One of the many rare gifts of Art UK is its inspirational capacity for allowing great paintings back into the light. On one level, of course, a work of art does not actually change when it is reattributed to its creator, but it does tend to get a lot more scrutiny (not all of the 200,000-plus paintings on the website can hope to receive equal attention, nor should they).

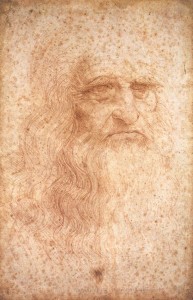

Recently, I joined Bendor Grosvenor on an episode of the BBC Four programme Britain's Lost Masterpieces on his quest to work out who painted a portrait of a bearded physician hanging above a door at Tatton Park, a National Trust property in Cheshire.

Realdo Matteo Colombo (1515–1559)

1530–1569

Francesco Salviati (1510–1563)

It was brought to London for cleaning and restoration, which only seemed to confirm its considerable artistic quality. Bendor pretty rapidly abandoned his initial notion that it might be by Parmigianino (1503–1540), and came to the conclusion that it was by his slightly younger near-contemporary, Francesco Salviati (1510–1563), and furthermore that the sitter was a celebrated surgeon and professor of anatomy called Realdo Colombo (c.1515–1559). Reassuringly, since the airing of the programme in February 2021, authoritative expert voices have supported the work's attribution to Salviati.

There is no denying that in the grand scheme of things Parmigianino is a bigger cheese than Salviati, but in another sense – and especially in the context of UK public collections – Salviati's authorship arguably only increases the interest and value of the discovery. The reason is simple: there are six oil paintings by Parmigianino in British museums (three in The National Gallery, two at the Courtauld Gallery, and one in York Art Gallery), as against a pre-Bendor grand total of zero by Salviati.

What is more, to the best of my knowledge, there are also none hidden away in UK private collections which might in due course make their way into public collections.

On the programme, Bendor employed the term 'Mannerism' with reference to the artistic style of such figures as Parmigianino and Salviati, and the rest of this piece will be devoted to attempting to explain both what people are trying to capture when they use it, and also why I react to it in more or less the same way as vampires – at least in old horror movies – respond to daylight.

The extent of my aversion is indicated by the fact that, when I published a 300-page book on Parmigianino in 2006, the word Mannerism did not get a look-in, even in the context of some sort of denial of its usefulness.

Raphael died in 1520 at the tragically young age of 37. His art had never stood still, and it is hard to doubt that his most faultlessly classically balanced achievements – above all in his frescoes in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican – were behind him. His last altarpiece, the Transfiguration – also in the Vatican – appears to have been completed by his pupils, the most notable of whom was Giulio Romano.

View this post on Instagram

The energetic, theatrical poses of the figures in its bottom half, together with its delight in dramatic contrasts between light and dark zones, certainly propose a very different visual universe.

One of my teachers, John Shearman, wrote a superb short book simply titled Mannerism, which was first published in 1967 in a Penguin series called 'Style and Civilisation'. In it, he defined Mannerism as 'the stylish style', and that aspect of the art of the period from 1520 to 1550 and beyond is perfectly reflected in the paintings of Parmigianino, and indeed others.

View this post on Instagram

The problem is that such savagely explosive works as Giulio Romano's illusionistic fresco of the Fall of the Giants in the Palazzo Te in Mantua or Rosso Fiorentino's Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro in the Uffizi in Florence, to name but two of the most extreme, cannot possibly be accommodated within Shearman's stylish style.

Returning to Parmigianino, I suspect one of the reasons Bendor initially thought of his name was that he is such a wonderful portraitist. Both York Art Gallery and The National Gallery have outstanding examples. The National Gallery's Portrait of a Collector represents a peculiarly compelling blend of realistic observation – you feel sure you would know this man again if he sat opposite you on the tube – and almost neurotic menace.

Conversely, in his religious pictures, Parmigianino delights in distorting both the human form and space. These effects are memorably apparent in his Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, also in The National Gallery, where the main action is framed in the foreground by a dramatically bearded old man in profile who fills the bottom left-hand corner of the panel, and in the background by a couple of diminutive aged figures seen against the light of a window in a room beyond.

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine

about 1527-31

Parmigianino (1503–1540)

Perhaps even more thrilling is an unfinished Virgin and Child from the Courtauld collection, which is currently on long-term loan to The National Gallery, where one has an almost uniquely intimate sense of looking over the artist's shoulder in mid-stream.

Interestingly, the style is not that of his final years – like Raphael, he too died far too young at the age of 37 – but Parmigianino was absolutely not a nine-to-fiveish regular guy, and must simply have abandoned this gorgeous invention in the late 1520s.

The National Gallery also houses another almost pervertedly stylish – and stylised – monument to this particular strain of mid-sixteenth-century Italian artifice in the form of Bronzino's An Allegory with Venus and Cupid.

An Allegory with Venus and Cupid

about 1545

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572)

Long ago this extraordinary painting enjoyed a distinctly quirky reputation as the source of the squashing foot that was a recurring motif in Terry Gilliam's animations on Monty Python's Flying Circus, but that is not why it still compels attention. Rather it is its gleeful elongation of the human figures and theatrical compression of the narrow world they inhabit that make it so memorable.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

1523–1524

Parmigianino (1503–1540)

If we had asked Parmigianino or Salviati what it felt like being a Mannerist artist, they would have been utterly baffled, because it is neither a self-definition – as the labels attached to so many art movements have been – nor even a more general period term.

The Madonna and Child with Saints John the Baptist and Jerome

1526-7

Parmigianino (1503–1540)

If it is simply a catchy shorthand for post-Raphaelite, then so be it, but for me, that still does not represent much of a consolation for the way it unites extreme anti-classical violence and neurosis with the ultimate in coolly frozen elegance under a single label, when they actually seem to be polar opposites.

David Ekserdjian, Professor of History of Art and Film at the University of Leicester