Born to a Jewish family in Vienna on 30th March 1909, Ernst Hans Josef Gombrich eventually settled in England during the Nazi regime and became one of the most eminent art historians of the twentieth century.

E. H. Gombrich's 'The Story of Art'

His 1950 book The Story of Art made art more accessible to a general audience by avoiding academic or 'pretentious' language – something which Gombrich vehemently criticised. Looking back at the book today, nearly 70 years on, it has significant limitations, despite its status as a best-seller (apparently it has sold over 7 million copies!). It is a product of its time – rarely featuring non-white or female artists. To some extent, Gombrich acknowledged the setbacks of his own book, claiming it should not be viewed as a definitive text.

With that in mind, here are ten artists and artworks on Art UK that Gombrich discussed in detail in this seminal work.

Jan van Eyck

According to Gombrich, artist Jan van Eyck (c.1380–1441) was the true 'inventor of oil painting' who defined the art of the northern European countries during the fourteenth century, creating an aesthetic which set northern artists apart from their Italian contemporaries.

He praised Van Eyck for his fantastic painterly detail, which was exemplified perfectly in this famous painting Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife (1434), which can be viewed at The National Gallery.

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife

1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

The painting shows the Italian merchant Giovanni Arnolfini and his young bride Jeanne de Chenany. Many debates as to whether she is pregnant have surrounded this portrait (though Gombrich makes no mention to this). Rather, Jeanne holds up her full-skirted dress to conform to contemporary fashions.

Gombrich interpreted Van Eyck's painting as a visual confirmation that he had witnessed their betrothal, thus making it legally binding. This may also explain why the signature reads: 'Johannes de

The mirror acts as a visual and symbolic device, to demonstrate both the artist and viewer as witnesses to the young couple's marriage.

Frans Hals

Frans Hals (c.1581–1666) was in Gombrich's opinion the 'first outstanding master of free Holland'. Hals was raised in the Protestant Dutch city of Haarlem and eventually became one of the most prolific painters in Holland. His most famous painting is The Laughing Cavalier (1624).

In this well-known portrait of the Dutch cloth merchant Pieter van den Broecke (1585–1640) Hals demonstrated his ability to paint lively, animated faces.

Gombrich wrote: 'The portraits of Hals give us the impression that the painter has "caught" his sitter at a characteristic moment and fixed it forever on the canvas.'

Jan Steen

According to Gombrich, seventeenth-century artist Jan Steen (1626–1679) perfected the craft of painting human nature. Steen could not afford to live solely by his brush, therefore he also ran an inn, explaining why a large number of his paintings show merry festive scenes depicting the lives of peasants, like the one below. Steen was an avid observer of life, whose fascination with human behaviour was reflected in every detail of his works.

In this painting, now in The Wallace Collection, we observe a Christening feast. Gombrich notes that friends and relations stand around the father of the baby, who proudly holds his child. Gombrich particularly appreciated Steen's figure of the woman in the foreground, for its harmonious arrangement of colours.

Jean-Antoine Watteau

Gombrich thought that French artist Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) enriched the imaginations of his viewers by capturing the essence of frivolity and graceful gallantry that came to define mid-to-late eighteenth-century France – and the lives of its indulgent aristocracy before the French Revolution in 1789.

Fête galante in a Wooded Landscape

c.1719–1721

Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

Paintings such as Fête

Gombrich dismissed those who criticised Watteau's art for merely being a depiction of eighteenth-century aristocratic tastes and frivolous fashions. Instead, he regarded Watteau as one of the greatest painters of his time, whose idealised, rose-tinted paintings moulded the genre we call today Rococo.

William Hogarth

In many eyes, William Hogarth (1697–1764) defines eighteenth-century England through his didactic and satirical engravings and paintings. In Gombrich's view, Hogarth was trying to teach his audiences about 'the rewards and virtues of sin.'

In his series The Rake's Progress, Hogarth visually narrated the downward and inevitable spiral of an idle 'rake' (a gentleman who is usually a hedonist, a womaniser with immoral conduct), whose terrible life decisions result in a life cut tragically short.

In this scene, the rake collapses in Bedlam, as he lies on his deathbed (a dirty floor in the middle of an asylum). The only person visibly mourning his death is the weeping servant girl behind him.

According to Gombrich, Hogarth would have compared his profession to the art of a playwright. His motivation was to capture the 'character' of each protagonist. Each of his paintings sets a scene that propels a larger, theatrical narrative, which often becomes rather sordid, scandalous and tragic. Gombrich argues that while Hogarth was trying to establish a new art form, he was also referring back to artists of the past, like Jan Steen, who also painted scenes of social merriment and debauchery.

Joshua Reynolds

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) was a prolific eighteenth-century portrait painter who became the first president of the newly founded Royal Academy when it opened in 1768. In many ways, Reynolds came to embody the art establishment of his time.

Unlike Hogarth, who tried to create a new kind of 'English art', Reynolds preferred to revere the Italian masters, travelling to Italy to study the paintings of Raphael, Titian and Michelangelo.

Gombrich describes Reynolds as an artist deeply concerned with 'taste', which in the context of the eighteenth century was a term not only designated to aesthetics but also implied high moral virtues, intellect and ultimately status.

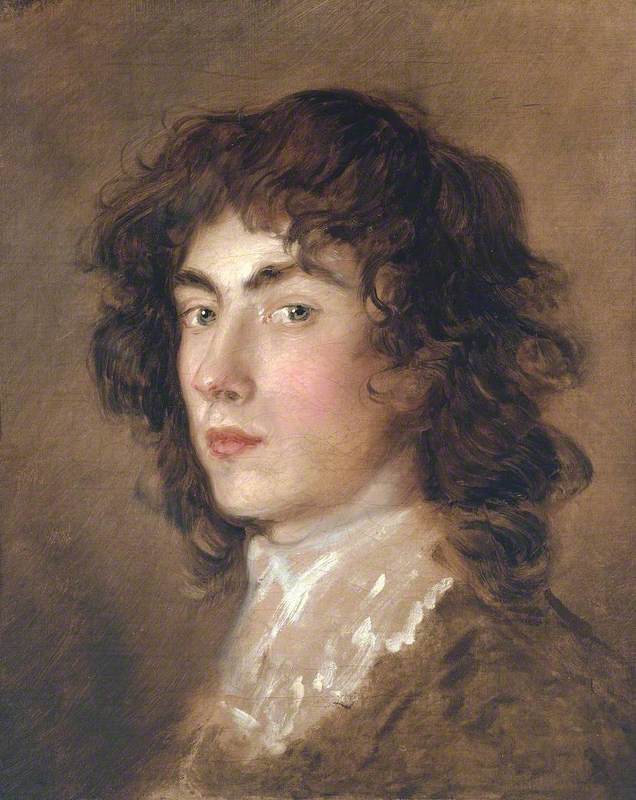

Thomas Gainsborough

In comparison to Reynolds, Gombrich describes rival painter Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) as a 'self-made man' who achieved great success despite never travelling to Italy to learn from the masters.

Unlike Reynolds, Gainsborough was less concerned with being 'highbrow'. His talents lay in his ability to show a sense of movement through his brushwork, a refined touch and a fresh take on his subject matter.

In the portrait Miss Elizabeth Haverfield (c.1780), Gombrich praises the artist's capturing of the child's fresh complexion, as well as the detail showing the shining material of her cape. According to Gombrich, while Reynolds style was laboured, Gainsborough's work offered exquisite detail and texture.

J. M. W. Turner

J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) spent the first half of his life trying to surpass the landscapes of French painter Claude Lorrain. This painting by Turner is an imitation of Lorrain's famous seaport paintings, which are very similar compositionally to those of Turner.

Dido building Carthage, or The Rise of the Carthaginian Empire

1815

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Turner was a favourite at the Royal Academy until his work started to become more daring and abstract, exemplified in this painting below.

Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth

exhibited 1842

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Writing on Turner's Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth (exhibited 1842), Gombrich wrote: 'We almost feel the rush of the wind and the impact of the waves. We have no time to look for details. They are swallowed up by the dazzling light and the dark shadows of the storm cloud.'

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) was an American artist who emigrated first to Russia and then to England in the mid-nineteenth century.

Averse to sentimental subject matter popular at the time, Whistler according to Gombrich was primarily concerned with colour and form, the former of which was often characteristically sombre and subdued in his work.

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge

c.1872–5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

In The Story of Art, Gombrich discusses Whistler's controversial painting Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge which ruffled the feathers of art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) and created a public debate over aesthetics and what constituted a 'finished' work of art.

Käthe Kollwitz

Rather shockingly (though perhaps unsurprisingly for the mid-twentieth century), Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) is the only female artist Gombrich includes in his gigantic 650-page book.

He praised Kollwitz for her earnest and politicised art, which intended to champion the causes of the poorest, most downtrodden members of society. As seen in this etching from 1903, Kollwitz's work often featured the motif of the dying child as a way to stimulate compassion in her viewers.

In Gombrich's view, the greatness of Kollwitz's work lied in the fact that her lithographs, woodcuts and etchings portrayed a harsh reality, trying neither to idealise or romanticise the undignified situation of the labourer. For this reason, Gombrich claims her work was favoured far more in Eastern Europe, under Communist regimes than in the west.

On that note, we will leave you with this quote by Gombrich, from the final chapter of the book:

'Our knowledge of history is always incomplete. There are always new facts to be discovered which may change our image of the past.'

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK