Since launching the Art UK sculpture project we have digitised thousands of sculptures made from a myriad of different materials.

It may come as no surprise that one of the most prevalent materials in the history of sculpture is stone – a versatile set of naturally occurring minerals that artists have carved since prehistoric times. The durability of stone has allowed sculptural and architectural fragments to endure throughout history.

Ancient carving

Even before stone was used as a sculptural material, it was used as an artist's tool. The earliest works of art made by humans include ancient cave paintings, some carved with flint.

The earliest stone sculpture known to humankind is the Venus of Hohle Fels, which was discovered in southwestern Germany in 2008 and was made between 33,000 and 38,000 years ago.

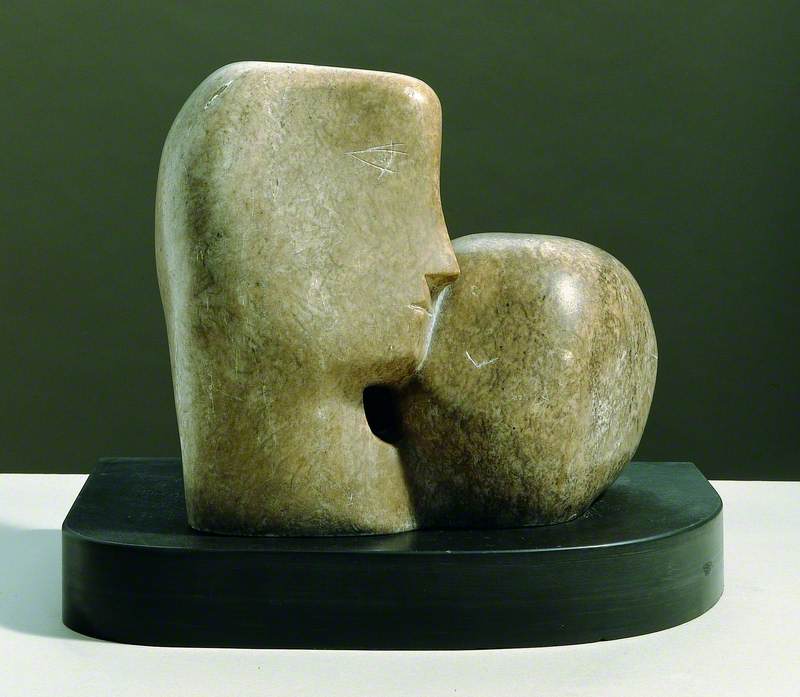

Ain Sakhri lovers figurine

c. 10,000 BC (the Natufian period), calcite cobble, found at Wadi Khareitoun, Judea, near Bethlehem

The Ain Sakhri lovers figurine in the British Museum is the oldest known sculpture of human beings making love and is at least 10,000 to 11,000 years old.

The natural shape of calcite cobble was moulded to represent the outline of entwined lovers. It is named after the place where it was found, in the cave of Ain Sakhri in the Wadi Khareitoun, outside of Bethlehem.

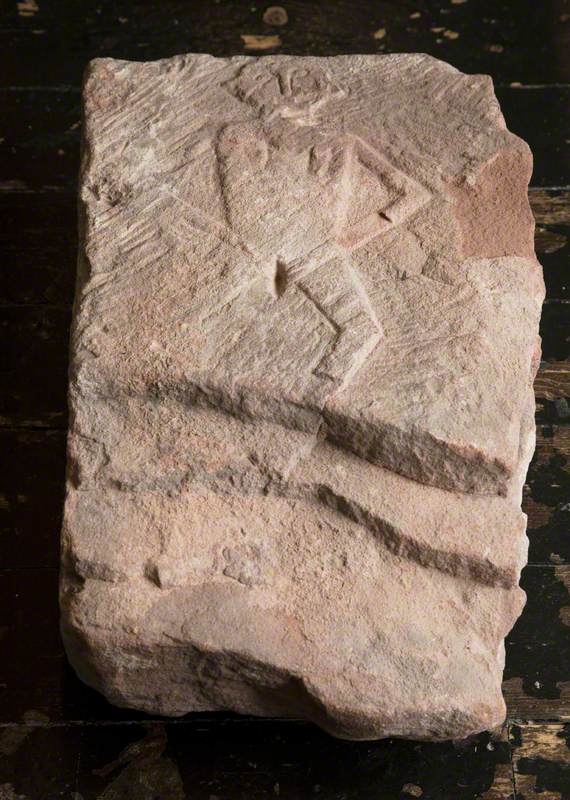

Another example of early carved stone sculptures in the UK are sheela-na-gigs, figurative carvings of unclothed women displaying their genitals to ward away bad omens and evil spirits. This kind of 'architectural grotesque' can be found all over Britain, in the corners and crevices of churches, cathedrals and castles.

To find out more about these wonderful carvings, explore The Sheela Na Gig Project.

In Romanesque and medieval architecture, stone 'corbels' (decorative fragments and structural supports) were carved to resemble grotesque figures – monstrous faces and gargoyles. Like sheela-na-gigs, gargoyles had a direct function – to drive evil spirits out of the church. Typically they resembled clawed ravens, dogs or hybrid creatures that could instil fear in the eye of the beholder.

Marble mania

By the time the Renaissance had flourished across Europe, marble was the most sought-after stone. Although rare and expensive, it was used widely in both architecture and sculpture.

Marble was prized for its translucency, durability and naturalistic physical properties.

Renaissance Italian artists favoured marble for its allusion to the classical world – Hellenistic Greece and the Roman Empire.

Popular marbles included Pentelic, Parian and Carrara, which were transported across Europe to Britain. Before marble mania spread from Italy to Northern Europe and Britain, artists often used indigenous British metamorphic rocks: limestone and sandstone.

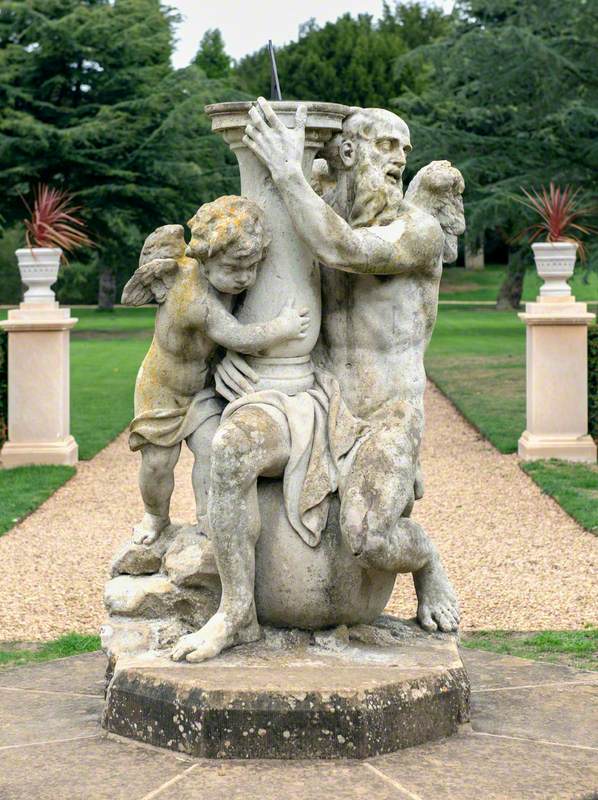

Father Time with Putto

1688–1724

Caius Gabriel Cibber (1630–1700) (attributed to)

Particularly in the eighteenth-century Neoclassical period, sculptors continued to imitate the marble busts from antiquity, with many members of the British nobility and elite presenting themselves in white stone.

Portland limestone was another type of stone regularly used by artists working in Britain, as seen in this sculpture Father Time with Putto found at Belton House. This typically English rock is quarried from the Isle of Portland, off the coast of Dorset.

A grey-white stone, Portland limestone is the stone found most ubiquitously across London. Architectural landmarks such as Buckingham Palace, St Paul's Cathedral and the British Museum were constructed with this stone.

The use of stone in architecture also allowed for decorative carvings on the facades and friezes of buildings. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, public stone sculptures became increasingly prevalent as war memorials were commissioned, particularly following the First World War.

Modern sculpture

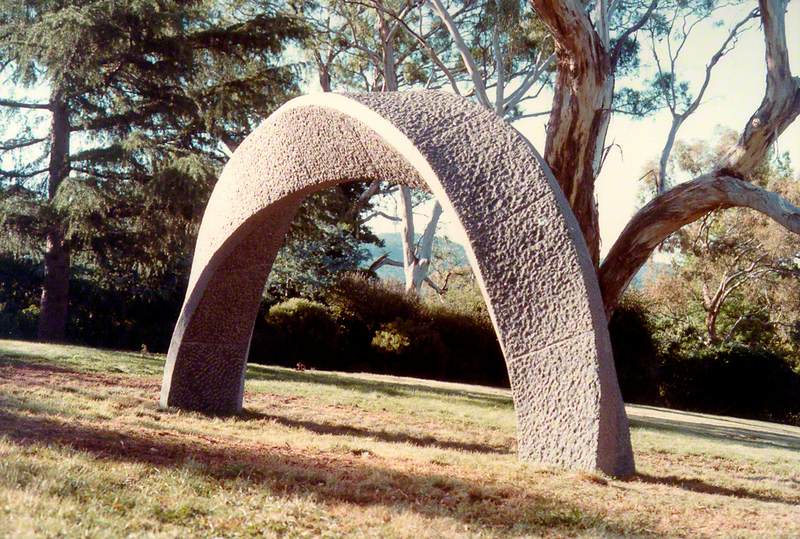

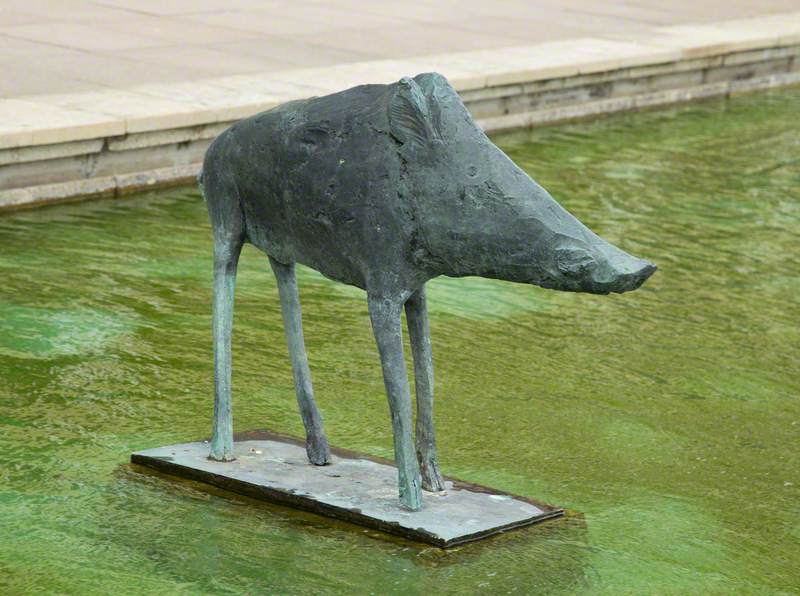

One of Britain's most famous sculptors, Henry Moore (1898–1986), often carved in stone.

Although many of his most famous outdoor sculptures were cast in bronze, Moore once described himself as 'naturally... more a carver... than a modeller.' It is estimated that over the course of his career, he used over 41 different types of stone.

Another titan of British modernism, Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), also carved in stone. Hepworth was friends with Moore, and both sculptors were working in the aftermath of early twentieth-century modernism, when sculptors like Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and critics such as Roger Fry advocated for a 'truth to materials'.

The Barbara Hepworth Sculpture Garden in St Ives, Cornwall is full of her bronze, wood and stone works. Also on display are her sculpting tools: chisels, saws and hammers.

Stone is still used widely today by contemporary artists. In this video made for Art UK by Culture Street, sculptor Dawn Rowland demonstrates how she carves from blocks of stone to produce her figurative sculptures.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Sebastiano Barassi and James Copper, 'Henry Moore and Stone: Methods and Materials', in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015

.jpg)