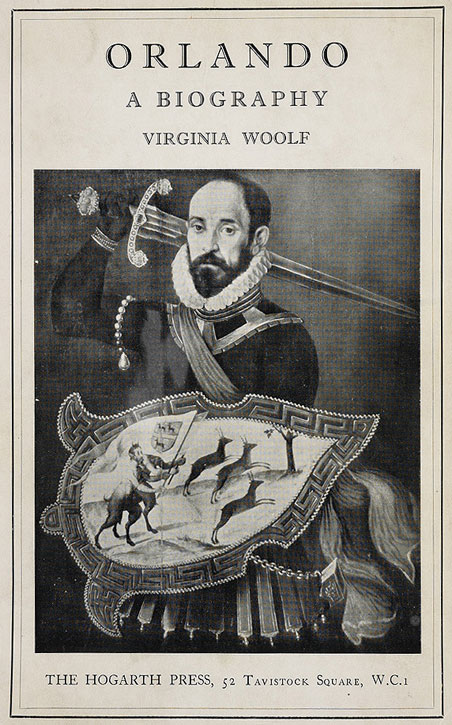

Virginia Woolf's 1928 novel Orlando is a masterpiece of modernist queer fiction. Chronicling the life of the titular protagonist, who changes sex from male to female and lives for over 400 years, the novel is both a satire of English historiography and a love letter to Woolf's partner, friend and muse, Vita Sackville-West.

Cover of the original copy of Virginia Woolf's 'Orlando: A Biography'

In 1992, the story was further mythologised in the film Orlando, directed by Sally Potter and starring Tilda Swinton.

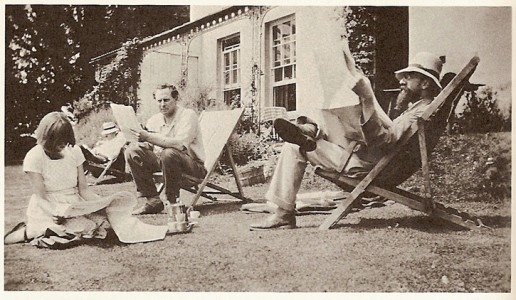

Sackville-West was a writer, gardener, and fellow member of the London group of writers and artists known as the Bloomsbury Set. She and Woolf were lovers for over ten years. It was this relationship which inspired Orlando, a novel which Sackville-West's son, Nigel Nicolson, later described as 'the longest and most charming love letter in literature.'

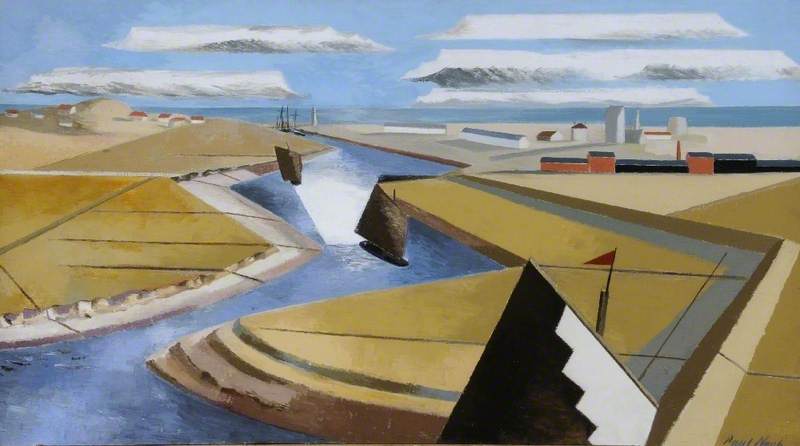

It was not only Vita who provided the inspiration for the character of Orlando and his/her gender-switching and eccentric life story – Vita's childhood home, the magnificent Knole House in Kent, also inspired the novel.

The original manuscript, inscribed 'Vita from Virginia', remains at Knole, now a National Trust property, and many aspects of the house itself, from the extensive collection of portraits of the great and good of English history, to the lavish furnishings, inspired the ancestral home described in Orlando.

As upper- and upper-middle-class women in the early twentieth century, Vita and Virginia were born into lives of material abundance but also intense social restriction. In Woolf's A Room of One's Own, she asserts the importance of a woman's ability to be financially independent for her own emancipation – something which was not easy to achieve at the time.

Both women were married to respectable men of financial means – Virginia to the publisher and author Leonard Woolf, Vita to the diplomat and writer Harold Nicolson. Though both had open marriages, which allowed them to conduct relationships with both men and women of the unconventional, forward-thinking Bloomsbury Set, such affairs had to be conducted behind the veneer of respectable marriage, and the relationships couldn't be made public.

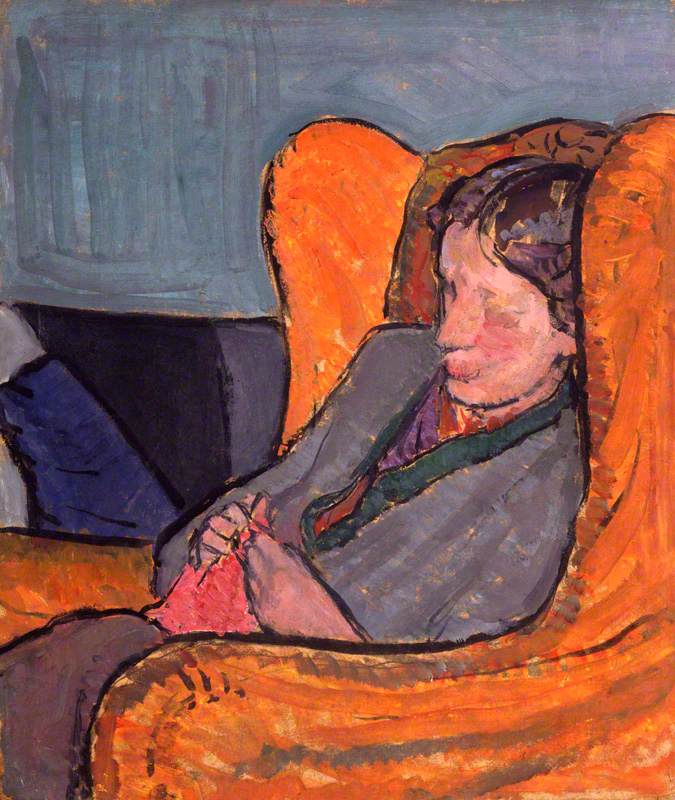

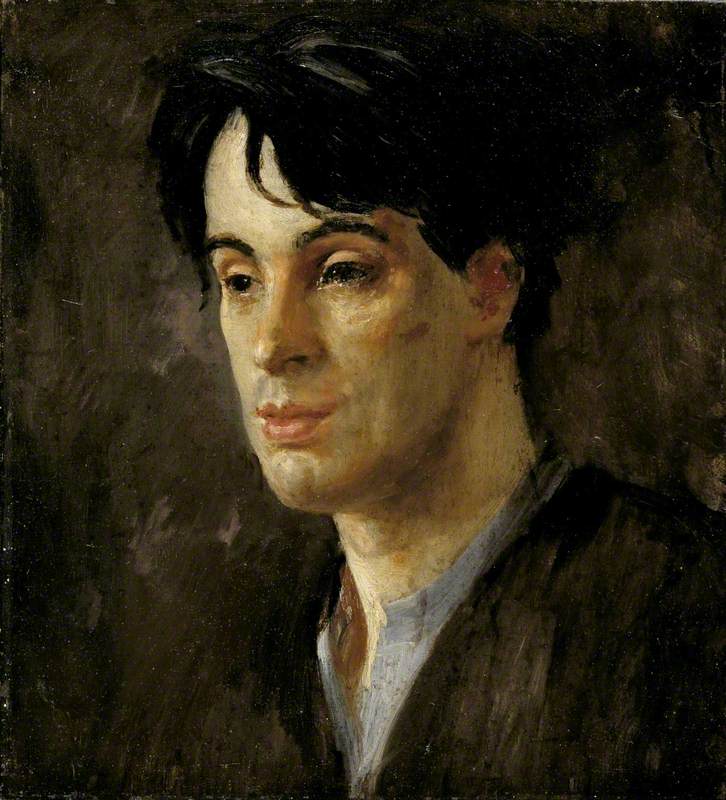

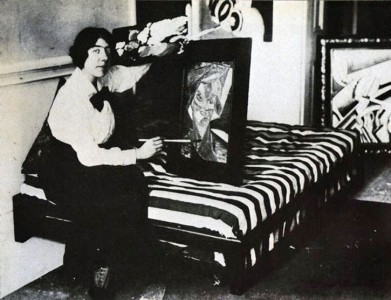

Victoria Mary 'Vita' Sackville-West (1892–1962), Later Lady Nicholson

1910

Philip Alexius de László (1869–1937)

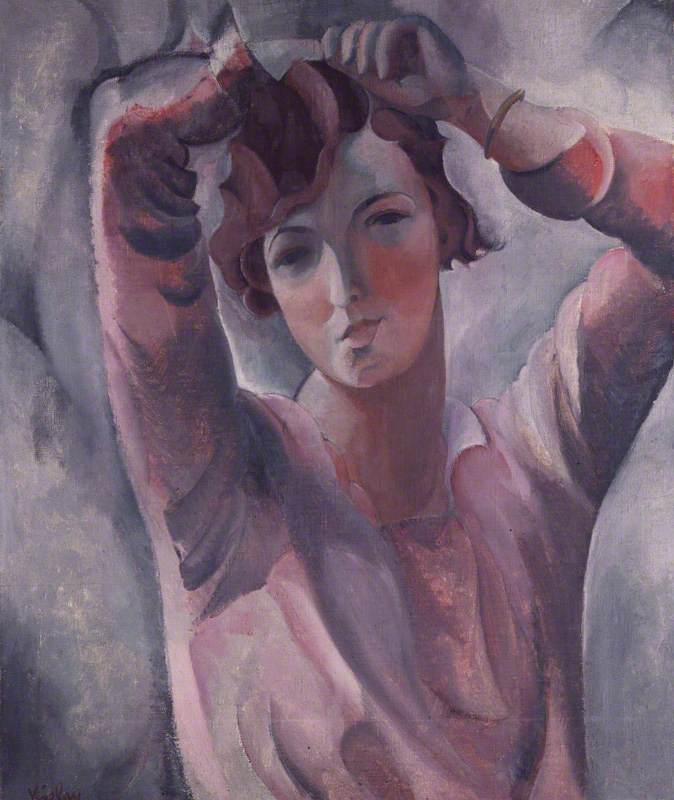

These differing personas – the upright Edwardian lady versus the louche, queer Bohemian – can be seen across different portraits of Vita. In a portrait by Philip Alexius de László, held at Sissinghurst Castle where Vita lived with her husband, she is proper and demure, rendered in blacks and browns with doe eyes and rosy cheeks, her white lace collar fastened all the way up to the jaw.

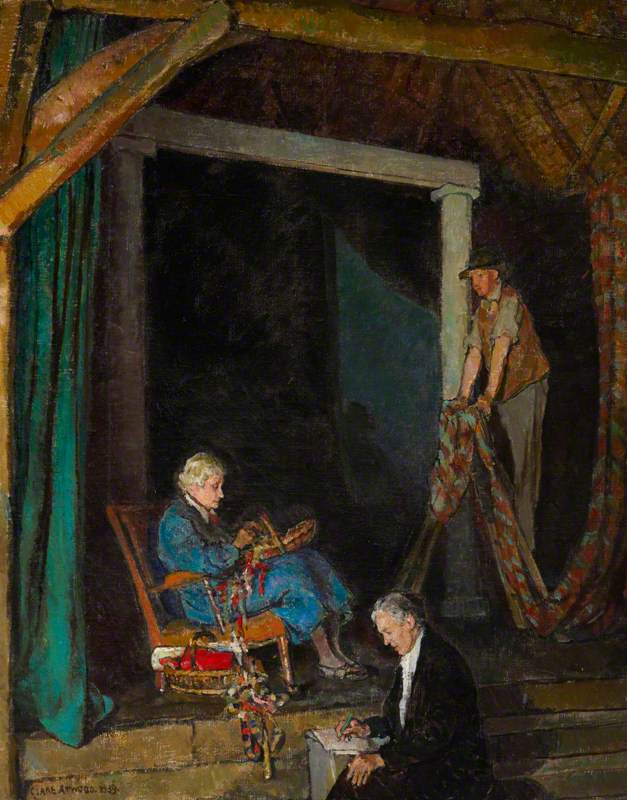

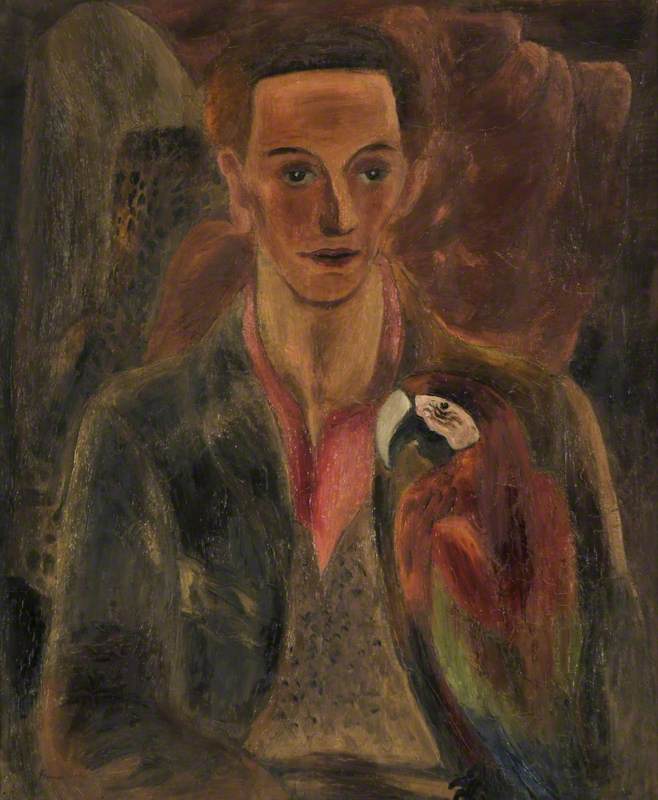

However, in an earlier portrait by Clare Atwood of an 18-year-old Vita at her beloved Knole House, she is presented as androgynous and roguish. Dressed as Portia from Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice (who famously disguises herself as a young man), Vita's short hair is a precursor of the fashionable bob of the 1920s. Her male disguise is bright red and full of rich, sensual textures. Here, she is every inch the Orlando described at the beginning of the novel, a debonair young man of Elizabethan society.

The same can be said for William Strang's Lady with a Red Hat, for which Vita modelled. Her long, handsome face holds a steady gaze, an eyebrow arched knowingly under the brim of her bright hat. One hand is placed defiantly on her hip, the other louchely dangles a book – she is relaxed, self-possessed, and worldly.

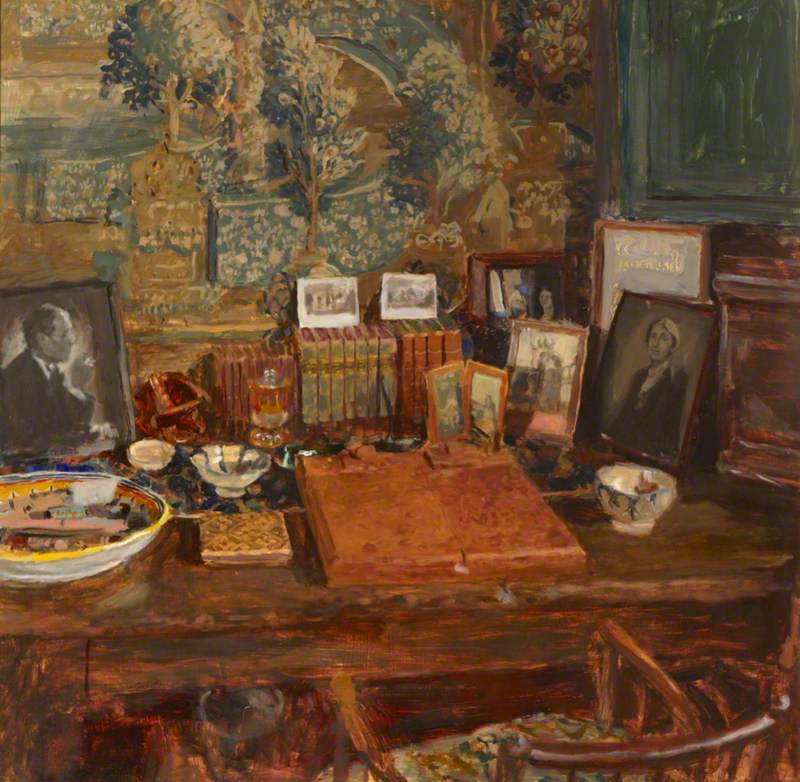

Vita Sackville-West's Writing Room in the Elizabethan Tower at Sissinghurst Castle

1990

Annie Harris (b.1945)

Knole House, Vita's childhood home, also provided inspirations for the novel. While deeply fond of the house, Vita, as a woman, was unable to inherit – the property instead passed to the first male heir. Vita felt a deep sense of loss at being unable to inherit the house, and was struck by the unfairness that the only cause was her gender. In the novel, Woolf gives her the resolution she longs for – Orlando becomes a woman and, as a woman, gets to keep her ancestral property. It is a love letter not only to Vita, but to Vita's first, lost love.

The house itself also offered ample inspiration, with its lush interiors and 500 years of history. The Brown Gallery contains an extensive collection of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century portraits of figures of the English and European courts, austere and decorated in white ruffs and thick, black fabric. These portraits, held in enormous, glistening gold frames, may have inspired the beginning of the novel, with Orlando as a member of the Elizabethan court.

Their influence lives on in the novel and in the rich, golden colours and intricate costumes of Sally Potter's 1992 film adaptation – one of the inspirations for this year's Met Gala theme, 'About Time: Fashion and Duration'.

Clare Patterson, freelance writer