The story of Harold Knight (1874–1961) is an unusual one in art history: he has been vastly overshadowed by his wife and female counterpart, Laura Knight (1877–1970).

Laura Knight – the first woman to be elected a full member of the Royal Academy – broke gender barriers with her female-gaze-focused paintings of women. In contrast, Harold Knight's portraits of both sexes have been considered skilful but traditional, resulting in his status as a largely forgotten British artist. But, if we take a closer look at his work, could we also discover a more subversive side to this painter?

Laura Knight; Harold Knight

1937, bromide print by Associated Press

Born in Nottingham, the son of an architect, Harold Knight studied at Nottingham School of Art, which was considered one of the best of the English provincial art schools during the mid-1890s. It was here that he met Laura (then Laura Johnson), a fellow student whom he painted in a tender early portrait in 1891. Laura later reflected that it was while sitting for this painting that she 'first got a hint that I meant as much to him as he to me'. She was right, as by 1903 the pair got married.

When Laura first met Harold, he was Nottingham's star student, winning numerous prizes for his paintings, including a series of oil studies of male nudes. He also spent a year in Paris, studying at the progressive art school Académie Julian, where he focused on drawing from a live model – an essential part of artistic training for male artists during the nineteenth century.

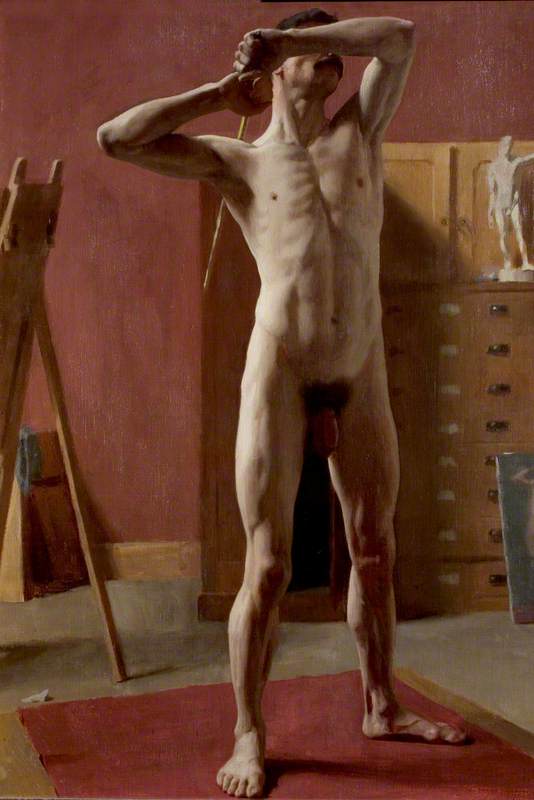

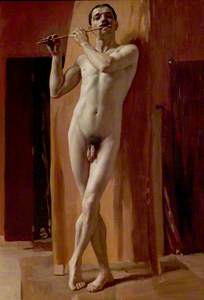

Highly accomplished paintings by Harold Knight, such as Standing Male Nude, are typical of academic nude studies, in which male models resemble the marble heroes of Ancient Greece. Much like his fellow painters Eugène Delacroix and Pascal Adolphe Jean Dagnan-Bouveret, Knight has depicted his model standing in a set pose, derived from classical sculpture.

Knight's figure has his arms raised and bent as he clasps a stick angled behind his back. The device of models holding such a stage prop allowed for artists to focus on the portrayal of tensed muscles, taut contours and anatomical detail. With the witty inclusion of an easel, a small plaster figure and a half-seen painting of a nude, Knight points out that this scene has been constructed in a studio, within which his depiction of the model conforms to the trope of the academic nude.

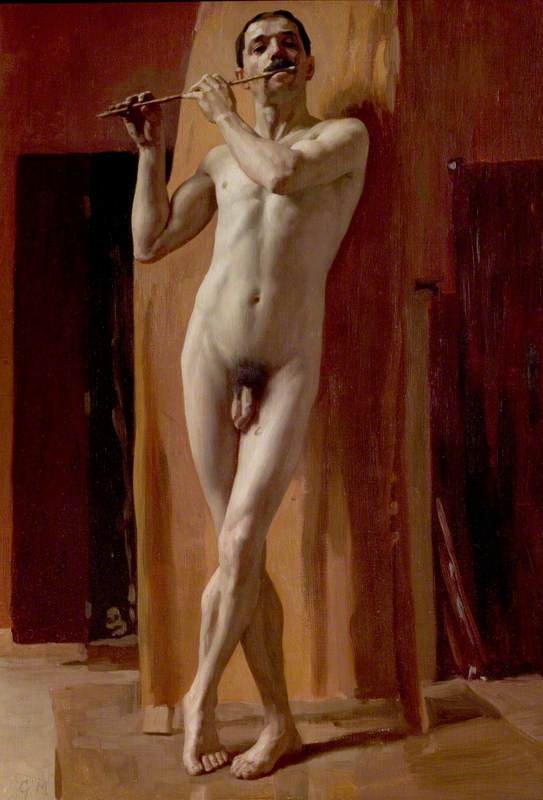

However, another painting by Harold Knight demonstrates a more individual approach to rendering the male nude. In Standing Male Nude from 1895, the full-frontal model holds a stick but, instead of holding it as a staff, pretends to play it like a flute. Moreover, crossing his legs, with one foot on tiptoe, the man adopts a theatrical stance. Not quite the dominant, muscular figure one might expect from the period, Knight's model instead appears in a more expressive, playful and unconventional pose.

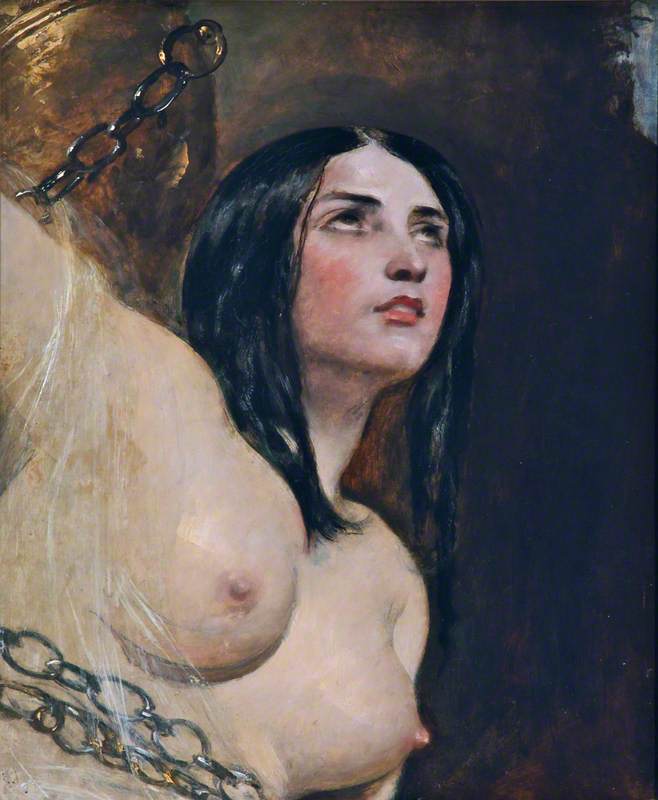

This work parallels paintings by British artist William Etty, who is best known for rendering soft, fleshy nudes in intimate, vulnerable poses such as the figure in Man with an Arrow. Some art historians have noted that his erotically charged male nudes are open to queer readings. Similarly, there's an intimacy and sensuality at play in Knight's painting, which quietly unsettles the convention of the powerful academic pose and offers up an alternative form of masculinity.

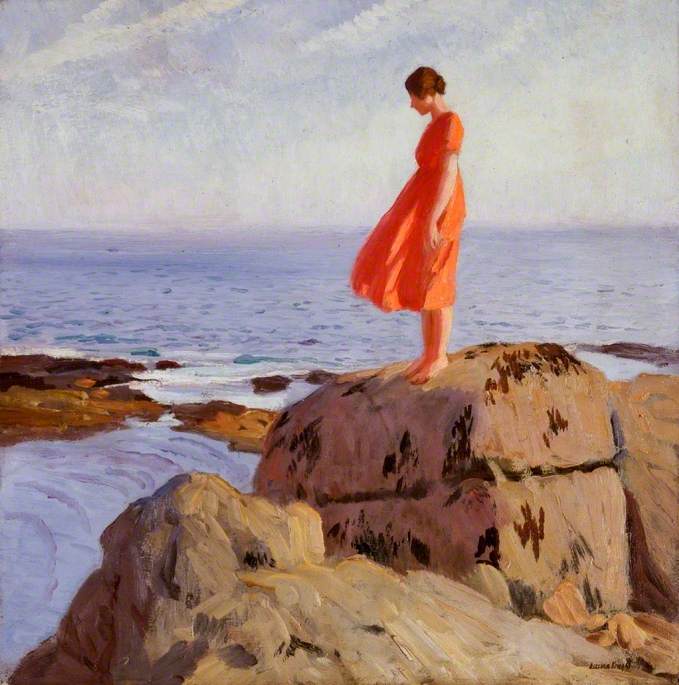

While Knight turned his gaze on naked male bodies, the women in his paintings keep their clothes on. By the turn of the twentieth century, avant-garde British artists such as Walter Sickert were painting the female nude. Even Harold Knight's wife Laura had taken this as her subject, undressing dancers backstage at the theatre. In contrast, Harold Knight's fully clad female figures are seen absorbed in activities such as reading, writing and sewing in the home.

Harold Knight's paintings of women in domestic spaces demonstrate his interest in Dutch interior paintings. With his wife, he spent several years in Holland, visiting the artist colony in Laren and studying the Dutch masters, including Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer. In works such as Sewing, the influence of Vermeer is evident: sunlight streams through the window to illuminate the scene and cast soft shadows on the face of a woman sewing.

Ethel Bartlett (1896–1978), Pianist

c.1935

Harold Knight (1874–1961)

Harold and Laura shared models, many of whom became close friends with the couple. Harold Knight's portrait of Ethel Bartlett from around 1935 represents one favoured sitter, the renowned English pianist. The artist has cleverly centred his composition around the musician's hands, which she clasps prominently in front of her.

In another painting of Bartlett from c.1937, Harold Knight portrays the pianist reclining and caught deep in thought, gazing beyond the picture frame. Once again, he has focused his attention on the pianist's hands and splayed fingers, which she wraps around her chest. Enhanced by a golden light which makes Bartlett glow, it's a sensual rather than sexual image of an introspective female figure.

A Young Woman standing at a Virginal

about 1670-2

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675)

The defining tranquillity of Harold Knight's portraits, as well as showing the influence of Vermeer, point to Knight's personality: unlike his gregarious wife, the painter was known for his introverted character and gentle nature. He was also known to be somewhat subordinate to Laura, who was the one to propose. One of the couple's models and a fellow artist, Eileen Mayo, later reflected on the couple's relationship, stating that Harold was a 'good wife' to Laura.

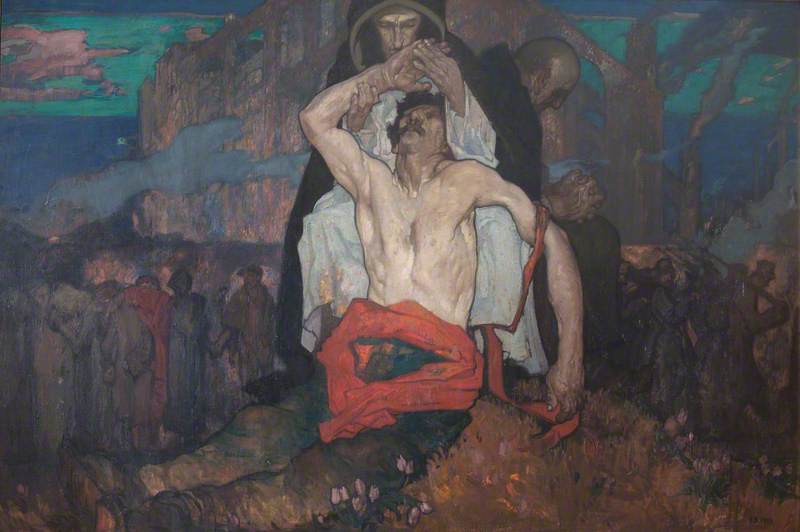

Led by his solid principles, in art and life, Knight made a bold and difficult decision in 1916. At the outbreak of the First World War, military service was announced as compulsory for all single British men. Knight joined an absolutist minority who refused to fight; he declared himself a conscientious objector, resisting combat on the grounds of pacifism.

Conscientious objectors, seen to have rejected conventional British society and everything it stood for, were required to work as labourers during the war. By this time Knight was living in Cornwall, where he and his wife had joined the Newlyn School of artists. Now, forced to work as a farm labourer on the Cornish coast, he found himself alienated by friends and colleagues, writing: 'I have lost the friendship of several people whose friendship I valued, and my career as a portrait painter has been prejudiced by my attitude towards the war I have been compelled to take.'

Knight's decision put a strain on both his physical and mental health, which didn't go unnoticed by his wife. 'Hoeing', she remarked, 'for days on end without seeing a living soul. He was again a sick man.' By 1917, Knight's health had deteriorated to such an extent that he was excused from further labour and returned to painting on a full-time basis.

Knight was not the only British artist to become a conscientious objector, joining celebrated Bloomsbury group members Mark Gertler and Duncan Grant. These men turned to creativity to express their refusal to support Britain's involvement in the war; by painting domestic interiors they conveyed their staunch refusal to cooperate in battle.

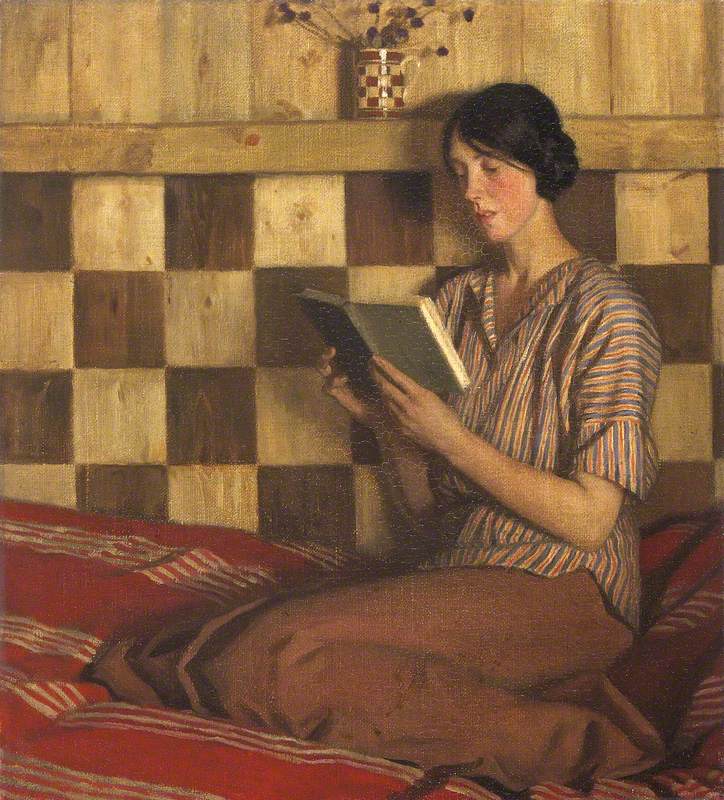

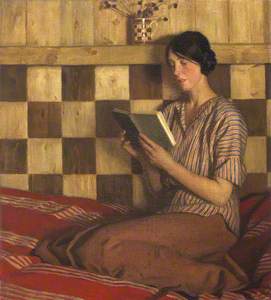

A pacifist stance is also discernible in Harold Knight's interiors from this period, in which women engage in contemplative activity, far removed from any sort of conflict. In The Green Book, an integral sense of calm surrounds the sitter, created through harmonious patterning in the room's chequered décor and striped furnishings, which match the model's clothing. Knight's paintings can be read as quietly subversive statements in support of his status as a conscientious objector.

When the war ended, Harold and Laura Knight moved to London, although they frequently spent summers painting in Cornwall. Despite the social ostracism he experienced as a conscientious objector, Knight enjoyed professional success in his lifetime, exhibiting his portraits at galleries including the Royal Academy. In 1937, one year after Laura Knight was elected to the Royal Academy, Harold Knight became a Royal Academician. Between 1936 and 1945, he was also President of Nottingham Society of Artists.

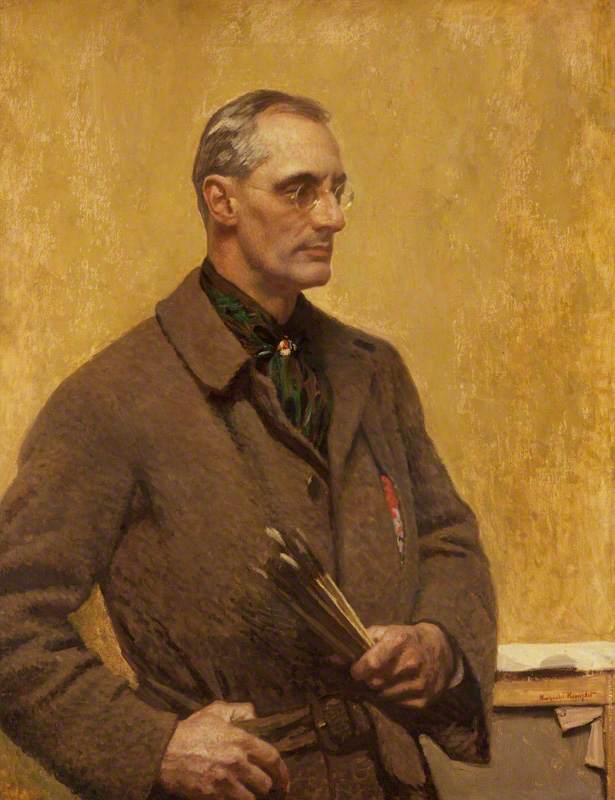

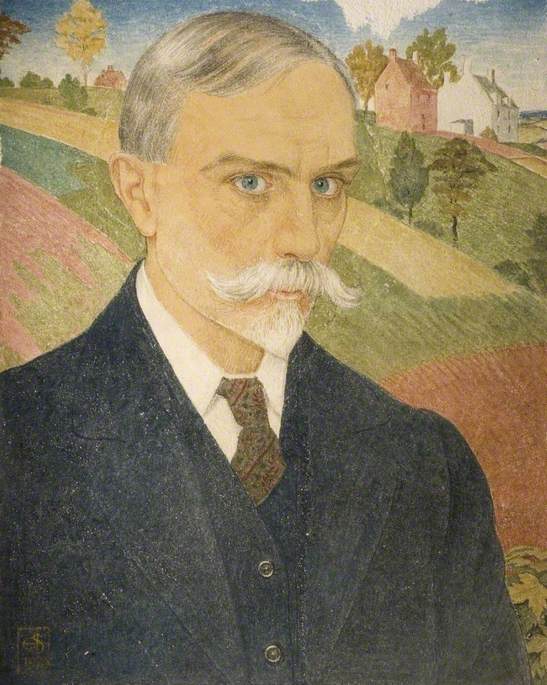

In a compelling self-portrait from around 1923, Knight represented himself with confidence: standing straight, he grips his belt with one hand and holds an assortment of paintbrushes with the other. The poise in Knight's self-portrait also points to the fact that, from the very start of his career, Knight was assertive in his personal and artistic choices: he stood by his unconventional wife, turned his male gaze on nude men and positioned his female subjects as champions of peace. A pacifist painter, Harold Knight put up a fight through his art.

Ruth Millington, art critic and writer

Further reading

Kenneth McConkey and Anna Gruetzner Robins, Impressionism in Britain, Exhibition Catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery and Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, 1995

Barbara C. Morden, Laura Knight: A Life, McNidder & Grace, 2013

James Russell, In Relation: Nine Couples who Transformed Modern British Art, Sansom & Co., 2018

Timothy Wilcox, 'Laura and Harold Knight in the First World War', The Burlington Magazine, 157 (1350), pp. 602–609, 2015