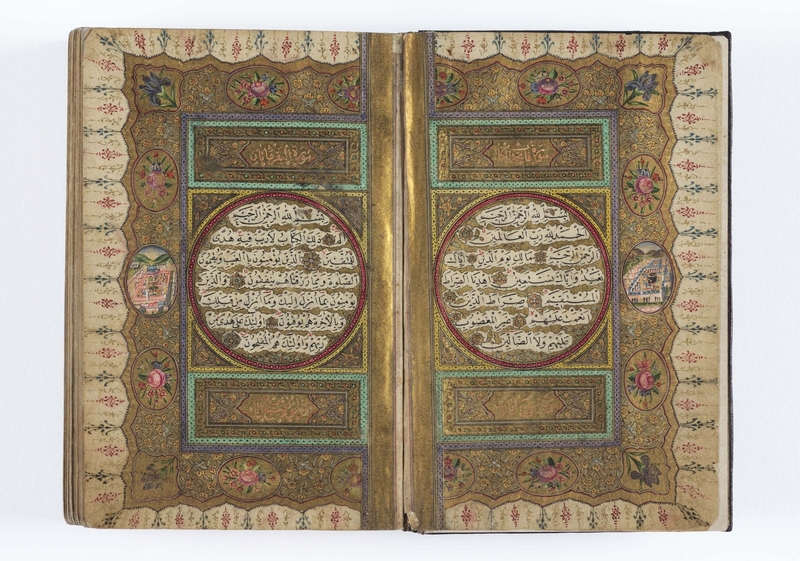

In August 1716, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and her husband, the newly appointed British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, set off from London for Constantinople, modern-day Istanbul. The journey across Europe took several months; between 1717 and 1718 they lived in a house in Pera, a cosmopolitan district on the European shore of the city.

The letters Lady Mary wrote to her friends in England during this period give us some of the most evocative descriptions in the English language of early eighteenth-century Istanbul, when the Ottoman Empire still retained much of the wealth and cultural diversity of its zenith in the previous century.

A European Ambassador in the Second Court of the Topkapi Palace

c.1740

Antonio Guardi (1699–1760) (and studio)

It is obvious from Lady Mary's correspondence that she would have made a far more successful diplomat than her husband, who was recalled to London after only a year (the couple stayed on an extra year anyway). She made the most of her privilege as a woman to access the nuclei of Ottoman life, braving the steamy nudity of the hamam and learning Turkish by infiltrating the harem (women's quarters) of Topkapi Palace, where she befriended the women closest to Sultan Ahmed III and learnt about political machinations hidden from her husband.

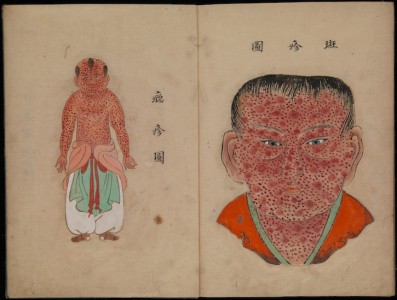

However, her greatest achievement – and one for which history has not sufficiently rewarded her – was in the field of medicine. In 1717 she wrote to a friend about the Ottoman practice of smallpox inoculation – called 'variolation' – long before the procedure was known about in Europe:

'The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless by the invention of ingrafting, which is the term they give it. There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated... the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch), and puts into the vein as much matter as can lye upon the head of her needle, and after that binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell.' – Letter from Lady Montagu to Mrs S. C., Adrianople, 1st April 1717.

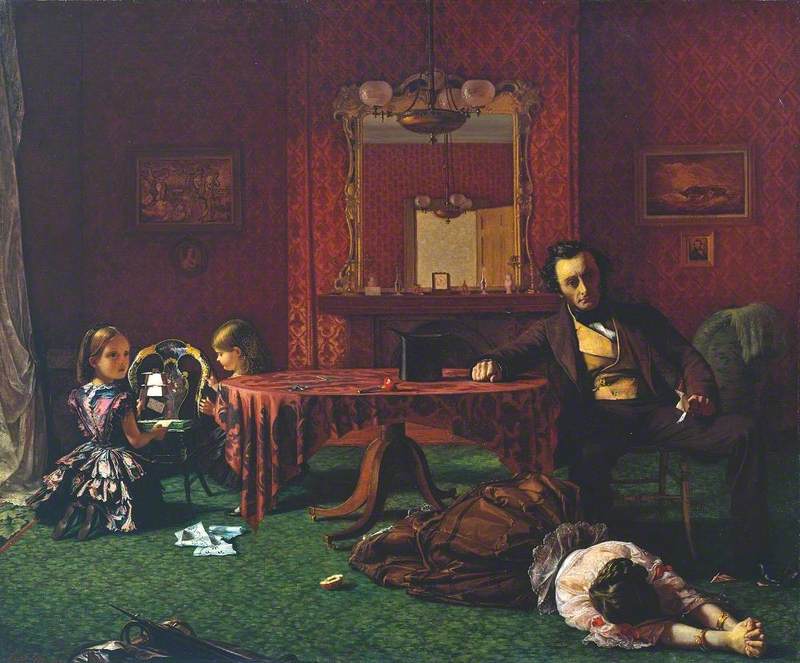

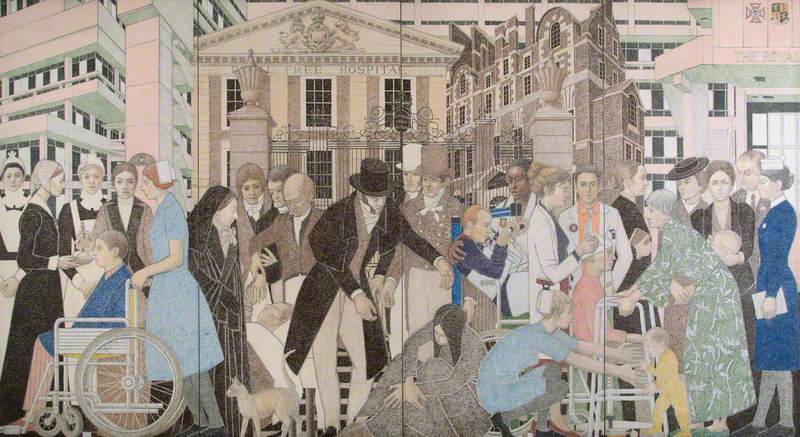

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu with her son, Edward Wortley Montagu, and attendants

c.1717

Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (1671–1737) (attributed to)

Lady Mary herself had suffered smallpox two years earlier, which had left her with scars; her brother had been killed during the same epidemic. No doubt with this in mind, she persuaded the British Embassy's doctor, Charles Maitland, to carry out what must have seemed like an alarmingly primitive process on her four-year-old son, Edward (seen in the painting above with his mother).

The procedure proved successful, as you can see from this much later portrait of Edward, who went on to become a traveller in his own right (he left England permanently in 1762 and travelled in the Middle East as an enthusiastic archaeologist, eventually settling in Venice in 1773).

After returning to London in 1718, Lady Mary was eager to introduce the method to English doctors, who were at first highly sceptical, even after Lady Mary demonstrated it successfully on her remaining uninoculated child, her daughter Mary (who had been born in Istanbul), in April 1721. She garnered some attention for this, after making efforts to publicise the event (and after persuading Newgate Prison authorities to test the procedure on seven (un)lucky prisoners), but has still been passed over in the history books in favour of the British doctor Edward Jenner, who is considered the 'father of immunology' – despite having popularised the process of vaccination nearly eighty years after Montagu first made the theory known in England.

Even today, few know of her contributions to the field of immunology. The NHS website has a page devoted to the 'history of vaccination', which states that: '[in the 1700s] variolation eventually spread to Turkey, and arrived in England in the early 18th century.' In 1796 'British physician Dr Edward Jenner discovered vaccination in its modern form and proved to the scientific community that it worked.' According to this official website, variolation arrived like some kind of immaculate conception in Britain before a man took the credit many years later – plus ça change.

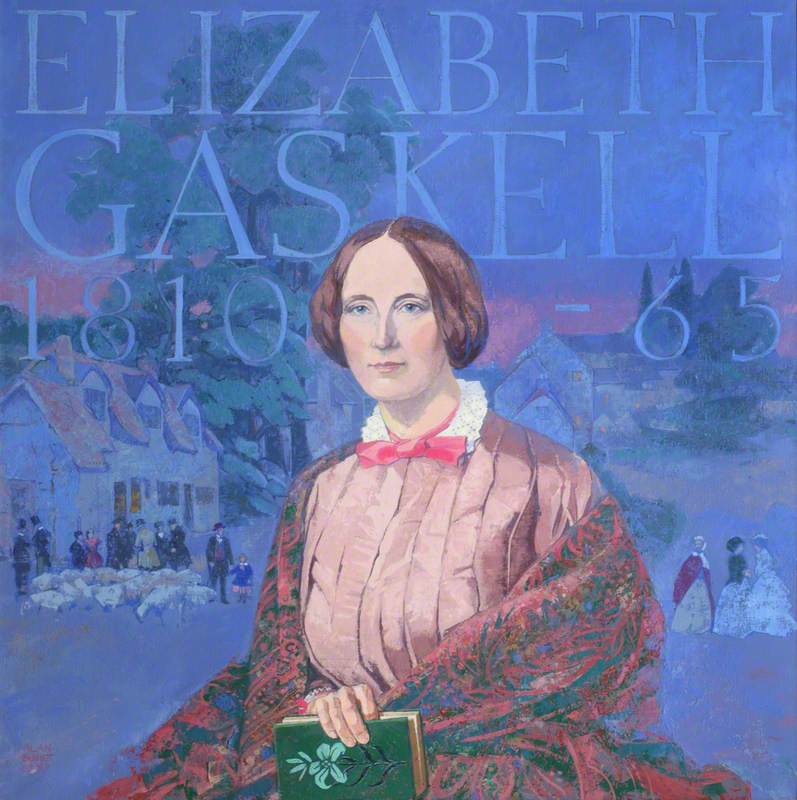

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), Writer and Traveller

1739

Carlo Francesco Rusca (1696–1769)

Fortunately, the paintings above, and Lady Mary's letters, help us recognise the pioneering role she had in developing the process of vaccination that has saved tens of millions of lives in the past two centuries.

Alev Scott is the author of Ottoman Odyssey, published by Riverrun