At the Collège de France in 1923, the students who gathered to listen to a speech by Jean Cocteau – artist, poet, and flamboyant staple of Parisian bohemia – were in for a surprise. 'I invented the disappearance of the skyscraper and the reappearance of the rose', he proudly announced. He had, apparently, initiated a great change in art. No longer would it concern itself with the chaos of modernity, but would return to its former quest for beauty.

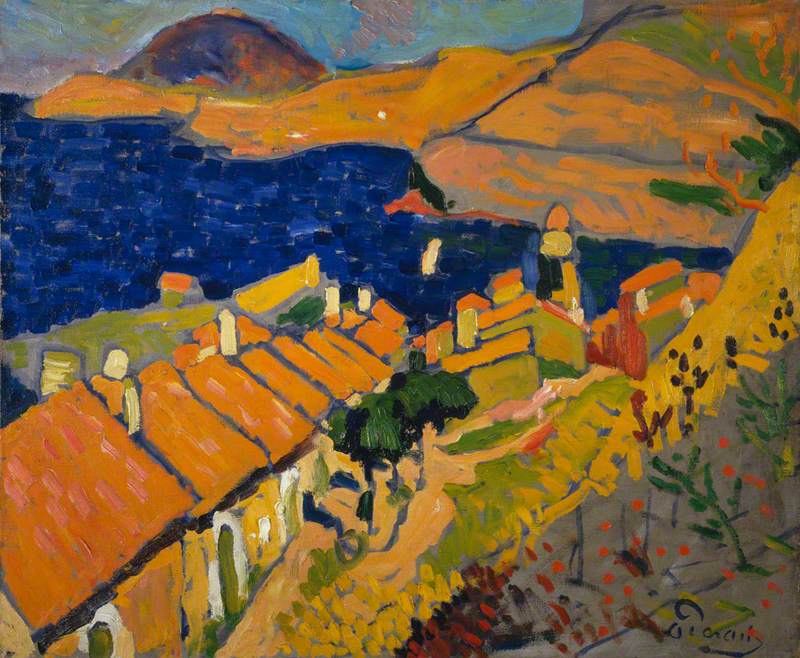

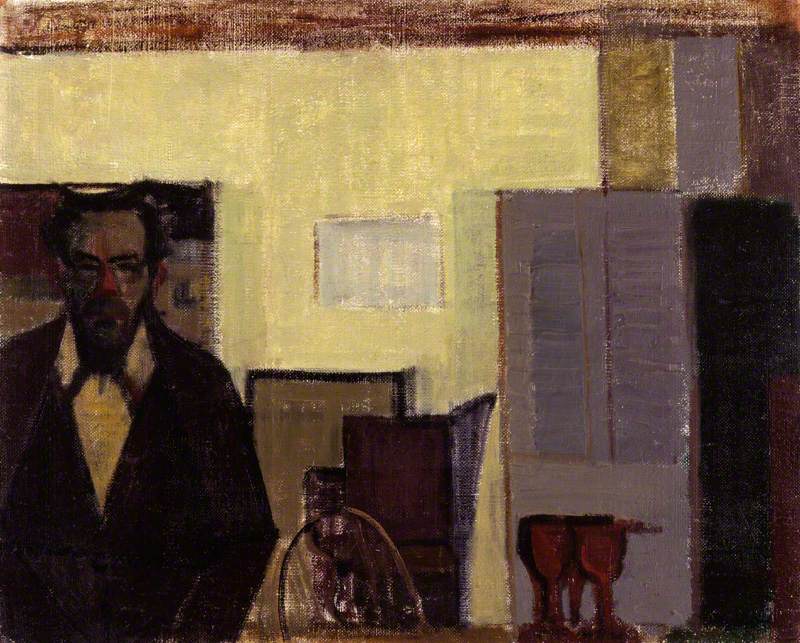

A relatively minor artist, Cocteau had, of course, not invented anything. But there certainly was change in the air. In Paris, Picasso was abandoning the chaos of Cubism, Matisse the frenzy of Fauvism; in Berlin, Otto Dix rejected his roots in Expressionism; in Milan, the key exponents of Futurism had turned their backs on the machines they once worshipped. The ringleaders of modernism in Europe's cultural centres were distancing themselves from the noise, fragmentation, and avant-gardism that had made them famous in favour of the stability and simplicity of a new classicism.

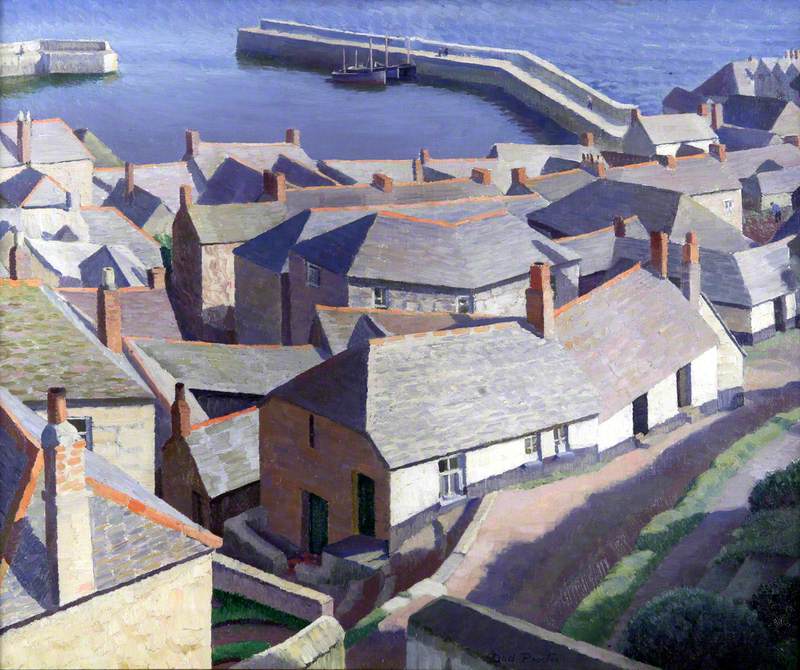

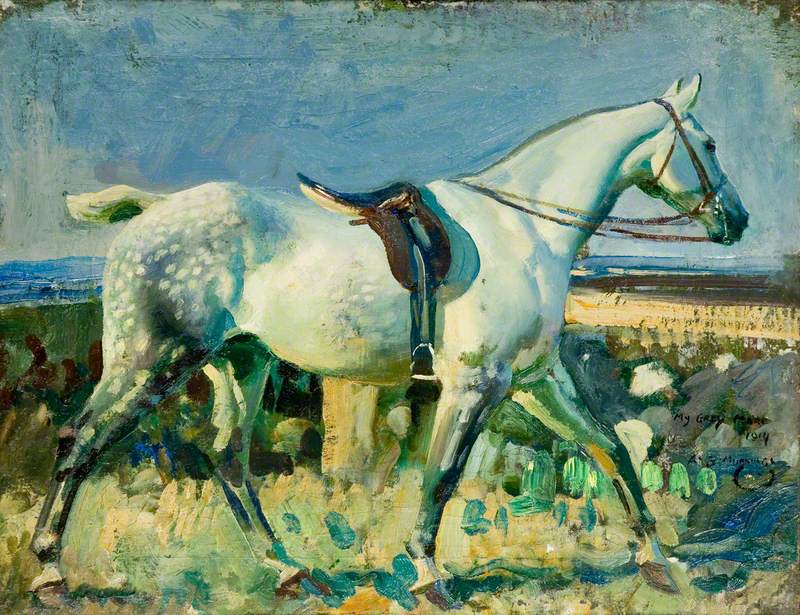

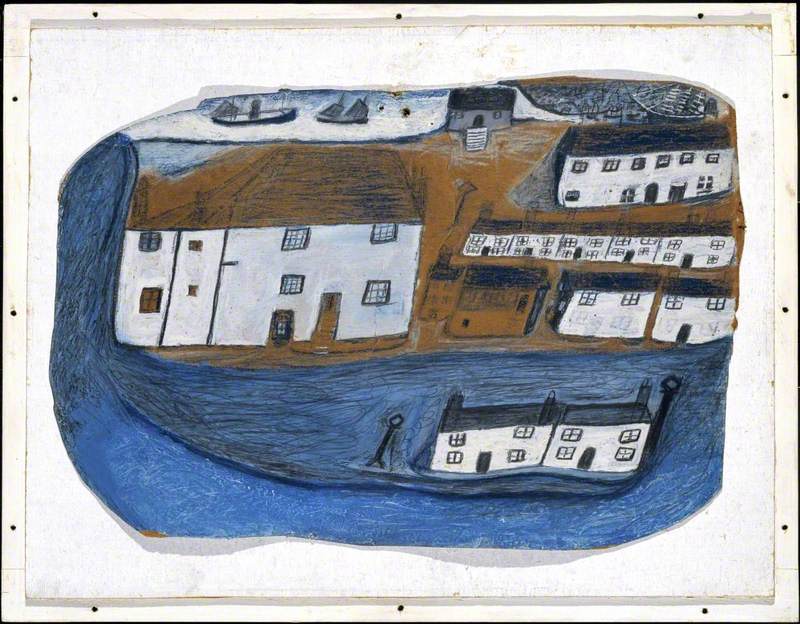

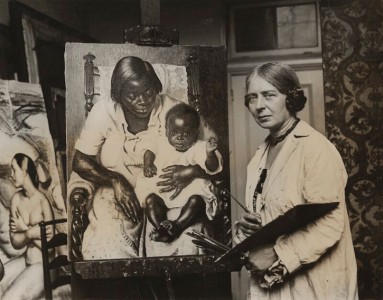

If this news reached Newlyn, Cornwall, the circle of painters gathered there may well have wondered what all the fuss was about. For them, fidelity to nature, a good eye for design, and a restrained, precise attitude to their subject matter were simply the hallmarks of a job well done. Their gently bohemian lifestyle and equally reserved manner of painting is perhaps best summarised by the 1926 painting Early Morning, Newlyn by the artist Dod Procter, soon to become the town's most celebrated resident.

Seen from a high vantage point, a jumble of rooftops and chimneys echo each other's lines and soft greys, umbers, and creams before giving way to the sea, a flat stretch of placid blue. A few early risers draw the eye – a diminutive workman sweeps the streets, and three figures wander along the pier. Despite its small-town subject, there's nothing outmoded about Procter's style – her mastery of tonal and formal harmonies bring a flavour of post-impressionist Paul Cezanne and Cubist progenitor Georges Braque's southern France to Cornwall.

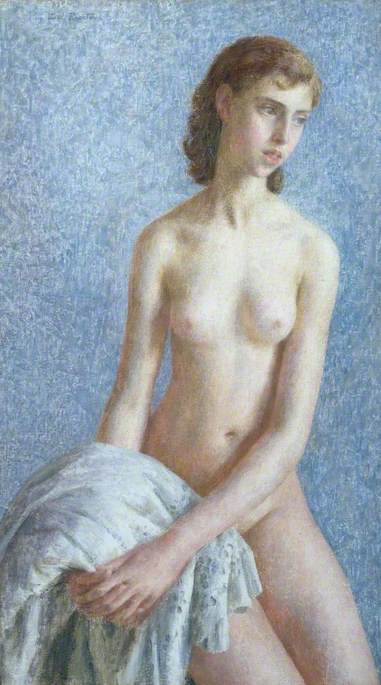

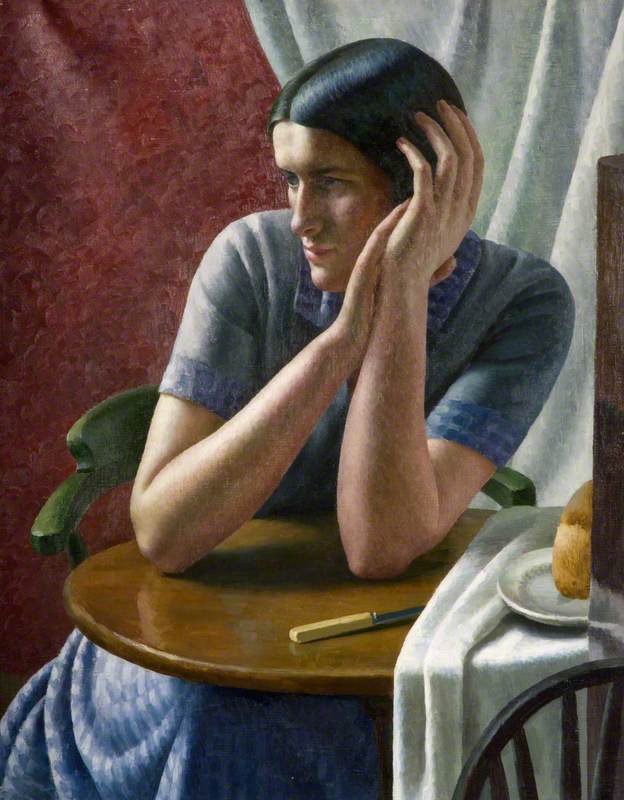

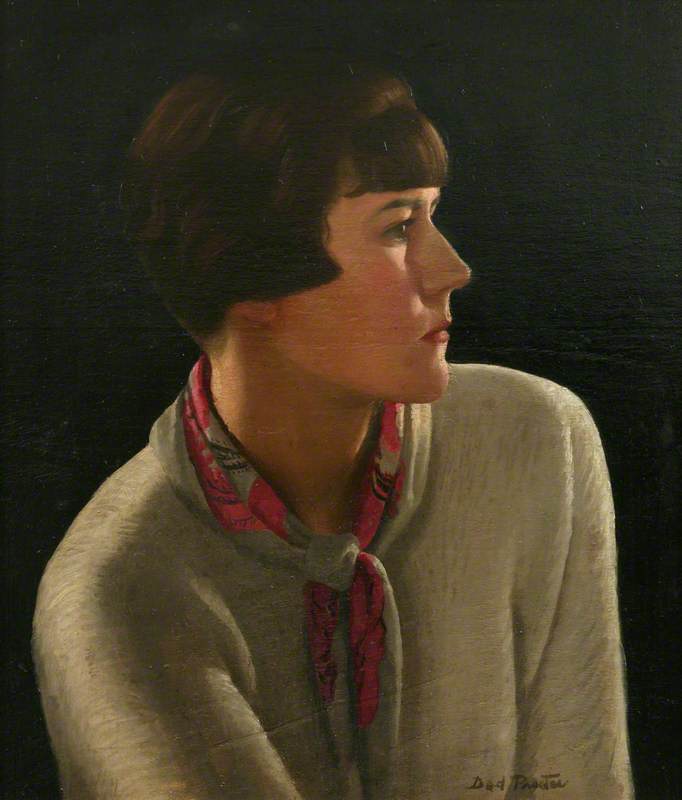

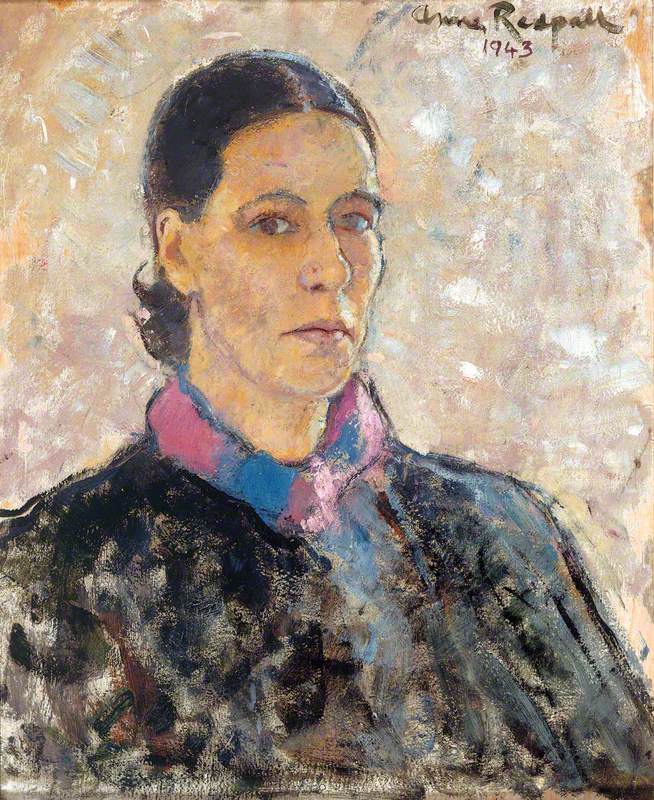

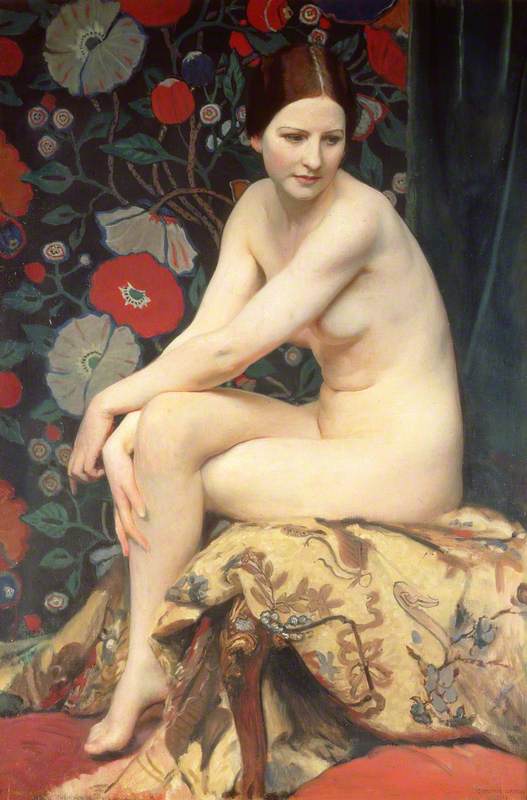

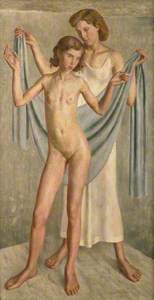

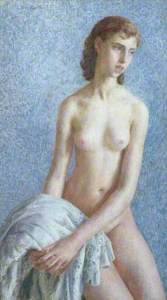

Quietly modern, and not a skyscraper in sight – Jean Cocteau would have approved. But it wasn't just Cocteau. The same year Procter produced Early Morning, Newlyn, she was busy with another painting, a figurative picture demonstrating her increasing interest in enigmatic studies of solitary, monumental female subjects that had began some years earlier with Lilian and Girl in Blue (both can be seen at the top of this piece).

With its humble origins – the model for this new painting was a local fisherman's daughter – it is somewhat surprising that the ambiguously titled Morning was to launch Dod Procter to international fame.

Its reception, exhibited in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of 1927, was uproarious. International critics singled it out as the most arresting work in the show; it was sent on tour around 23 British cities and two ocean liners; most famously, the Daily Mail bought it as soon as the exhibition opened and bequeathed it to the Tate, grandiosely proclaiming it a 'Gift to the Nation'.

Even Procter's fellow Newlyn painters recognised that there was something different about Morning. Laura and Harold Knight both recorded their startled reactions to seeing it looking decidedly out of place in Procter's primitive studio, bleakly furnished with what Procter blithely informed them was a sofa the colour of manure, while the erstwhile Newlyn resident Gluck believed Morning 'in some curious way... marked a milestone'.

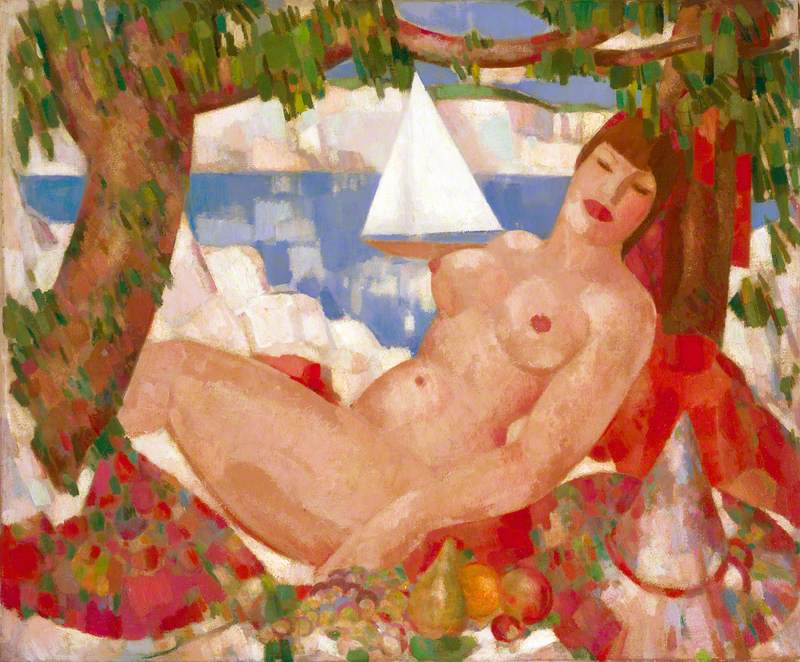

Why did this painting of a fisherman's daughter attract such rapturous praise? For one thing, there was Procter's technical skill – the same eye for tonal harmony that makes Early Morning, Newlyn so pleasing is married to a virtuosic translation of the human form into something monumental, sculptural, and timeless. The scene is at once vividly immediate and tantalisingly ethereal, the atmosphere intriguingly ambiguous. The fact it was sent out on tour, however, indicates that Morning was not understood merely as an impressive technical exercise but as something more important. Perhaps owing to its parochial origins, Morning's success hasn't been understood in what I would argue is its natural context, that of the long road back to classical beauty being walked by the major European painters of the day.

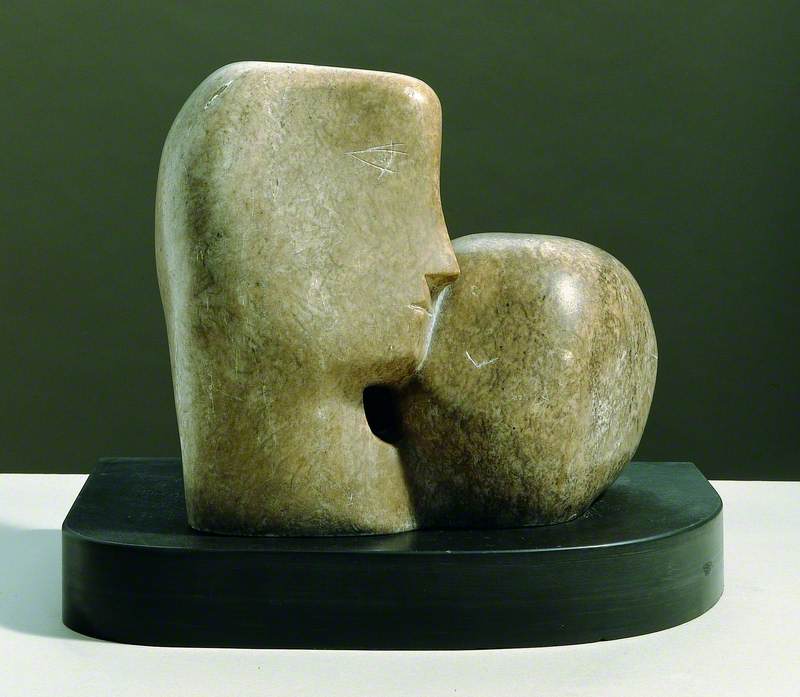

Invoking mythical memories of ancient Greece and Rome, classicism became the natural language for artists who wished not only to stress continuity with the glory of their predecessors in the face of the senseless devastation of the First World War but to optimistically look to a utopian future of stability and peace modelled on classical civilisation. Classical bodies – unfractured, stable, monumental – became talismanic images of reconstruction, the hopes of a continent inscribed in the heroic muscles of male nudes and in chaste, placid female figures who were by turns comfortingly maternal or promisingly youthful.

In this context Morning becomes a deeply evocative title, abounding with connotations of a new world to be discovered when the sleeping girl is awoken by the light she bathes in, a light that lends to her skin the quality of marble. The figure takes on a life of its own far beyond its quotidian origins, touring the provinces of England as a symbol that the country could forget the cultural pessimism that saw the War as the ruination of all claims to civility and rationalism. The tonal ambiguity of Procter's portraits is perhaps Morning's greatest merit, allowing the painting to function like a blank canvas on which to project dreams of a new civilisation which is just around the corner, just on the verge of dawning.

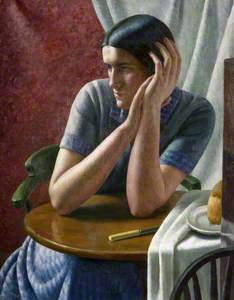

And after Morning? The succeeding years saw Procter continue in a similar mode, turning her attention towards children.

Young Roman and The Golden Girl, the former injecting an element of petulant mischief and the latter maintaining the ambiguous ethereality of her most sensitive work, attest to the continued popularity of the style.

Arguably, she strayed further into the recesses of classicism with works like the far less comforting Little Sister, approaching the adolescent nude with all the trappings of an awkward, angular, aggressively stark figure from Lucas Cranach. Perhaps the last major 'classical' work Procter produced was 1934's The Orchard, a tenderly painted image depicting a sleeping nude in an Arcadian grove.

Already, however, changes were apparent – the weight and plasticity of Procter's figures were giving way to an altogether softer and hazier approach indebted to Impressionism. In 1935 Procter's husband and fellow artist Ernest Procter died suddenly, and she never returned to the hard-edged classicism that they shared.

Despite falling out of step with artistic developments, the relatively sentimental images of children and flowers that dominated Procter's later output continued to find favour with the Royal Academy. In 1967, the Academy finally allowed women to enter its annual banquet and Dod attended, wearing a luxurious silk gown despite the fact that money was so tight that a friend remembered Dod serving her a single lettuce leaf boiled in water as 'soup' one evening.

Her response to the evening recalls the spirit of her earlier works – thoroughly, but subtly, modern. Polite throughout the meal, few would have suspected her true feelings about the venerable old boys' club. In fact, one would have to have sneaked a glance at her copy of the evening programme to do so. Presumably doodled on throughout the evening, Procter's programme features a couple of additions – firstly, an arrow marking out her position at the table amongst the male Academicians, accompanied by the word 'boredom'. Apparently this didn't get to the point quick enough. The other addition is simply the exclamation 'balls'.

Samuel Love, MA student at the University of Edinburgh