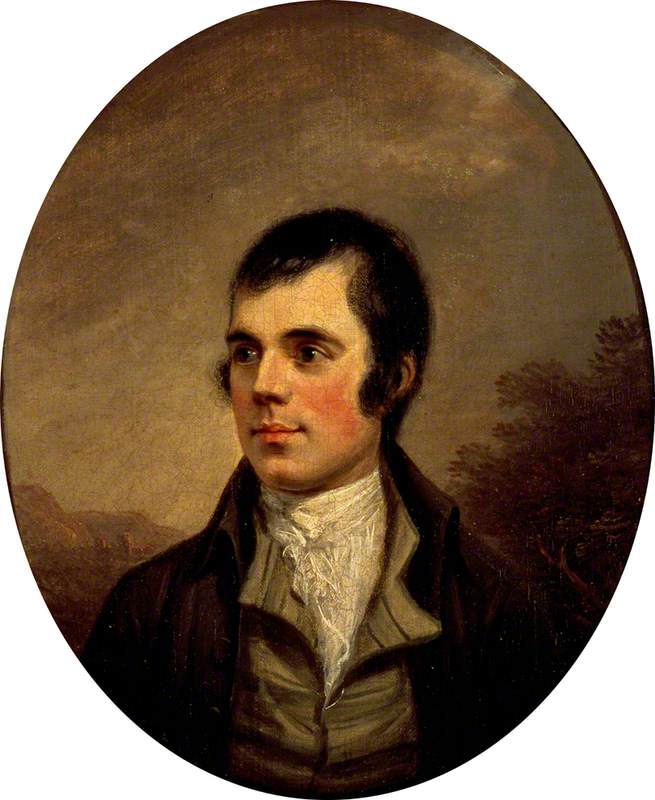

A proper Burns Supper is a real pleasure. The evening is full of good company and Scottish music, and it wouldn’t be complete withoot haggis, neeps ‘n’ tatties and a heartfelt reading of Address to a Haggis. As celebrations of the life and poems of Robert Burns approach, it’s a wonderful time to enjoy other art and artists from Scotland, too. Among visual artists from Scotland, I find the Scottish Colourists especially captivating.

The phrase 'Scottish Colourists' refers to four Scottish painters active roughly from the late nineteenth century to mid-twentieth century: Francis Cadell, Samuel Peploe, John Fergusson, and Leslie Hunter. They were acquaintances, and some of them close friends with one another. They shared many interests, chiefly an attraction to painting by the Impressionists and other avant-gardes in Paris who fall under the the umbrella of Post-Impressionism. Developments in chemistry and manufacturing also meant that new art materials were available to explore, including previously unavailable pigments. Within this innovative ferment, Cadell, Peploe, Fergusson, and Hunter began to make colour a principal character in their work. They gave colour a bold voice, one of many significant departures from traditional, academic painting techniques.

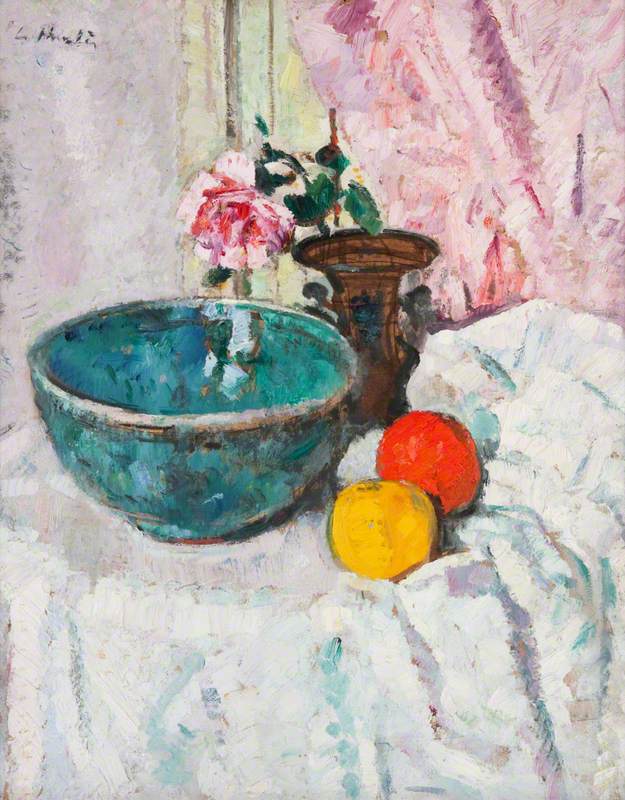

Still Life and Rosechatel

1924

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

I will always remember my first encounter with Still Life and Rosechatel by Francis Cadell. Even through my peripheral vision, the glowing palette of Cadell’s painting caught my eye. Upon closer inspection the colours seemed impossibly vibrant, like a firework that can still be seen in daylight. For as vivid and loud as the colours appear, the painting is also quiet. The brushwork is calm and deliberate, matching the mood of the carefully staged scene. The eye-catching palette invites your attention, but the diversity of brushmarks and subtle modulations of colour invite you to soak the painting in slowly.

It is clear why a work like Still Life and Rosechatel is categorised as 'Colourist' in style, though many works by the other Colourists, and even many other works by Cadell, are less overtly interested in saturated primary and secondary colours. Although they are less bold, the works are equally appealing and innovative, in part because the Scottish Colourists were attracted to progressive painters in Paris and London, drawing inspiration from Manet, Cézanne, Matisse, and many others.

What I find so interesting about paintings by Cadell, Peploe, Fergusson, and Hunter is how they employed these new ideas about art while drawing inspiration from their lives in and outside of Scotland. It’s clear that the Scottish Colourists were paying close attention to the world around them. Sometimes this is evident in skilfully painted portraits or carefully replicated optical effects like reflections and shadows. Other times themes are pulled from local predecessors and older European painting traditions, like the Glasgow School and Dutch flower painting respectively.

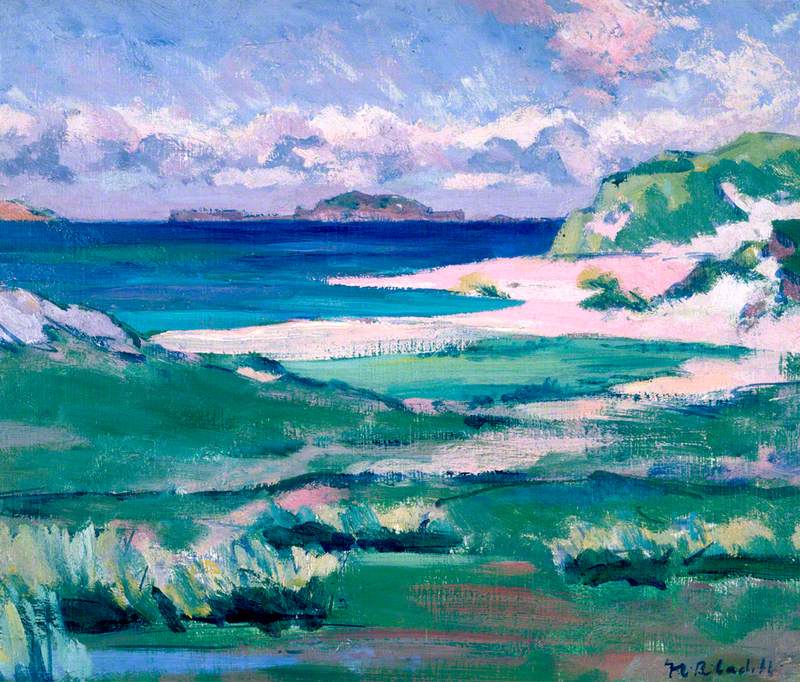

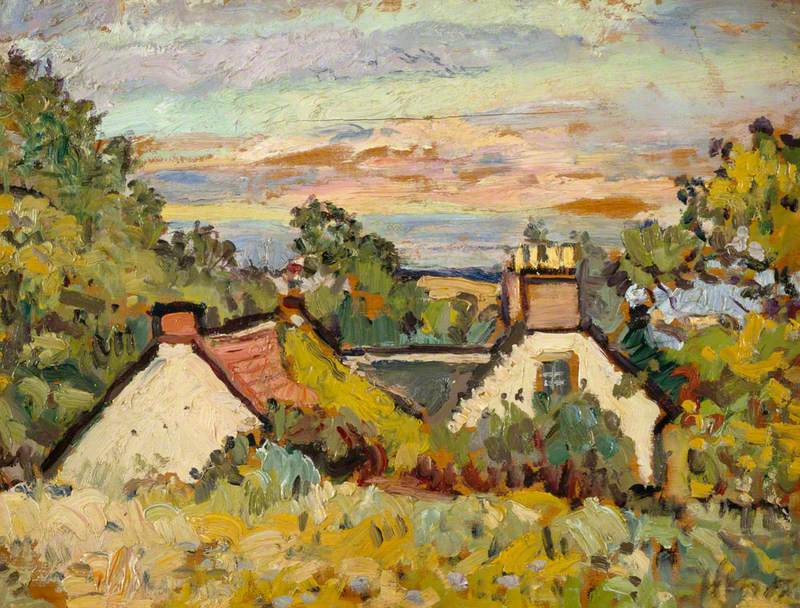

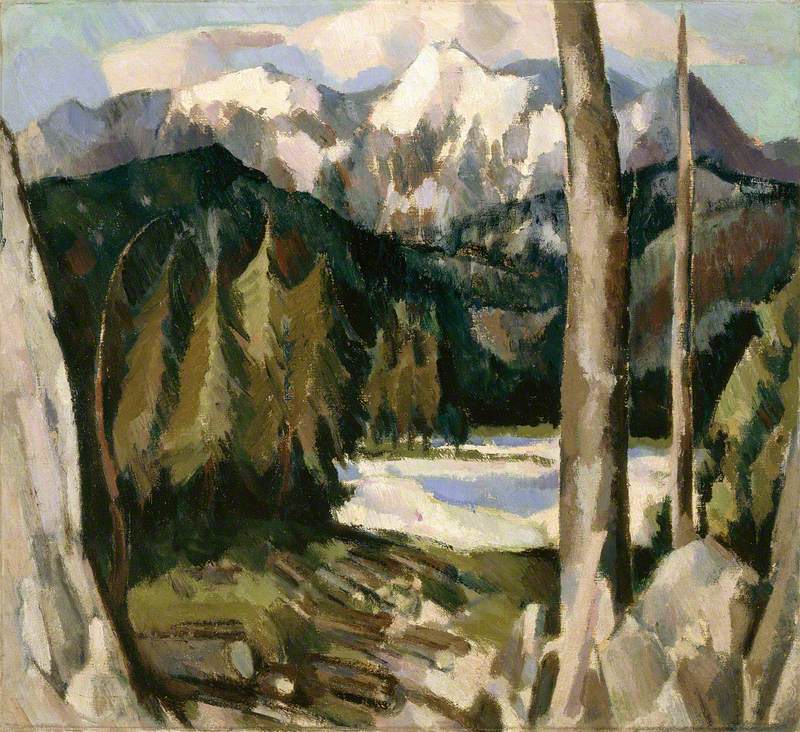

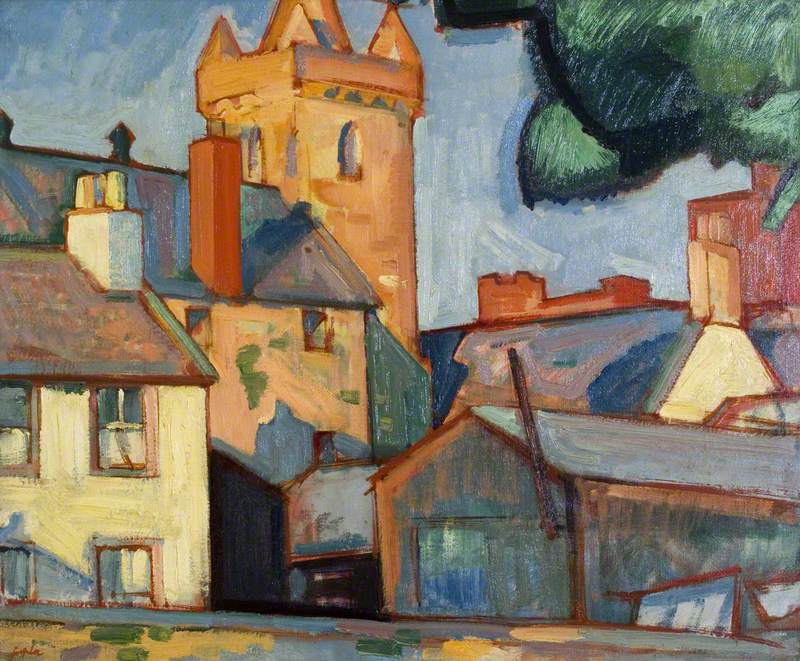

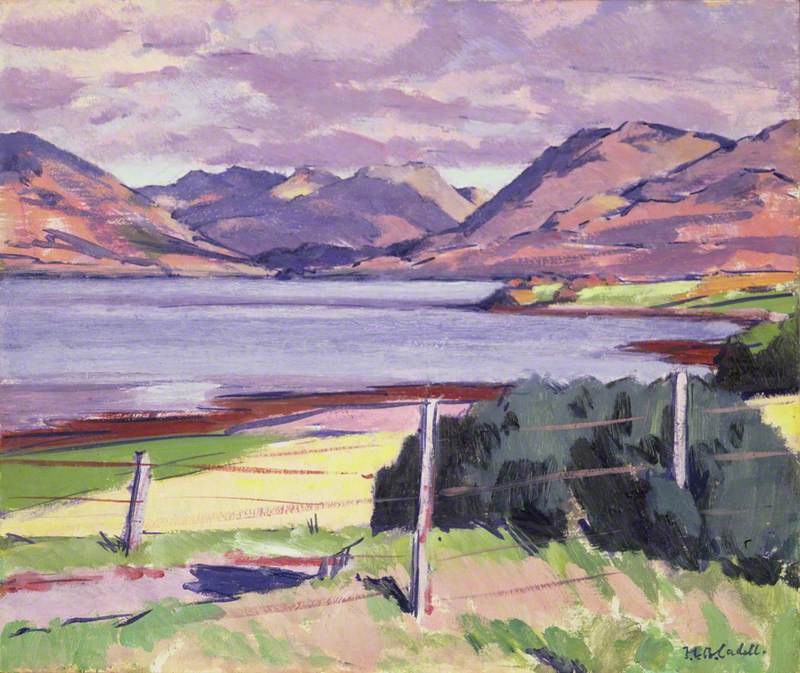

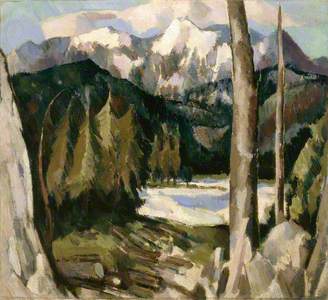

This heightened sense of awareness and interest in their surroundings is perhaps most acute in the landscapes of the Scottish Colourists. They captured the hues, textures, and terrain of Scotland, striking a dynamic balance between faithfully representing Scottish landscapes and sincerely exploring their new mode of painting.

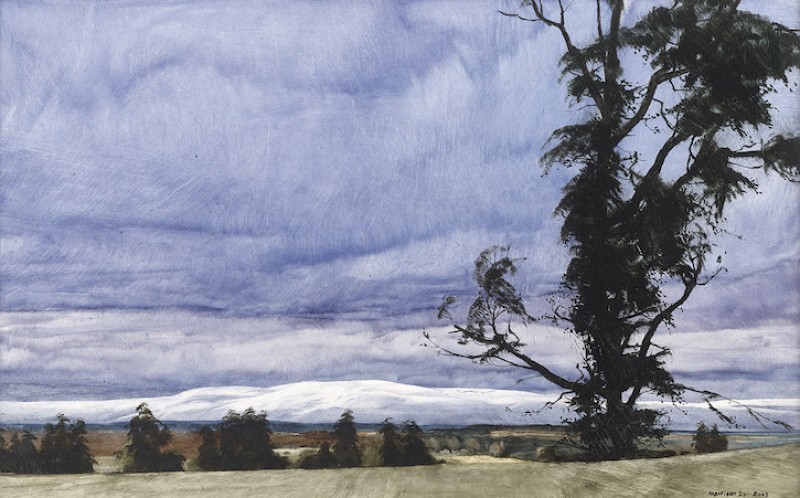

Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937)

Ben More from Iona is a fantastic example of such a landscape painting. Cadell painted many similar scenes, each reproducing various atmospheric effects and views of the mountain peak. His series of watery landscapes from Iona is reminiscent of Monet’s investigations of light falling on the Rouen Cathedral. Painting in Iona roughly two decades after Monet painted his Rouen series, Cadell’s paintings are less scientific yet, in some ways, more specific. I can imagine the light Monet painted falling on buildings in other places around the world. Cadell’s paintings are different. The rugged topography emerging from jewel-toned water, the colours and shifting light and atmosphere belong only to the west coast of Scotland.

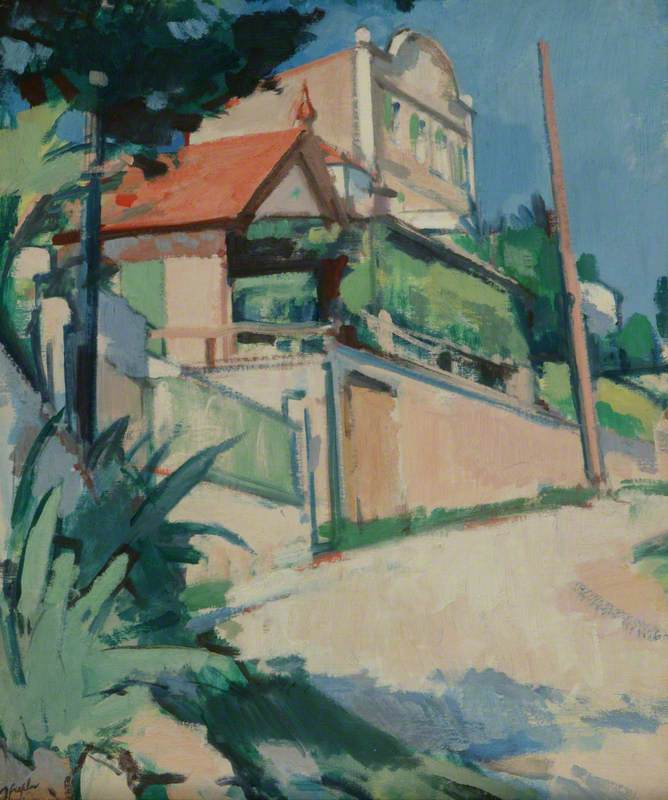

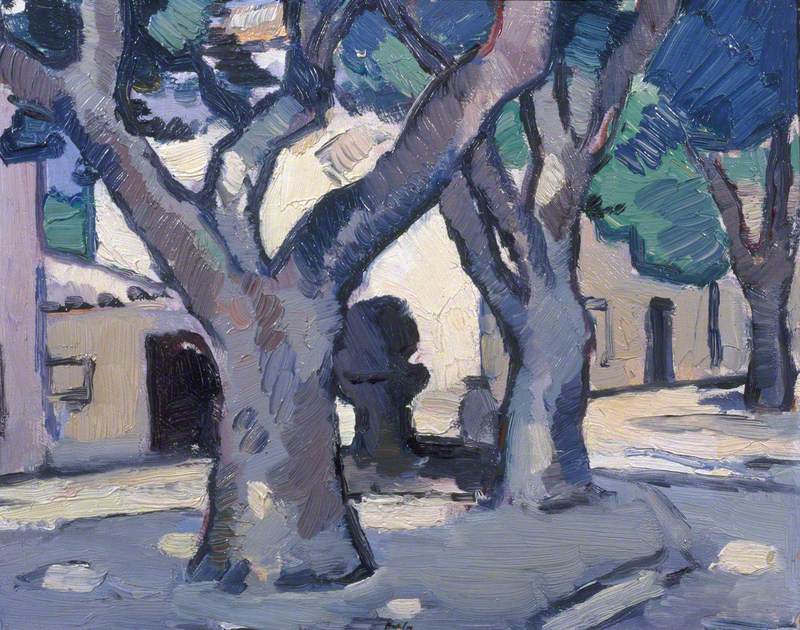

Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935)

The Scottish Colourists also took inspiration from landscapes outside of Scotland. The Aloe Tree demonstrates Peploe’s interest in the Mediterannean and displays a palette that he made use of in many works. The lush greens and greyish lilac hues that dominate the picture almost seem plucked from Scottish heaths and grasslands. But the scene is also distinctly not Scottish. The sun-basked architecture and the spikey aloe plants in the foreground indicate a warmer climate. The dusty looking road seems parched and arid. The character of the setting is cemented through details like the skillfully constructed slope of the hill and the tilting timber pole that seems to have shifted over time.

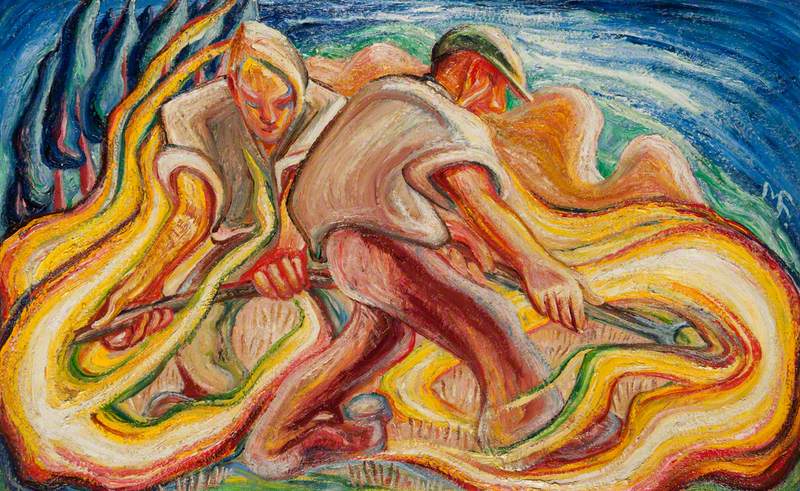

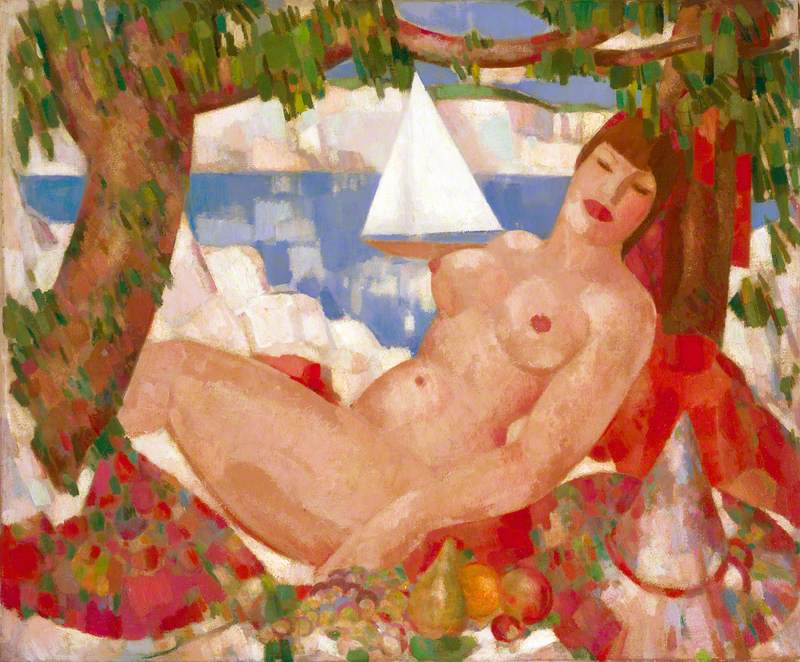

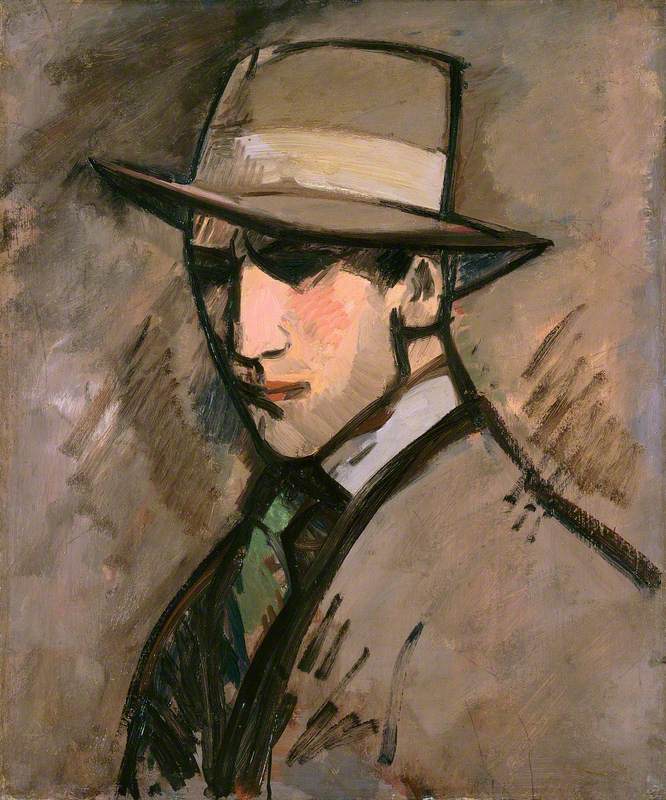

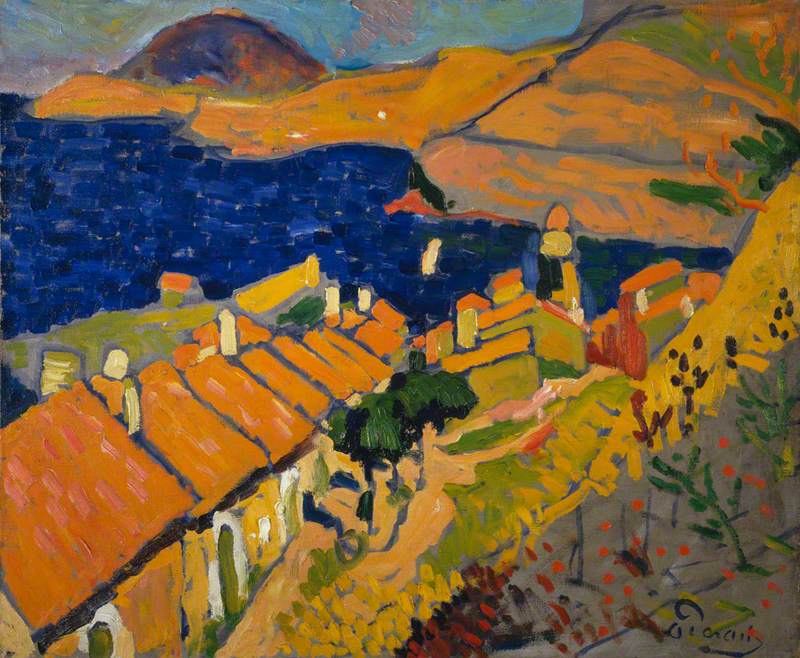

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

Apart from landscapes, the Scottish Colourists painted exciting portraits, compositions inspired by Cubism, and memorable still lifes. Among the group of artists, Fergusson was the most interested in portraiture. Born in 1874 and painting until his death in 1961, he witnessed both World Wars and his art constantly changed alongside the world around him. I am particularly fond of his pre-First World War portraits: there is a youthfulness about them and they’re painted in a crisp, direct manner.

In The Red Shawl Fergusson uses his new Post-Impressionist language to paint a portrait of a compelling and fashionable woman. Her expression is calm and commanding, even as paint marks whirl around her and commingle into a buzzing floral pattern. She is comfortable in this confidence, a fact reinforced by her striking red shawl. Although the sitter’s face and torso are painted in a smooth and clear style, the bottom half of the painting begins to dissolve into muddy, sumptuous brush work. For me, this transition is the most dazzling at the end of the woman’s shawl: the red fringe hovers between dangling textile threads and blobs of dripping paint.

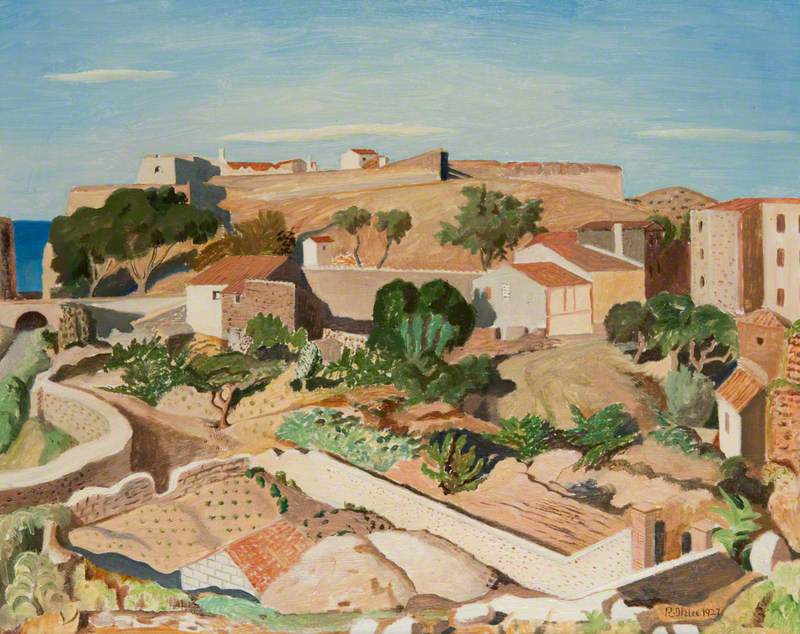

George Leslie Hunter (1879–1931)

The image of flowers and fruit arranged on a table is one that Leslie Hunter painted numerous times. Specifically this table, with a cropped view of a door or panelled wall partially draped with colourful fabric. The Scottish Colourists were interested in patterned fabrics and textiles imported from Asia, though in Hunter’s Tulips the fabric’s pattern dissolves into a network of short, thick brushstrokes. In fact the entire image is painted in an unapologetic, chunky style that I find incredibly exciting. Hunter plops punchy splashes of colour across the canvas, but the balance of dark and bright colours paired with a chorus of nuanced pastel whites resist any air of brashness.

In a different series of work, Hunter used a softened iteration of his thick, bold style in compositions inspired by Dutch paintings from the seventeenth and eighteenth century. The backgrounds become dark and the colours less vivid, but equally compelling. Although the Dutch inspired works are less bright, they are nonetheless more luminous, more interested with the dramatic cascade of light across objects. Roses in a White and Blue Vase seems to glow. Light penetrates the warm-coloured wood and catches in semi-transparent flower petals which beam against rich shadows.

The shift in style in Hunter’s still lifes is one of many that can be tracked throughout the works of the Scottish Colourists. The four artists witnessed tremendous changes in art and in the world during their lifetimes, and each artist reflected on these changes in highly individual progressions throughout their creative careers. Their life stories and paintings continue to engage me, in part because of their interests in the dynamic evolution of art and society in early twentieth-century Europe. I think their geographic location ideally situated them to have exposure to goings on in France while having the freedom to explore painting in exciting, novel ways. The four artists were among the first in Britain to recognise the importance of the Post-Impressionists. This foresight and their commitment to redefine painting – often from easels planted in Scottish soil – draw my attention time and again. And when you’re inspired to visit the bonnie land of Robert Burns but unable to make the journey, a landscape by one of the Scottish Colourists is the next best thing.

Riley Cruttenden, Fulbright Recipient, University of Glasgow, MLitt Candidate in Technical Art History