Over the last few weeks, we have become extremely familiar with the inside of our homes. Many of us are probably getting bored with seeing the same rooms, the same décor, the same clutter day in, day out. We have also realised that the things we have in our homes say a lot about us and the lives we lead.

It's not only our own homes that we are seeing afresh. With lockdown plunging us into a world where work and social lives are played over video calls, we have been able to sneak into the homes of friends, colleagues and even celebrities, in the name of connectivity. The domestic interiors of public figures have been scrutinised during remote TV appearances, their bookshelves and artworks seized upon as a glimpse into their unfiltered souls. Such intimate access to the homes of society's rich and powerful would have been tabloid gold-dust in a pre-lockdown world.

This snapshot into the lives of others is not entirely new, however – artists across the centuries have taken inspiration from their immediate surroundings, depicting themselves and their lives through the places they inhabit. To satisfy your curiosity for the private lives of others, here are five artists with paintings in the Royal Academy's collection that give a glimpse into their homes or home studios.

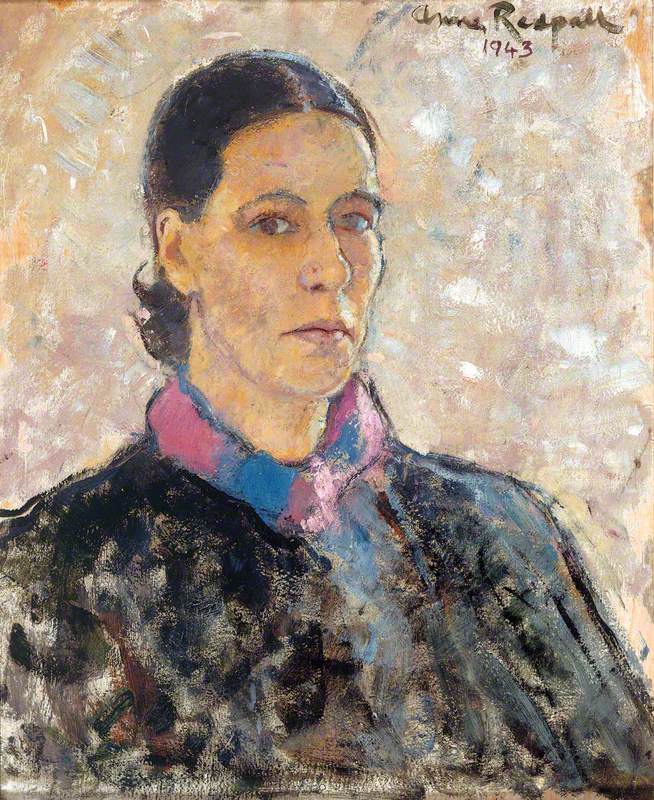

Jean Cooke

Jean Cooke (1927–2008) was a leading female painter of the twentieth century. This painting captures a snapshot of everyday life with her husband, the artist John Randall Bratby (1928–1992), in their top-floor flat in London. Bratby's relaxed pose, the commonplace items strewn across the table and the open doors in the background – hinting at a life beyond the canvas – imbue the painting with a sense of spontaneity. We imagine Cooke has just finished breakfast, taking the opportunity to record an unremarkable moment, drawing back her chair from the table to paint the scene before her.

Cooke found endless sources of inspiration in her domestic environment, revealing much about her everyday life. The simple spread of fruit, bread and butter and tea reflects the humble existence of the couple – who at the time were students at the Royal College of Art in London. But this was not just student life: this was an era of post-war austerity. The scene depicted here was the reality for many in 1950s Britain. With money scarce, Cooke had even more reason to turn to whatever she saw around her home as subject matter for her works.

The open door behind Bratby shows a canvas daubed with white and green. With two young artists living in a small flat, it is unsurprising that artworks coexist with their makers. Space is limited, as suggested by the closeness of the walls and the canvas cutting off the top of Bratby's head and front corner of the tablecloth. As many of us are discovering, when people live and work in close proximity, we have to get inventive with the use of space. Here, the back room is a makeshift studio, and the corridor doubles as a dining room.

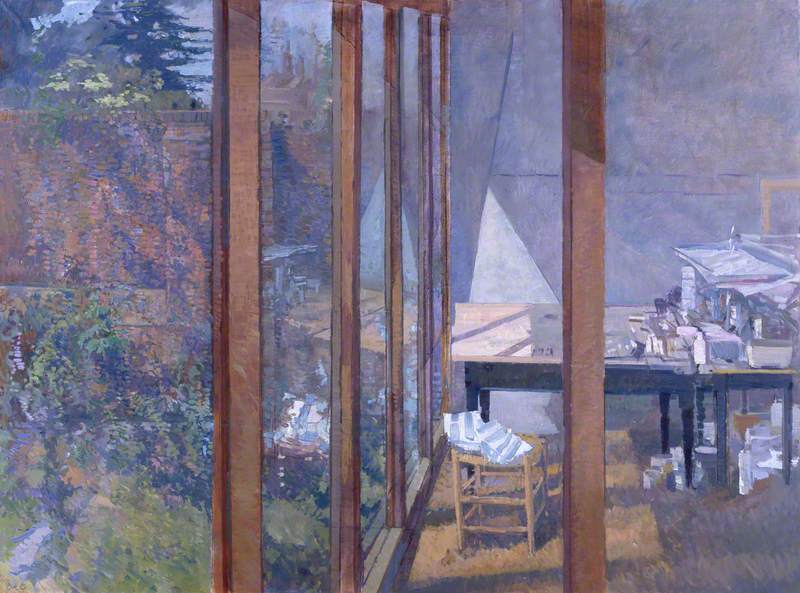

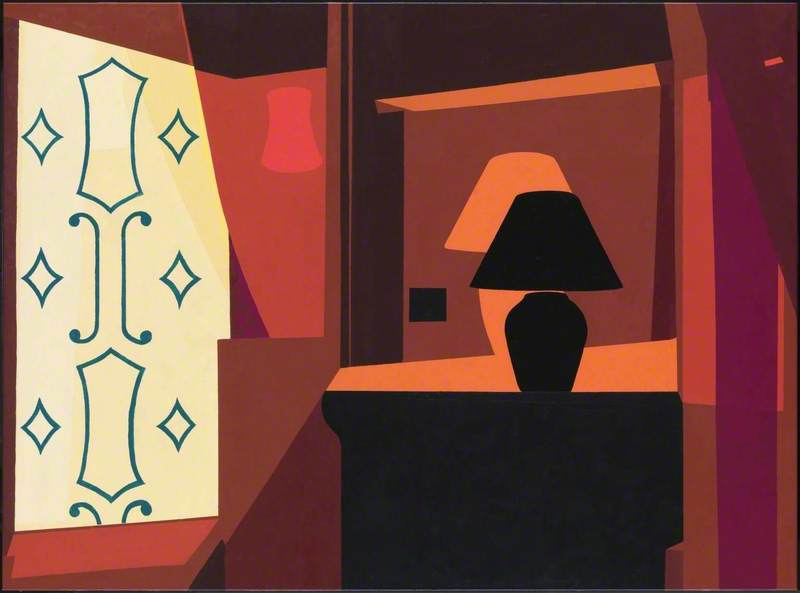

Roger de Grey

Roger de Grey (1918–1995), best known as a landscape artist, also created many paintings of his home. Interior/Exterior (1992) shows the artist's studio overlooking a lush garden, a large window acting as an ambiguous frontier between inside and outside space. De Grey presents the two sides of the work as a continuous scene, offering the view as a landscape of the artist's life. He treats each aspect of the canvas with equal care, with the objects on the table and the foliage in the garden all painted with similar attention.

The glimpse into Roger de Grey's home studio is a subtle reflection of his artistic life: unostentatious, the muted tones of paint pots and artistic equipment almost camouflaged against the background. The simple decoration of the studio contrasts with the frenzy of colourful brushstrokes outside. This presents his studio as a place of calm reflection for the artist, while his garden – and the outdoor world more widely – reveals a place of dazzling inspiration and energy. On the left, he depicts raw inspiration and passion; on the right, quiet contemplation and precision.

Organised and meticulous, Roger de Grey served as Treasurer and then President of the Royal Academy across three decades. Under his leadership, the Academy flourished, and he was influential in the development of the vibrant exhibition programme. De Gray's attention to detail is reflected in the way he paints and in the tidy appearance of his studio – a contrast to many artists' studios.

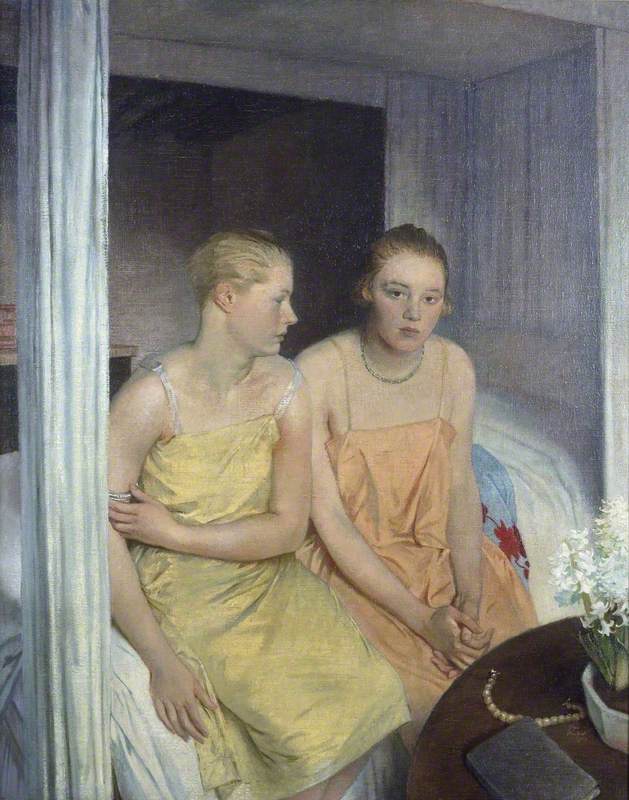

John Stanton Ward

At the other end of the spectrum, in the studio of John Stanton Ward, we find eclectic objects piled on the table and peppering the floor, and three of the artist's young children jostling for attention. Ward was obviously making a portrait of one of the girls – perhaps her curious siblings couldn't resist seeing what was going on. Today, any parent working from home can empathise with such invasions of children in our makeshift offices.

The careful positioning of his sitters and objects reveals a thoughtful composition that belies the apparent chaos of the room. Ward has carefully formed this interior to act as a cross-section of his life: chaotic yet attractive, the image of the inspired artist at work. The miscellany of objects in Ward's studio indicates his propensity for antique and decorative objects. China figurines, musical instruments and a painted screen reflect Ward's wide-ranging interests and love of travel. In this view of his studio, Ward shows us how he desires to be perceived – as a family man, an important portraitist and a collector of curiosities. Ward was a successful portraitist, undertaking commissions for eminent public figures and royalty including the Queen and Princess Anne.

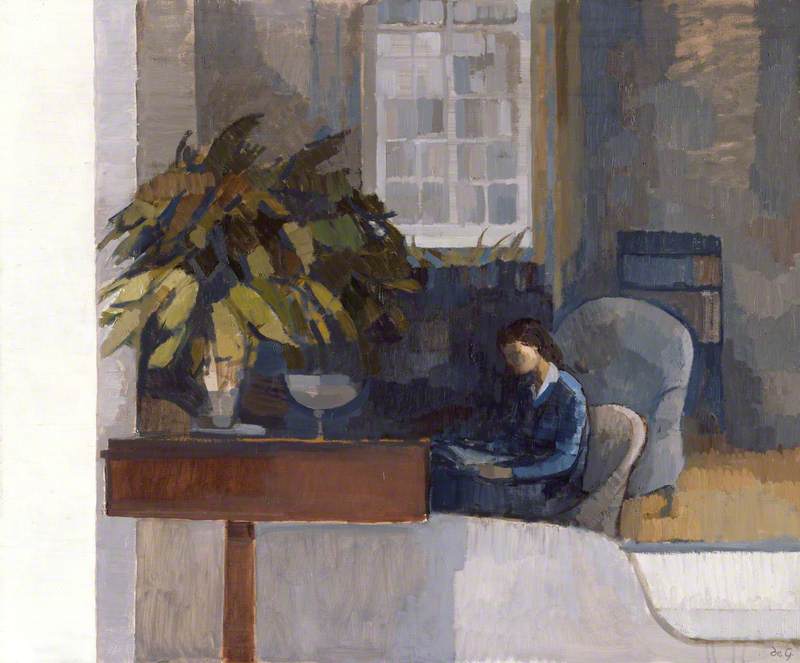

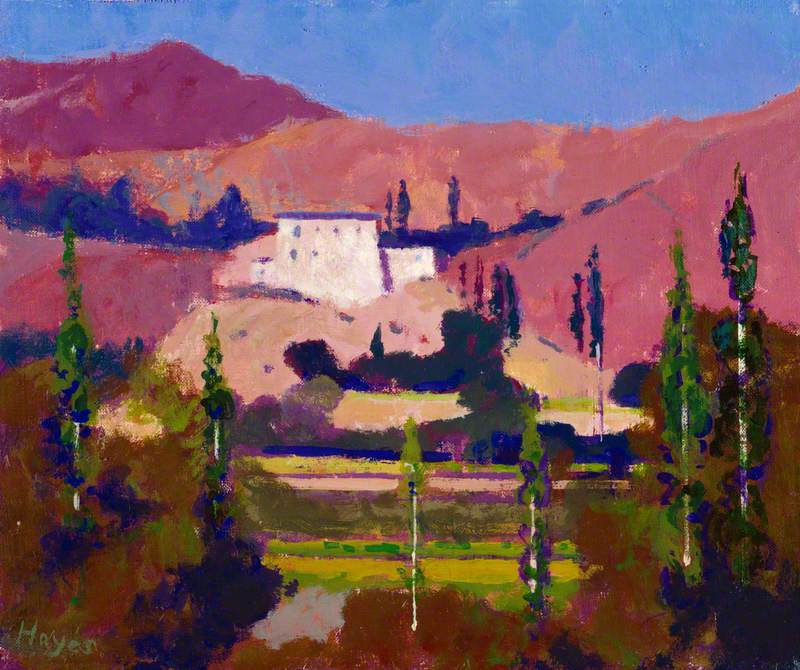

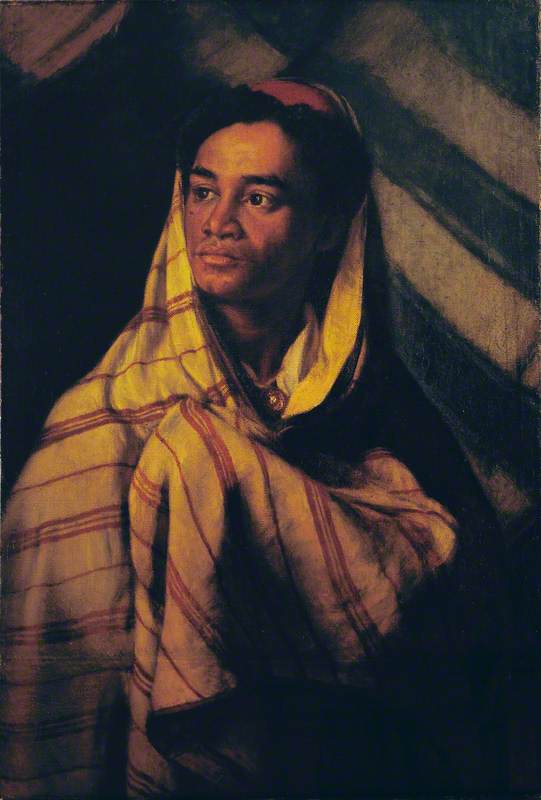

Colin Hayes

In the atmospheric depiction of Interior: Girl Seated at a Table, Colin Hayes (1919–2003) presents us with a quiet moment: his daughter glimpsed reading at the kitchen table. She is unselfconscious, unaware of being the subject of the painting, completely absorbed by her book. This painting is as much about the mood of the moment as the room's physical appearance. Hayes believed artworks should convey an idea – if a painting merely captured the physical appearance of a scene, the artist would dismiss it as mere illustration.

Interior: Girl Seated at a Table

c.1961

Colin Graham Frederick Hayes (1919–2003)

In the kitchen interior, the contrast between the brightness of the table and the dark clothing of his daughter demonstrates his attention to how light falls across a room. The individual brushstrokes and flat patches of colour imbue the painting with an abstract quality. By reducing detail, the artist emphasises the aura of the work, suppressing specifics in favour of evoking an overall effect – a still and reflective atmosphere. The simple interior and tranquillity of the scene reflect Hayes' gentle nature.

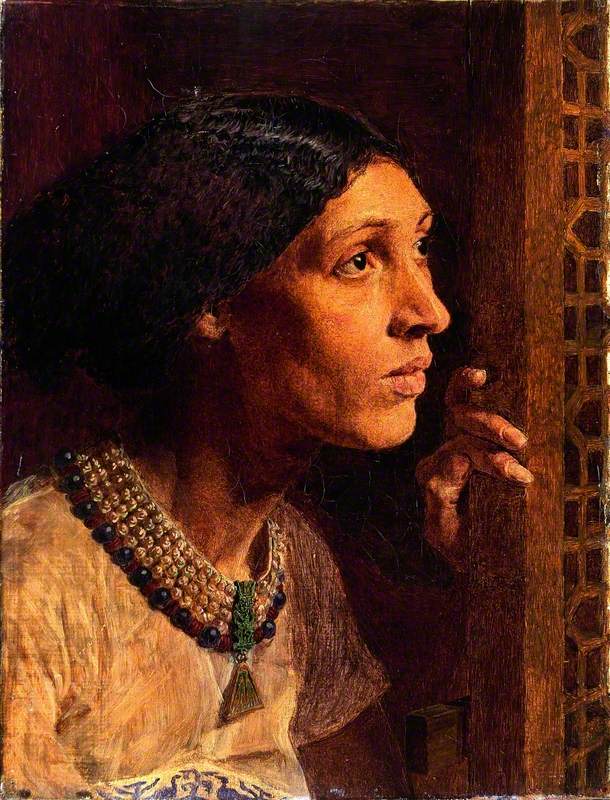

Hayes was mainly known as a landscape painter, much inspired by his travels to North Africa during the Second World War and later by painting trips to Greece, Tibet and India. The vivid colours and effect of light in these distant lands informed his painting throughout his life.

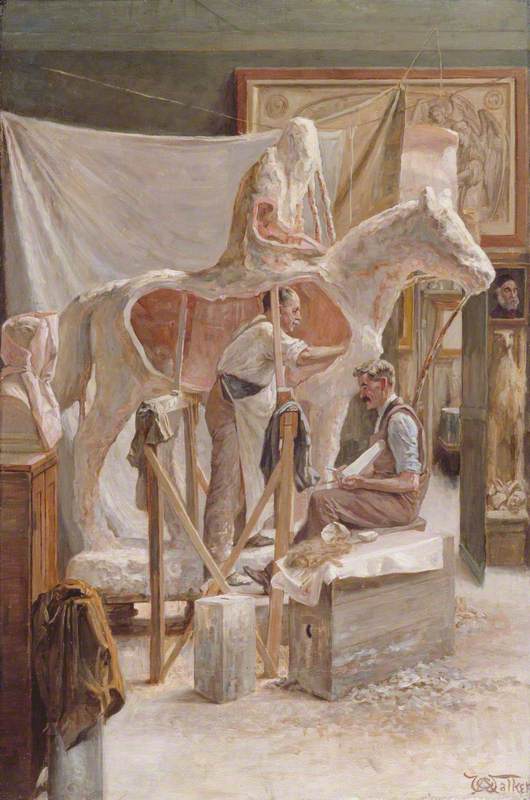

Arthur George Walker

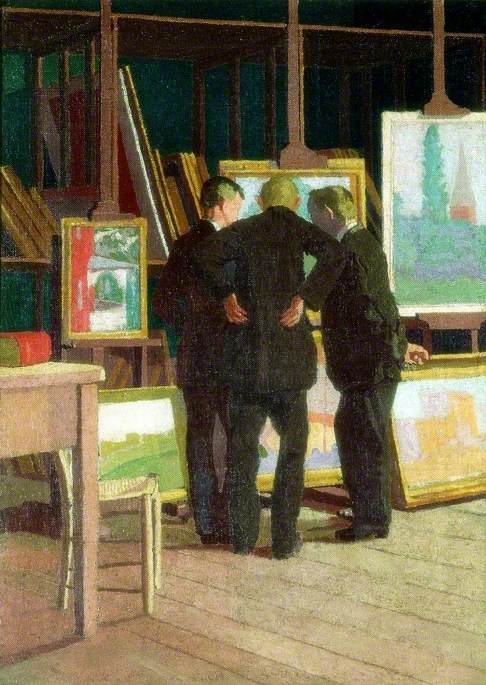

Arthur George Walker (1861–1939) was an artist bordering on the obsessive. This interior view of his Chelsea home-studio acts as a portrait of the man and his character. Predominantly a sculptor, Walker was also an accomplished painter.

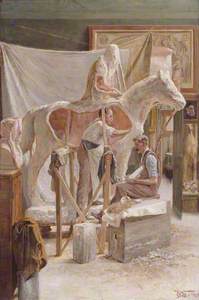

The space depicted in this painting is immaculate and well-ordered: it seems more like a gallery than a workshop. Displayed around the room are countless of Walker's sculptures, including The Necromancer (c.1926) on the left-hand shelf, a back view of Grief (1915) to the right and the equestrian statue of John Wesley (installed in Bristol in the 1930s) at the rear.

The number of works appearing in this painting attest to the sheer volume of Walker's output; for him, art was everything. Perhaps this is why the figures at the table, with the artist’s brother Harold on the right, appear somewhat frustrated that Walker cannot spare a moment to have tea with his family. Harold looks on with resigned impatience and his female companion makes it clear that posing for the painting is an unwelcome interruption in her teatime conversation.

The lack of clutter and mess is surprising for a studio. Sculpting, particularly carving marble and plastering, creates all sorts of detritus. Yet here we are presented with a spotless interior. This is a conscious decision by the artist; either he made a special effort to clear the space before welcoming his guests, or he subtly excluded whatever mess there was from his painting.

By comparison, The Artist's Studio – made around the same time – reveals that Walker's studio was a truly multipurpose space. Here, two assistants are seen in the very space that Walker's brother and friend occupy in Tea in the Studio. Gone is the tidy table and tea-set; in their place a work-in-progress plaster statue.

Admittedly, we have always been a little nosey when it comes to other people's homes. This curiosity is nothing new – it's just that now, endless video calls have given us novel access behind closed doors.

Artists have represented their own homes for many reasons: whether as an incidental background, to capture a certain mood, or as a form of self-examination. Perhaps now is the time to take inspiration from this and make sure our homes give the desired impression to our Zoom contacts – and to the world more widely.

Helen Record, Curatorial Assistant at the Royal Academy of Arts