'Someone will remember us...' – Sappho (c.630–c.570 BC)

In 2017, I decided I wanted to read an anthology of poems by women that would cover many centuries and showcase different voices and points of view – but I found nothing that fitted the bill. The seed for She is Fierce: Brave, Bold and Beautiful Poems by Women was planted, and I have loved researching female poets – some well known, and many all but forgotten – from previous centuries as well as including some of today’s brightest young talents. The art in UK public collections includes fascinating paintings of some of these writers, and finding their portraits while researching their biographies for the book has been an enormous pleasure.

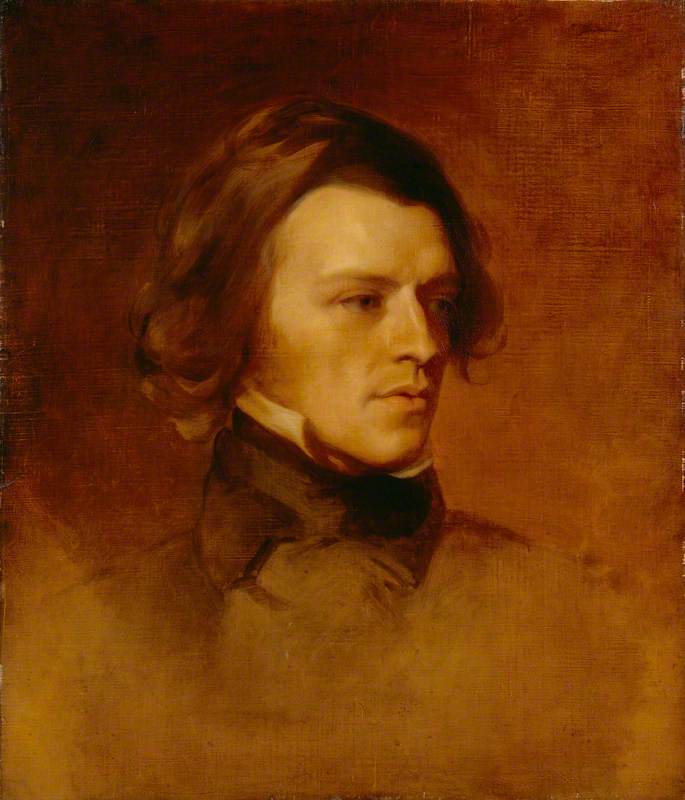

1. Joanna Baillie (1762–1851)

Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), Poet

John James Masquerier (1778–1855)

An outdoorsy girl who couldn’t read until she was 11, Joanna had a small inheritance that enabled her to pursue a writing career. She also wrote plays, though felt they were dismissed as ‘closet drama’ – to be read rather than performed – because she was a woman. Joanna’s poetry was popular, and she used her influence to support women and working-class writers. She donated half the proceeds of her books to charity. One critic, Francis Jeffrey, was rude about her plays, and she refused to meet him for many years but – typically – once she finally made his acquaintance they became great friends.

2. Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

Elizabeth received an excellent education at home from her adoring but overprotective father, and published poetry from her teens onwards. Despite living as an invalid and recluse, her poetry was hugely popular. She attracted fan mail from Robert Browning – then an aspiring poet, six years her junior – and their relationship revived her sufficiently to elope with him to Italy, get married and have a son. Her father never forgave them. A greater celebrity than her husband during their lifetimes, Elizabeth also involved herself in contemporary politics. She was a passionate critic of slavery and child

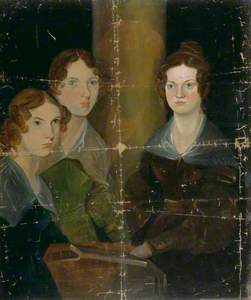

3. The Bronte Sisters: Anne (1820–1849), Charlotte (1816–1855) and Emily (1818–1848)

The Brontë Sisters (Anne Brontë; Emily Brontë; Charlotte Brontë)

c.1834

Patrick Branwell Brontë (1817–1848)

Anne’s novel Agnes Grey was about a petted and

After a sheltered childhood on the Yorkshire moors, Charlotte

Many of Emily’s poems originated in her

4. George Eliot (1819–1880)

Mary Ann Evans, 'George Eliot' (1819–1880)

1880/1881

François d' Albert-Durade (1804–1886)

Mary Ann Evans published under a male pseudonym because she wanted her novels – which include Middlemarch – to be taken seriously, but also because of her personal life. She lived with George Henry Lewes, who was married (though his wife had children with another man). Although affairs were not uncommon, their openness was. It was the cause of a decades-long rift with her brother Isaac – to whom her 'Brother and Sister' sonnets are addressed, some 20 years after they were estranged.

5. Winifred Holtby (1898–1935)

Winifred Holtby, Undergraduate (1917–1921)

1936

Frederick Howard Lewis (1885–1969)

I love this lively portrait of a fiercely intelligent young woman, who makes confident eye contact with the viewer. A feminist, socialist, pacifist and campaigner against racism, Winifred once wrote that a ‘passion for imparting information to females appears to be one of the major male characteristics’, spotting instances of ‘mansplaining’ 70 years before the word was coined. In 1931 she was diagnosed with Bright’s disease and given two years to live, and she poured all the energy of her last months into writing South Riding. Although better known during her life for her journalism, it is this last novel for which she is now remembered.

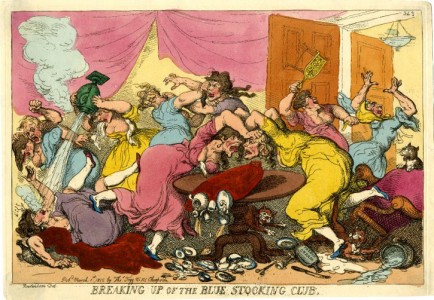

6. Hannah More (1745–1833)

There are several paintings of Hannah on Art UK, but this one is the liveliest. Hannah campaigned against slavery and was a member of the Bluestockings, an eighteenth-century women’s society who gathered to discuss intellectual matters. She established schools for the poor in the west of England.

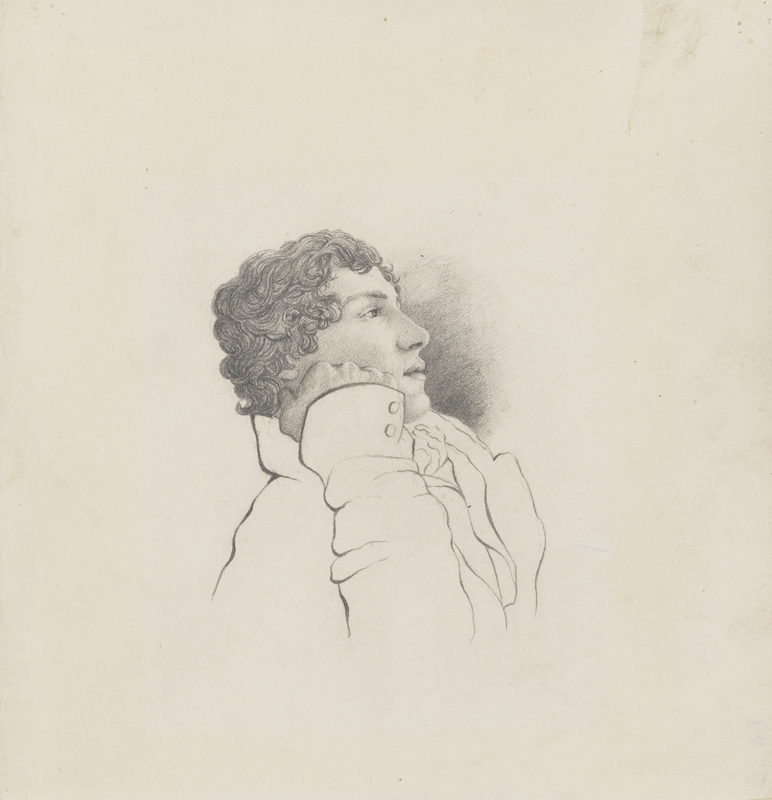

7. Christina Rossetti (1830–1894)

In contrast to her brother, the wild-living Pre-Raphaelite artist

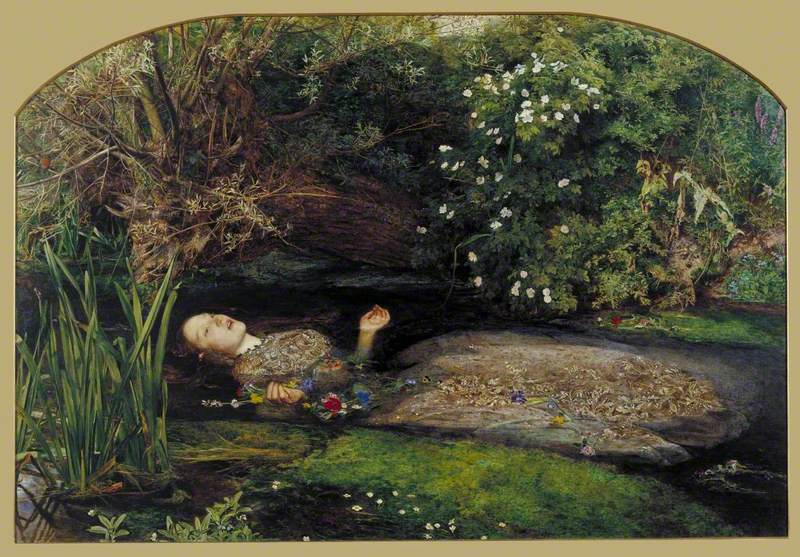

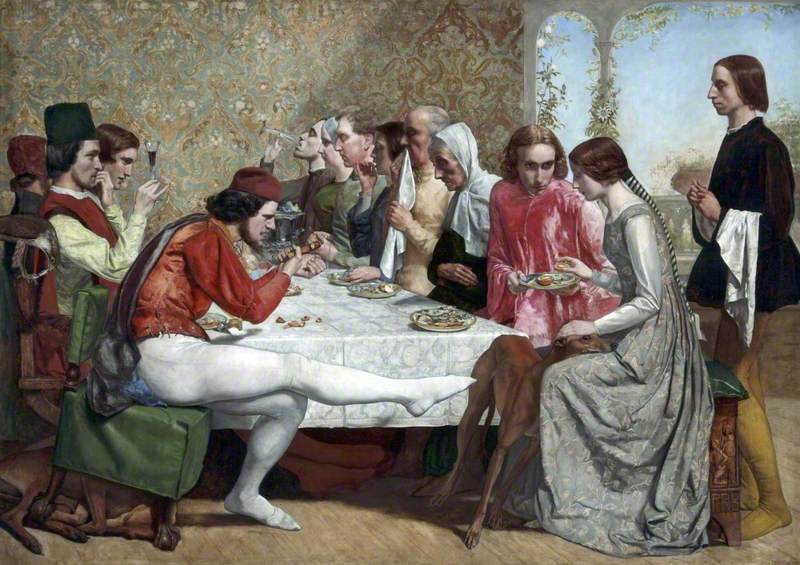

8. Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862)

Elizabeth was working in a hat shop when one of the Pre-Raphaelite painters persuaded her to model for him. Millais painted her as Hamlet’s Ophelia in this iconic painting, though she became ill because she remained still and uncomplaining when the lamps warming the bath in which she was posing blew out. Painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti fell in love with her and painted her obsessively. Scandalously, they lived together for eight years before marriage – Rossetti was reluctant to introduce the working-class Lizzie to his aristocratic family, and she constantly feared (with good reason) that younger models would claim his heart. She suffered from depression, poor health

9. Vita Sackville-West (1892–1962)

This is a soulful and beautiful portrait of the young Vita, playing dress up in Ellen Terry’s finery. Vita and her husband Harold Nicholson had an unconventional relationship with both having affairs with men and women. Vita’s lovers included Virginia Woolf, who was inspired by her to write Orlando. It was a difficult time to have same-sex relationships and Vita struggled with her feelings and the lack of social tolerance.

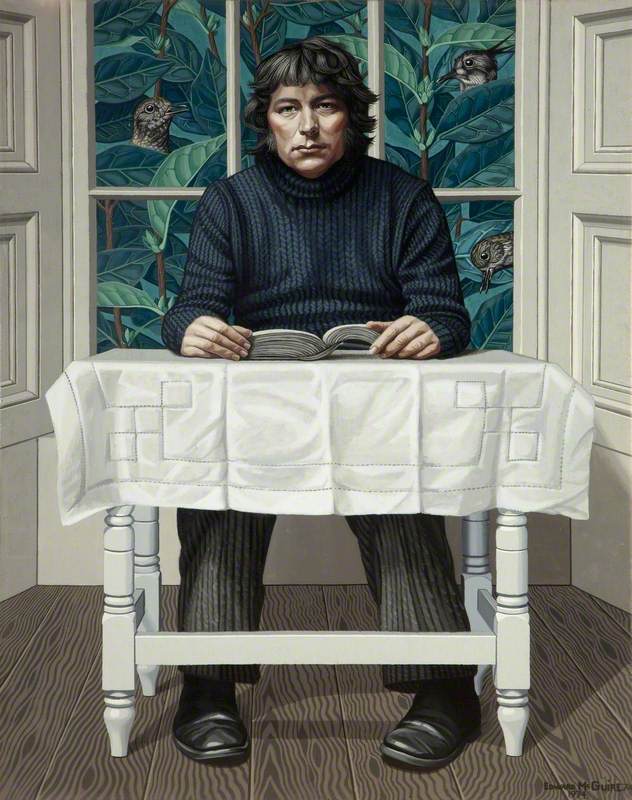

10. Sappho (c.630–c.570 BC)

Most of Sappho’s poems survive only as fragments. We do know that she was praised throughout the ancient world – Plato called her ‘the tenth Muse’. At a time when most poetry was formal and meant for public performance, Sappho wrote daringly and passionately about her private feelings including love poems addressed to women. She has been imagined in many guises by artists – mostly male artists – throughout the centuries, but this clear-eyed, serenely impish portrait is my favourite.

Ana Sampson, author of She is Fierce: Brave, Bold and Beautiful Poems by Women, published by PanMacmillan