The Wollaston Family

(in situ), 1730, oil on canvas by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

When what is now New Walk Museum & Art Gallery opened in 1849, Leicester Corporation became one of the first UK local authorities to run a museum. It has been part of many new initiatives since then. In 1930, for example, the City of Leicester Museums Trust was set up. This independent charity manages and administers money collected through museums donation boxes, private gifts and bequests, using the funds to purchase items for the collections. It has enabled many important acquisitions to be made in recent years. These have included a portrait of Sir David Attenborough by Bryan Organ, a 1908 Clyde motor car, a partial specimen of a Jurassic plesiosaur, a replica skeleton and vertebrae of Richard III, and a third-century Roman coin hoard.

New Walk Museum & Art Gallery

Today, the Trust is facing its biggest ever challenge. It is seeking to raise £564,528 to secure William Hogarth’s The Wollaston Family of 1730, which has been on loan to the museum since 1943 and is for sale with a deadline of 28th February 2019. This is less than 20% of the painting’s current market value, which Sotheby’s estimate as around £3,000,000. It is being offered to the nation by the Wollaston family for permanent display at New Walk Museum & Art Gallery at the reduced price of £1,468,200 in lieu of inheritance tax, an arrangement approved by The Arts Council. Of this, HMRC will accept £903,672 in tax. The balance of £564,528 must be raised in order to acquire the Hogarth for Leicester.

External funding applications are pending. The City of Leicester Museums Trust has already given £30,000, and it has also launched an appeal to raise a further £25,000 in public donations.

For details of the appeal and to make a donation, please visit www.leicester.gov.uk/hogarth

Leicester’s Hogarth was passed down through the Wollaston family and has been on show at New Walk Museum for over 75 years, delighting the public for generations. Today, up to 200,000 people a year come from across the whole UK and overseas to see one of the UK’s oldest regional museums and its artworks. These include an outstanding collection of German Expressionist art, Picasso ceramics bequeathed by Lord Richard and Lady Attenborough, and a good selection of painting and sculpture by some of our best-known UK artists from the 1700s to the present.

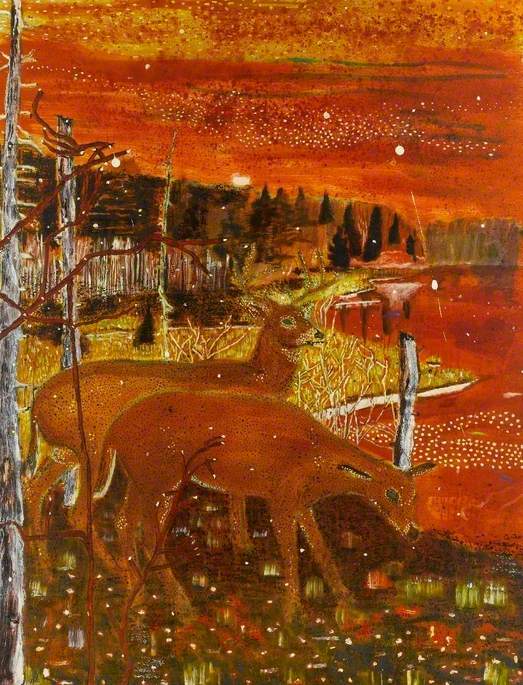

Hogarth’s conversation piece is one of these and takes pride of place in the museum’s newly-refurbished main permanent gallery. It is a stunning picture. The artist was already becoming popular, but only at the start of his career when he painted the Wollaston family in 1730, and it is one of his most ambitious early works. Whereas his conversation pieces from this period are generally just over twelve inches high, this is much bigger. It includes 17 individual images of men and women, including servants at work and family members, who are shown in a sumptuous interior, in conversation, playing cards and taking tea. The head of the household, William Wollaston, stands centre stage. He acknowledges his family with a sweeping gesture, whilst turning reverentially towards a marble bust of a man on the chimney-piece.

William Wollaston and his Family in a Grand Interior

1730

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

In a typical Hogarthian touch, in the foreground, a mischievous little pug looks straight at the viewer, standing on its hind legs with its front paws upon a chair, as if making a subtle comment on this family’s aspirations. The model was quite possibly the painter’s own pet. Hogarth owned at least three pugs in his lifetime, creating a canine association he apparently enjoyed. A few years later he began his well-known

Most of Hogarth’s paintings on public view in the UK, like this

Assembly at Wanstead House

1728–1731, oil on canvas by William Hogarth (1697–1764). The John Howard McFadden Collection, 1928

In both pictures, a classical-style marble bust looks down on the assembled company from a chimney-piece to the right. In the Wanstead House picture, the subject is probably Julia, Pompey’s wife. She appropriately represented the theme of marital fidelity, since the painting may have celebrated the 25th wedding anniversary of Lord and Lady Castlemaine. In contrast, the bust in the Leicester picture is thought to show William’s unmarried older brother Charlton Wollaston (1690–1729). With his death, just the year before the picture was created, William Wollaston, a ‘second son,’ inherited the family fortune. The black draperies in the room and the garments worn by some sitters also suggest a period of mourning is underway.

While directly a homage to William’s deceased older brother, the source of his newfound wealth, this picture might also be intended indirectly to raise awareness of their father William Wollaston Senior, who died in 1724. He was indeed an important figure, and one well worth drawing attention to by his aspirational son. He was a teacher, a Church of England priest, a scholar of Latin, Greek and Hebrew, a theologian, and a major philosopher. He was famous for one book, completed just before his death, called The Religion of Nature Delineated. It was hugely popular, selling 10,000 copies through many editions. Such was his fame that in 1732 Queen Caroline placed a marble bust of Wollaston, along with those of Newton and Locke, in her hermitage at Richmond. In our own times, with regard to eighteenth-century philosophy and natural religion, he is still ranked alongside the best-known Enlightenment philosophers. William Senior had inherited the bulk of the family estates, which included the manor of Shenton, near Market Bosworth in Leicestershire (hence the longstanding Leicestershire connection). He married Catharine Charlton, daughter and coheir of a London merchant. They lived in Charterhouse Square until their deaths in the 1720s.

William Wollaston, Junior married Elizabeth Fauquier. Her father was governor of the Bank of England, and together they had eight children. They lived on another of the family estates, at Finborough Hall in Suffolk, and soon after the picture was completed its commissioner became MP for Ipswich and remained so until 1741. His eldest son, another William (1731–1797), was also MP for Ipswich and commissioned Thomas Gainsborough to paint two portraits of him. One of the

I hope you will consider helping to keep this wonderful artwork in Leicester. To make a donation, please visit www.leicester.gov.uk/hogarth

Sarah Levitt, Former Head of Arts and Museums, Leicester City Council

For further details on how you can help, please contact Philip Hackett, Resources Manager, Leicester Museums on philip.hackett@leicester.gov.uk or 0116 454 3111

Update: In May 2019, following the campaign, the painting was allocated to the New Walk Museum & Art Gallery via the Acceptance in Lieu scheme.