In September 2019, a nomadic artist dressed head to toe in indigo inhabited The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This figure, incongruous with the steady stream of tourists, carried with him a weighty bundle of Egyptian linen and a battered suitcase filled with his ammunition: an array of chunky oil pastels.

Over the course of nine days, the linen was unravelled, rolled up and moved from department to department. In the museum's Temple of Dendur, hoisted up onto supports, it became simultaneously a canopy for the artist and an expansive canvas, upon which developed a landscape of dappled clouds. Across the museum, this itinerant and his image morphed: the artist wore an ornate gown, a red bodysuit and toyed with a mask, while all the while earthy mountains and smooth water emerged.

Lands, Waters, Skies

2019–2020, installation/performance by Nikhil Chopra (b.1974), artist-in-residence at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Nikhil Chopra was the Indian performance artist for whom the museum became a home. Sleeping, eating and drinking in this hallowed Upper East Side space, amidst histories of creativity, provided a new context for his longstanding practice of live-documenting landscapes. This is a decolonising process in part, linked to art's history as a form of cultural and geographical reportage. A selection of Art UK's images exemplify this type of descriptive art, typical of colonial practices where works were enmeshments of landscape documentation and political ambition.

India's Himalayan valleys, subject of Chopra's recent show at Mumbai gallery Chatterjee Lal, are a site privy to colonial representational regimes: a place encountered and realistically depicted to help a particular perspective and memory to stake its claim to truth. Aspects of Chopra's characters are derivative of the traveller-explorer persona aligned with these colonial pursuits. And in his actions, he mimics their practices.

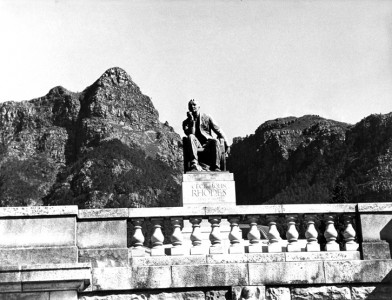

His footsteps follow those of British artists Thomas and William Daniell, an uncle-and-nephew team who went to make their money and reputation documenting India in the early nineteenth century, satiating a voracious imperial appetite for seeing the reaches of the Empire. They were the first artists to be given permission to work in India by the East India Company, and their seemingly innocuous landscapes were read and revered in Britain as the products of intrepid journeys, earning Thomas the sobriquet 'artist-adventurer'.

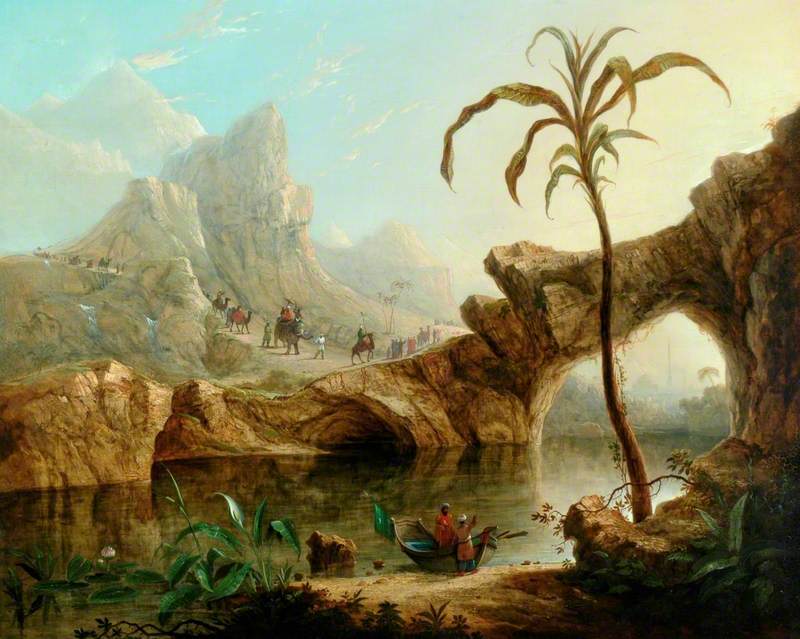

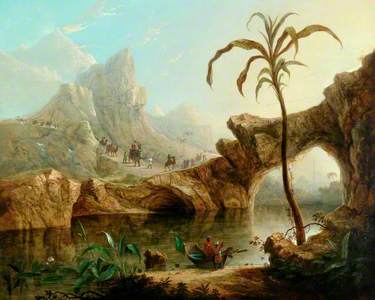

Rope Bridge Over the Alakananda River at Srinagar, Garhwal

1808

Thomas Daniell (1749–1840)

Daniell's 1808 Rope Bridge Over the Alakananda River at Srinagar, Garhwal was, for audiences at the time, testimony to the artists' heroism. The detailed picturesque image conveyed a glorified idea of their traipses across mountain passes, around lakes and through remote villages. With tools in tow, and a camera-obscura and perambulator – possibly carried by assistants – a faithful representation emerged of the moment when the city's Rajah and his people effected their escape from an incoming invasion.

But there was more to this image. The artists were harvesting data. As the length of land was measured, easel was erected and pencil struck canvas, the landscape was being enumerated: an exercise in knowledge production and acquisition was underway. This 'scientific accuracy' was very much used as a sales pitch and part of the work's value lay in the accompanying description of the:

'affecting scene, a most melancholy example of the wretched state of society under these petty chieftains, whose views of government are little better than those of savages.'

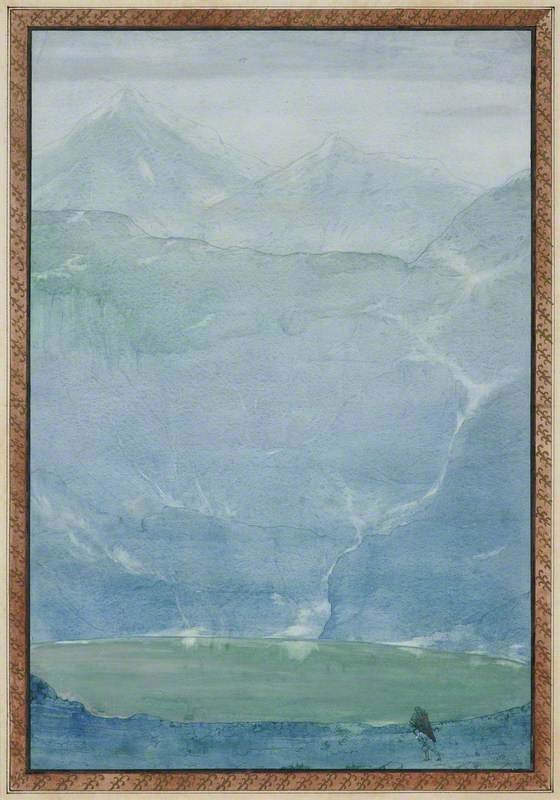

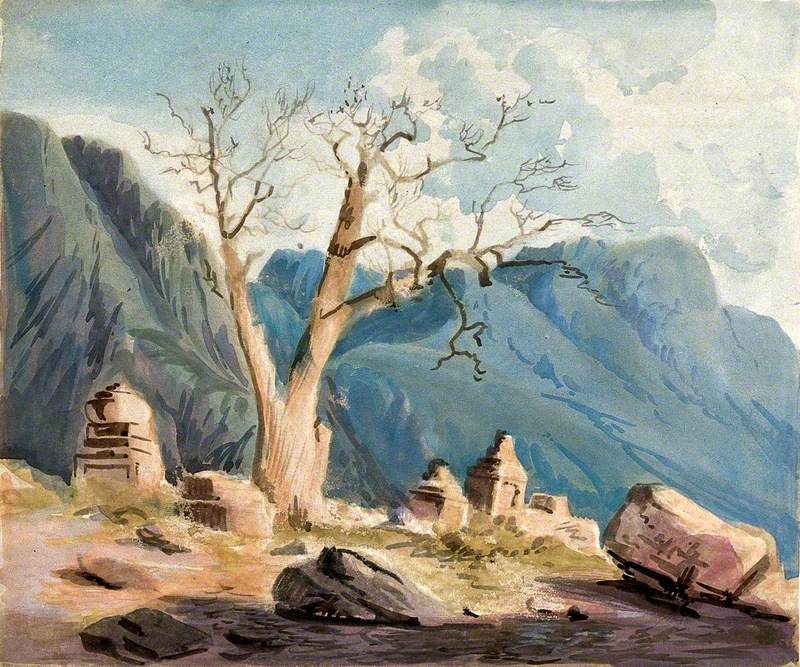

Old Poplar Tree (Populus Euphrasica) with Stone Monuments in Ladák, Kashmir

1854–1858

Hermann von Schlagintweit-Sakünlünski (1826–1882)

Old Poplar Tree (Populus Euphrasica) with Stone Monuments in Ladák, Kashmir is similarly a loaded image and a vestige of exploration and colonial discovery. Its author, Hermann von Schlagintweit-Sakünlünski, and his brother, Robert, had their trip to India between 1854 and 1857 commissioned by the East India Company and the King of Prussia, following a recommendation from the polymath Alexander von Humboldt.

Rooted in scientific investigation, the compulsion to gain a detailed picture of the world and to complete a magnetic survey of the country led the brothers to travel more extensively than anyone before in the Western Himalayas, whilst seemingly measuring and collecting everything that was there.

This image was one of 749 representations made on the trip and joined the 340 crates worth of material which were shipped home to bear witness to their interrogation.

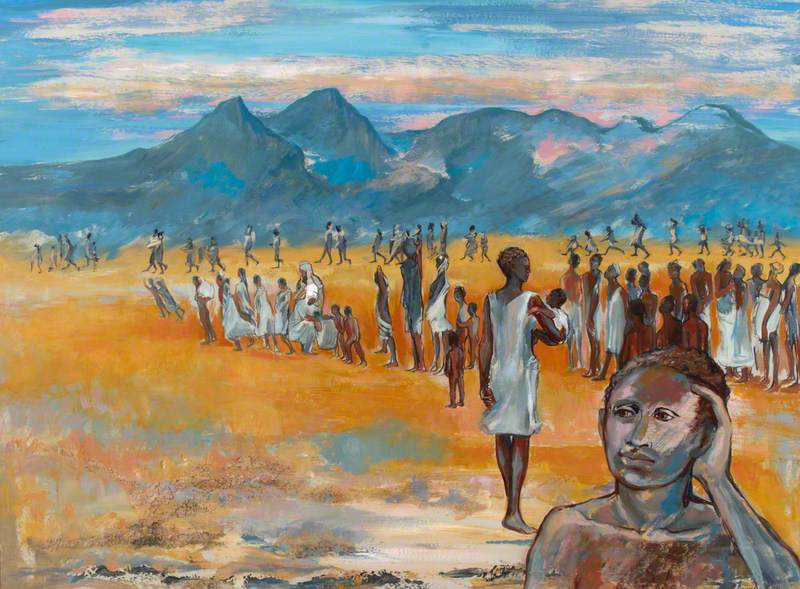

It was this laying claim to the environment, collect-and-scrutinise attitude which motivated Samuel Fyzee-Rahamin and underpins his image Ali Pathar, Kashmir.

An artist, novelist and playwright, Fyzee-Rahamin was well versed in establishment values and aesthetics, having been taught at the Royal Academy by tutors including John Singer Sargent in the early twentieth century, beginning his career as a successful portrait painter. Spurred on by Gandhi's ideals, on his return to India in 1908 he eschewed naturalism to revive Rajput miniature painting and became a vocal proponent of Indian idealism.

The image rebalances the landscape, presenting a softened depiction of Kashmir with room for imagination. Pools of colour form the mountainous scene with a single figure foregrounded. This work, similar to Chopra's practice, could well be a correcting of the colonial gaze, which, as shown, so emphatically articulated itself across India.

Cleo Roberts, art historian