On the cusp of noon, 21st October 1805, the famous flag signal 'England expects that every man will do his duty' was hoisted by Admiral Nelson to commence the highly anticipated battle.

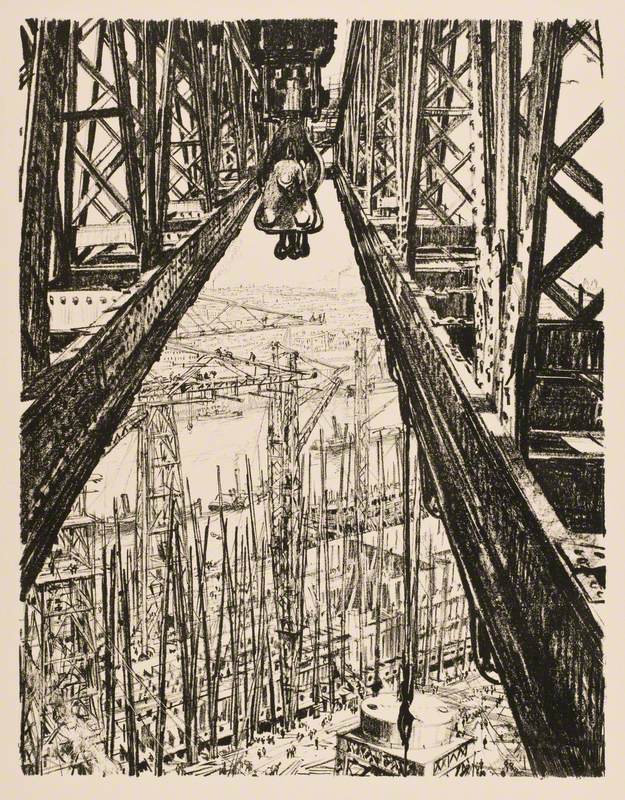

Taking place in Cape Trafalgar, just off Cadiz in south-west Spain, Napoleon's wish for France to establish naval superiority over Britain was to be tested. The two-column formation of the British fleet began sailing east, nearing a 90-degree angle to intercept the curved line of the Franco-Spanish fleet – currently facing north. An absence of wind left the fleet of 27 ships cruising incredibly slowly, perpetual stillness engulfing the air.

The flagships Victory and Royal Sovereign lead their columns towards either end of the Franco-Spanish fleet; Nelson's Victory was heading towards the Spanish Vice-Admiral Villeneuve's Bucentaure, whilst Commander Collingwood's Royal Sovereign sailed towards Spanish Commander Gravina's Santa Anna.

Britain's two columns were nearing east, with Royal Sovereign taking lead to be the first ship to cut through the southernmost line of the combined fleet.

It was then that Villeneuve sent the signal 'engage the enemy', allowing the French ship Fougueux to fire the first shots at Royal Sovereign. The easternmost column was under heavy fire and was naked in their defence, for they could not fire until breaching the enemy line. With the Royal Sovereign finally piercing the southernmost line of the Franco-Spanish fleet, the following 13 British ships began joining in one by one.

The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

Nicholas Pocock (1740–1821)

Nelson's flagship Victory shortly followed by successfully intercepting the northernmost line, breaking between Bucentaure and French ship Redoubtable. Three British ships gradually entered the firing line and Redoubtable was left locking horns with Victory.

With endless bombardment, Nelson and captain Thomas Hardy continued directing their crew amidst the chaos and the cannons – until a French bullet struck down Nelson.

The Fall of Nelson, Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

c.1825

Denis Dighton (1792–1827)

Impaling his left shoulder, passing through his spine to finally being lodged below his right shoulder blade, the marksman's shot proved fatal.

The Death of Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

c.1806

Samuel Drummond (1765–1844)

Nelson was rapidly carried under deck for medical attention and to avoid demoralising the crew, but the Vice-Admiral already accepted his fate, telling his surgeon, 'You can do nothing for me. I have but a short time to live. My back is shot through.'

Though the British were losing Nelson below deck, they were winning above deck in the battle. Bucentaure was the first ship to surrender and the numbers grew by the minute due to more and more British ships entering the battle. The British fleet slowly overwhelmed the battleground and Nelson's tactic was proving successful; the British ships in the back of their column had perfect positioning to hurdle even more damage to the already war-torn enemy ships.

The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805

Thomas Luny (1759–1837)

Below Victory in the cockpit, rushed palliative care was in force to make Nelson comfortable in his last hours.

Wine and lemonade was served to him with an entourage of mourners surrounding his tired body. As he remembered his family and friends, Nelson's voice slowly dissolved, his pulse weakening by the minute. At around half-past two, Nelson was informed of the several surrendered enemy ships, and a feeling of relief engulfed his body. Uttering the words 'God and my country', Nelson slowly began to slip away. He died at half past four.

The Death of Lord Nelson in the Cockpit of the Ship 'Victory'

1808

Benjamin West (1738–1820)

The battle ended shortly after, with Britain successful.

The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805: Position of the Fleets at 4.30pm

after 1837

William John Huggins (1781–1845)

Public celebration for the victory was overshadowed by nationwide mourning for Nelson's death.

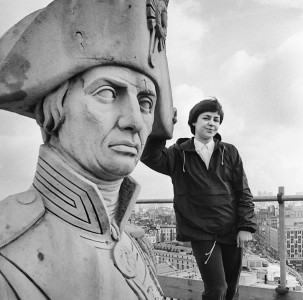

The famous Nelson's Column in London's Trafalgar Square was just one of the many monuments erected to honour his legacy.

His strategic thinking and critical assessment before and during battles solidified his status as the ultimate naval commander. Partnering this with his supreme confidence, he helped Britain remain navally superior following their 22-year struggle with the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

The battle itself also secured Britain's naval dominance across the world, acting as a deterrent for Napoleon's revived plan of invading Britain. The daring tactics used in the battle, alongside the perseverance of the British fleet solidified the nation's control of the seas.

Avesta-Saule Zardasht, student on the Art History A level and EPQ course run by Art History Link-Up