Grandeur, safety, a sense of elegance and calm. Across the country, we file past eighteenth-century portraiture collections and bask in the alien glory of their appearance. Huge elaborate clothing, big hair, stark painted faces, bewigged and bejewelled ghosts stare impassively back at us from their aesthetic pinnacle.

The great ladies of the Georgian era revelled in visual extremis, and we, in turn, are used to their presence in galleries. Not the oldest work in collections, nor part of the tidal wave of Victorian art to come, they are nonetheless a touchstone in many galleries.

Let's shrug off the safety of these works though and see them in a starker light. These women are caught in a moment of self-destruction – styling and cosmetics are literally killing them.

Big hair hides a variety of secrets. Syphilis, for example, in advanced stages causes hair loss and open sores. Fashion developed to hide this with big backcombed styles, hairpieces and later powder to thicken the illusion.

Lice were unavoidable and common, so much so that ladies' lice combs developed into elongated forks that could be used to itch the scalp without dislodging the style. When an expensive hairstyle was set, washing became unthinkable, your hair was an investment. Weeks, perhaps months, could pass without washing your scalp, hot heads covered in products and pig fat to hold it in place must have been unbearable.

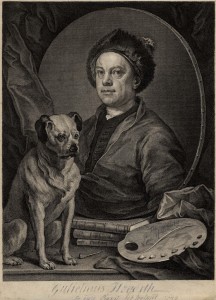

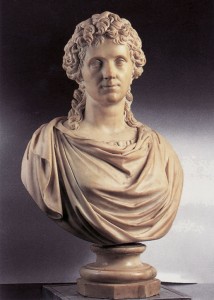

Anne Luttrell (1743–1808), Duchess of Cumberland

c.1773

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Consider this when looking at this portrait of Anne Luttrell (1743–1808), Duchess of Cumberland, by Thomas Gainsborough. Elegance erodes into empathy and discomfort as we look at her huge hairstyle... Are you scratching your own head yet?

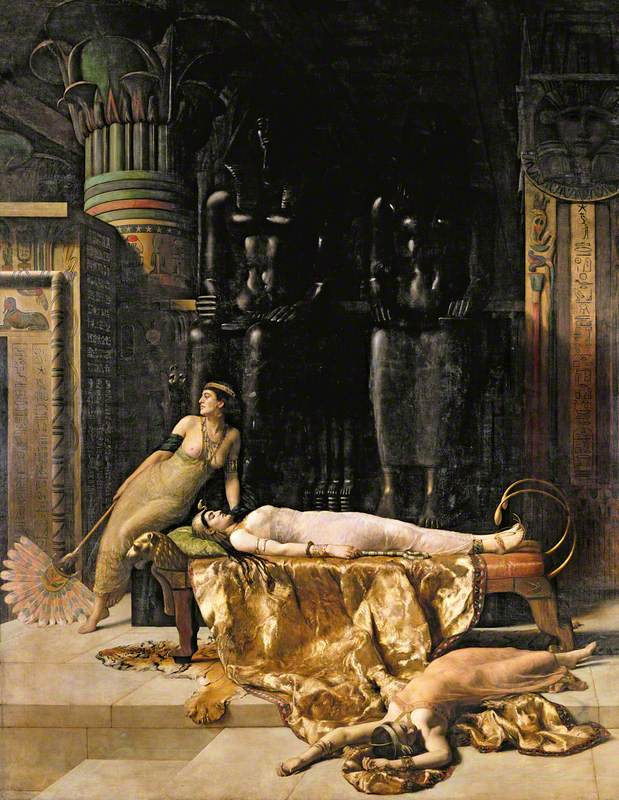

Cosmetics were far more deadly. Let's start with the whimsy – fake eyebrows could be fashioned from the skins of mice. An oddity for today and revolting to some but not harmful. Face paint, however, was lead-based, sometimes mixed with manure for traction or vinegar to thin out the consistency.

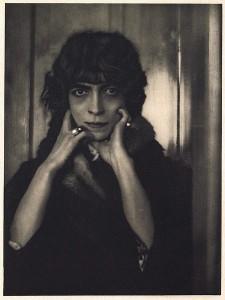

As we stare into the face of the beautiful Mrs Siddons (in a painting after Thomas Gainsborough), a chilling realisation seeps into us as viewers... She's got poison on her face.

A poised, human intelligence registers, dramatically set with large hair and achingly sophisticated contemporary fashion. A face covered in lead, which routinely and over long periods of time poisoned her contemporaries with horrifying results. Symptoms of lead poisoning include abdominal pain, aggressive behaviour, constipation, sleep problems, headaches, irritability, loss of appetite, loss of teeth, fatigue and high blood pressure. Apply this to her beautiful portrait and our view shifts dramatically – and possibly fatally.

Beauty becomes a grotesque visage of pain. A pain we, as art viewers, are desensitised to by the elegant repetition of images we are used to in galleries. I considered this recently, standing in front of the beguiling beauty of Mrs Siddons by Thomas Gainsborough at The National Gallery.

Three-quarter length, she looks beyond us, seemingly confident in how she is viewed and objectified. The former actress, known for her tragic roles to contemporaries, is dazzlingly glamorous. Consider her symptoms and pathology breaks the spell abruptly though, and I found myself deeply uncomfortable in her elegant presence.

Sometimes the danger of cosmetics was vivid, as seen in the story of Maria Gunning (1733–1760), here pictured in a painting attributed to Allan Ramsay.

We see her as a prime beauty – youthful, rich and with flawless symmetry to her face. She is idealised as in bloom, echoing the rose in her hair. The image is wistful, filled with a dreamy lethargy – Georgian aesthetic perfection laid out like a road map for all to follow.

Maria Gunning was remembered by contemporaries and later generations as a cautionary tale on vanity. Her 'addiction' to cosmetics was noted, with one famous story recounting how her husband banned her from using cosmetics due to the effects on her health. Undaunted, she arrived at dinner in full face. This would have included rouge mixed with mercury, a face of lead paint dusted with flour for extra whiteness, and a teeth-cleaning solution made from sulphuric acid forming a bright yet deadly smile. Maria's husband, upon seeing this, famously used a handkerchief to wipe away her make-up publicly in an act of abuse and humiliation.

When she died at the age of just 27, it was widely assumed she had succumbed to her extensive use of make-up – although no evidence for this exists, the tale began to spread. 'Tragic' Maria died trying to meet contemporary beauty standards. Within a generation, this make-up style disappeared as naturalism became the vogue for the early nineteenth century.

Let's leave this grisly and uncomfortable cult of beauty by reflecting on Portrait of a Lady in the style of Joshua Reynolds at Glasgow Museums Resource Centre. She radiates energy, poise and life. I wonder beneath the fake hair, lead and mercury how she felt, though? Empathy comes as a gut punch for me now whenever I see works like this. How about you?

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator