Watercolour of two pots in the Museo Nacional in Lima, Peru, made by Adela Breton on her tour of South America in 1910 .jpg)

Brought up in Bath, Adela Breton (1849–1923) was an archaeological copyist, researcher and watercolourist. A lady of leisure and private means, she devoted her time to her interests in history and geology. She was an intrepid traveller and failed to conform to the stereotype of the Victorian spinster, journeying extensively in Mexico and other Central American countries, accompanied only by her Indian guide and companion, Pablo Solorio.

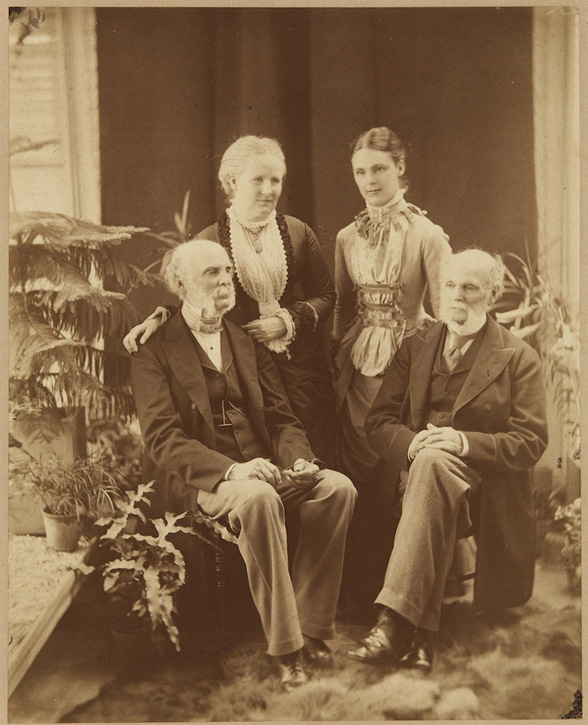

Family portrait: a young Adela Breton with her mother Elizabeth, father William and his twin brother

She spent much of her time in Mexico and worked there with archaeologists. As an artist, she painted for pleasure and also for work. To preserve them and make them accessible, she copied wall paintings in ancient Mexican temples, already damaged and rapidly disappearing during her lifetime.

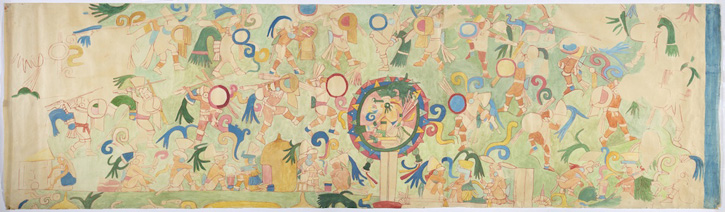

A section of Adela Breton's copy of the frieze on the Acancéh temple, showing gods and the glyph for water, with damaged areas left blank

Little known in her own country, in the Americas Breton is revered by scholars of Mesoamerican art and culture, especially for her watercolours and tracings of the frescos of the Upper Temple of Jaguars at Chichén Itzá in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula.

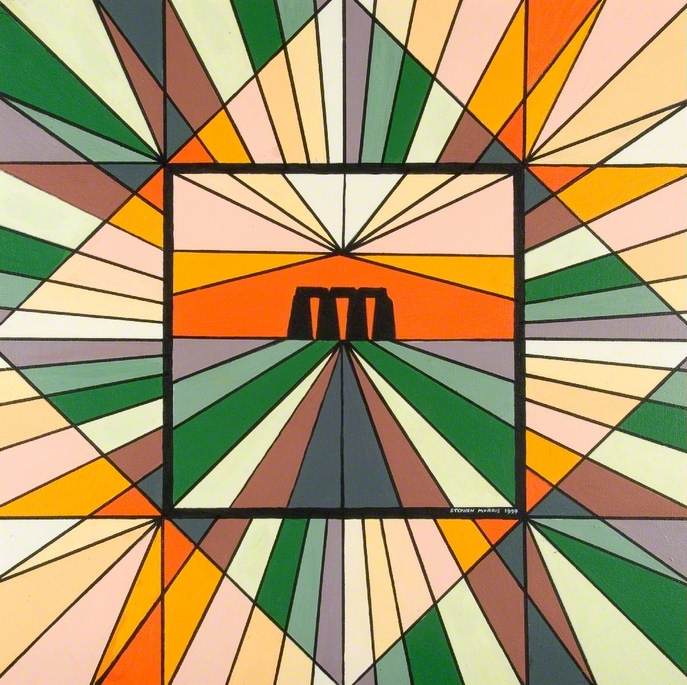

Copy of the lower part of the south west wall of the Upper Temple of the Jaguars, Chichén Itzá, Yucatan, showing victorious warriors around the captured Sun Disc; the damaged areas are left blank

The inner chamber was painted with battle scenes, although much was already lost by the time Breton began work in 1900. At various times over the next seven years, she traced the whole wall decoration, making the only full colour copy. By the time colour photography was available, most of the paint had gone: eroded by bat droppings, rain, sun and tourists. Breton’s copy is the only full record of the wall paintings as they existed in the 1900s.

From 1899 Breton loaned material to the newly established Bristol Art Gallery & Museum of Antiquities. In her letters, she urged the Director to establish it as a centre for Central American study in Britain and, in 1923, bequeathed her entire collection to the Museum. In 1946, after several years of cataloguing the collection in batches, the curator G. R. Stanton arranged a display of the larger tracings. After Stanton retired, little work was done on the Breton Collection until the 1960s when a new curator, recognising its importance, carried out further detailed cataloguing, leading to some of the paintings being published by Arthur Miller, Professor of Art History at the University of Maryland.

Watercolour by Adela Breton of the east façade of the ‘Nunnery’, with the ‘Church’ at Chichén Itzá, both buildings heavily decorated and with hook-nosed masks of the rain god Chac

In 1989, Bristol Museums mounted a major exhibition of Breton’s work, The Art of Ruins: Adela Breton and the Temples of Mexico, followed by a national tour and, in 1993, a major exhibition at the Museo Nacional de Historia, Mexico City. Individual paintings have since been loaned for exhibitions in Germany and Mexico, and Mesoamerican scholars often request access to view the works.

A petroglyph carved on a rock near Tula in Hidalgo state, showing the god Centeocihuatl, the god of maize

In the 90 years since Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives acquired the collection limited conservation has taken place due to lack of funds. In 2001, a conservation survey highlighted that inadequate storage of such fragile works was restricting wider access, due to the high risk of damage through unrolling and re-rolling.

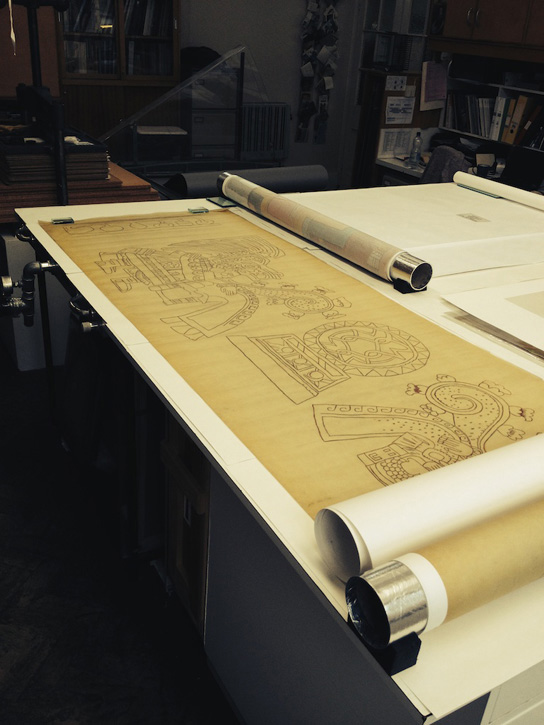

Today, advances in conservation, storage and digitisation techniques present an opportunity to preserve the works in perpetuity, allowing scholars greater access and to increase knowledge and understanding of archaeological methods employed in the early twentieth century. Over a period of about 36 months, thanks to a grant from the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives are undertaking conservation, photography, digitisation, and promotion of, as well as research into, about 500 items from the Breton Collection. Conservation and improved storage of the large tracings has allowed proper photography of these internationally important artworks.

Art UK Digitisation Services has been working with Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives on the project and has completed the first phase of photography, creating high-resolution images of over 150 very fragile tracings of the frescos at Chichén Itzá. Some are as large as 700mm wide and 3000mm long. The long tracings were photographed in sections and digitally stitched together to give a high-quality image of the whole. In the past, only transparencies of sections or poorly aligned overlaps were possible. The tracings were photographed using a flat-photo setup. To ensure safe handling, the project’s Paper Conservator, Pavlos Kapetanakis, was on hand during photography, and carefully unrolled the tracings onto white paper, using another tube to re-roll the photographed sections.

One of Adela Breton's works laid out during photography

Art UK Photographer Dan Brown reported that the ‘main challenges were the physical size of the objects, particularly the ones that were on long rolls of paper. Some images had to be created from as many as five separate photographs being stitched together. By digitising the collection, the digital copies of the objects can be studied in detail without requiring handling of the delicate originals, and they can also be made accessible online. Some of the larger full-scale copies that Adela Breton made were drawn on rolls of paper similar in size to wallpaper rolls, but on several rolls, each one recording the space above the other. For the first time, these can be combined digitally and seen as originally intended.’

Photographer Dan Brown with one of Adela Breton's works, one section of the copy of the frieze on the Acancéh temple, laid out in the conservation studio

Phase two saw the completion of the photography of over 300 watercolours on paper, over 80 printed photographs, two photograph albums and 13 sketch books.

‘It is a remarkable body of work from a woman who considered herself a semi-invalid and was ill with malaria and fever almost all the time she was in Mexico. Without Adela Breton’s copies, the wall paintings would today be known from a few fragmentary copies made in about 1900 and any photographs taken later, once the paintings had been further damaged and eroded. Very little now remains in situ.’ Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives is very grateful to the Esmée Fairburn Collections Fund which has allowed the Museum to carry out work that would not otherwise have been possible.

For more information on Art UK Digitisation Services, please contact Camilla Stewart (camilla.stewart@artuk.org).

Sue Giles, Senior Curator of World Cultures, and Valerie Harland, Head of Development, Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives