had already died, Antony died by suicide (by stabbing himself). Cleopatra followed suit, dying in August 30 BC. Her death marked the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, and the kingdom was absorbed into the Roman Empire.

Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium

Johann Georg Platzer (1704–1761)

In successive generations, poets and artists tended to reproduce the negative images of Cleopatra disseminated by the Romans, often presenting her as an inebriated, promiscuous woman. Equally, depictions of Mark Antony were often feminised, as a way to denigrate his image.

Such stereotypical portrayals of Cleopatra were conflated with representations of her sensational suicide by an asp. In earlier depictions, she was often portrayed semi-nude, reclining on a bed – showing her sexual prowess and exotic charm even at the moment of her own death.

These representations of a stone-faced, indifferent, nonchalant queen arguably only served to reinforce her reputation as being heartless. In this voyeuristic portrayal by Benedetto Gennari the younger the snake is merely an accessory.

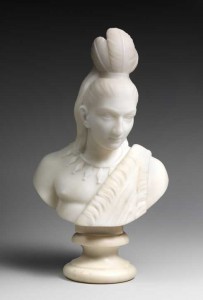

Over two centuries after Shakespeare's play, the African-American sculptor Edmonia Lewis unveiled a sobering portrayal of the death of Cleopatra in 1876.

A realistic confrontation, Lewis offered an empathetic approach to the suffering queen. The artist omitted the asp. Instead, at either side of the throne, identical sphinx heads represent the twin children she bore with Mark Antony. By changing the traditional narrative, the artist weaves in the sentimental nature of motherhood – something her male counterparts ignore in their portrayals.

The Death of Cleopatra

1876, marble sculpture by Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907). Gift of the Historical Society of Forest Park, Illinois

Cleopatra sculpted as a pharaoh on a high throne emphasises her autonomy even in death – the defiance to die at the hands of her victors marks her determination to write history.

Lewis was both criticised and praised for her poignant interpretation of Cleopatra's death, with several onlookers describing it as 'absolutely repellent', but it also gave her some notoriety – the sculpture became widely respected as one of the best of its time.

Her work offers a refreshing interpretation of an age-long tale. She reimagines Cleopatra with integrity and dignity.

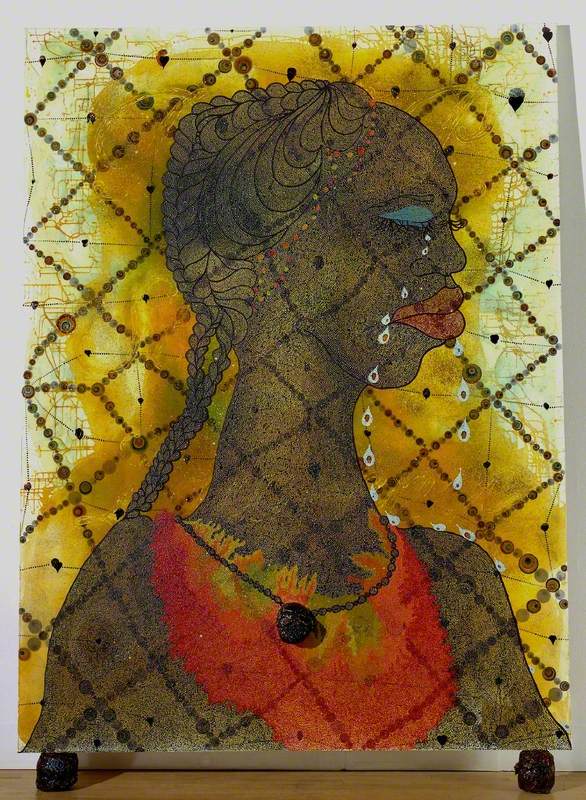

One of the most contemporary portrayals we have is this painting by Chris Ofili, who serves an unapologetic remodelling of a black Cleopatra.

Deliberately, Ofili references a long-standing tradition of European artists who have presented Cleopatra conforming to white beauty standards.

Ofili invites viewers to reinterpret the story and symbol of Cleopatra, prompting us to reimagine her in the context of contemporary culture.

Today Cleopatra's story is still remembered as myth. Undeniably, her story has fallen into the misogynistic trap of the nasty woman – the femme fatale trope. But that's not to say Cleopatra's reign wasn't bloody...

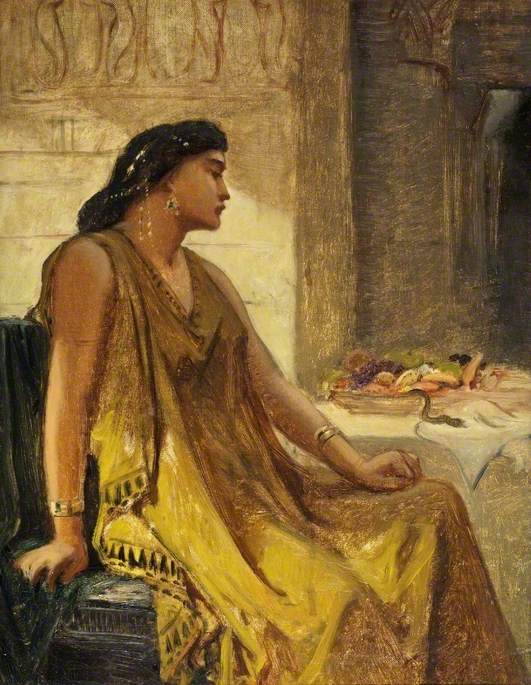

Cleopatra

1888, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

To secure her throne, Cleopatra most likely did have two of her siblings killed – a ruthless strategy that wasn't uncommon among power-hungry rulers of the ancient world. As a female leader, her position was even more fragile and at stake than her male contemporaries.

Cleopatra remains an enigma. However, we do know that Egypt flourished for a fleeting period of history under her reign. The lasting irony is that she is credited for profoundly influencing the Roman Empire, though they would spin their own version of the last non-Roman ruler of Egypt after her death.

Hermenia Powers, Digital Content Trainee at Art UK

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.