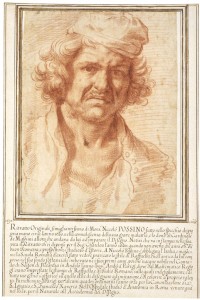

Sometimes however careful one is there are occasions when art history grows a hydra’s head and sends the writer into a quagmire from which there is little escape.

Fantastic Ruins with Saint Augustine and the Child

1623

François de Nomé (c.1593–after 1644)

‘Desiderio Monsù’ was a mid-twentieth-century name for a widely scattered group of pictures, many of them morbidly fascinating.

The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine

François de Nomé (c.1593–after 1644) and Didier Barra (c.1590–after 1652)

Then came the breakthrough: there were two painters, François de Nomé and Didier Barra. They both came from Metz, which at that time was an independent bishopric in eastern France. It was in this province that Georges de La Tour had been born in Vic-Sur-Seille, and only in 1620 that he moved to Lunéville in the Duchy of Lorraine.

It appears that both artists worked in Naples and it was there in the Spanish-ruled city that they created their fantastic visions. French writers had a lovely time with purple prose: ‘The Black of Cassandra’, ‘Rivers of Lava’, ‘Subterranean Earthquakes’ and so on.

Certainly there is nothing prosaic about either artist, but most of the really dramatic scenes are given to François de Nomé.

Since the early 1960s The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has had a wonderful picture. It used to be called An Explosion in a Church, somewhat improbable for seventeenth-century Naples. Then it was correctly identified as King Asa of Judah Destroying the Idols. The fact that he appears to be doing it with gunpowder may have been the cause of the mistaken identification.

In spite of these artists’ talents, one looks for them in vain in mainstream art history. They still stand, waiting, like Georges de La Tour had to wait, not for an apologist but for someone who has the foresight to integrate them into the context of seventeenth-century European painting.

Christopher Wright, Art UK advisor, art historian, artist and author of numerous catalogues of Old Master paintings in Britain