This article has been kindly adapted for Art UK by Midlands Art Papers. Midlands Art Papers is a collaborative online journal, working between the University of Birmingham and 11 partner institutions to research and explore the world-class works of art and design in public collections across the Midlands. You can follow the project on Twitter: @MAP_UoB

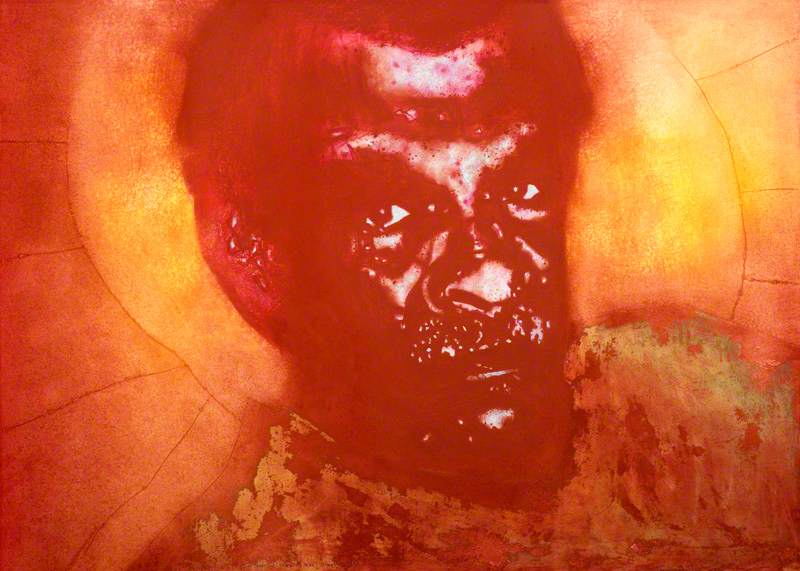

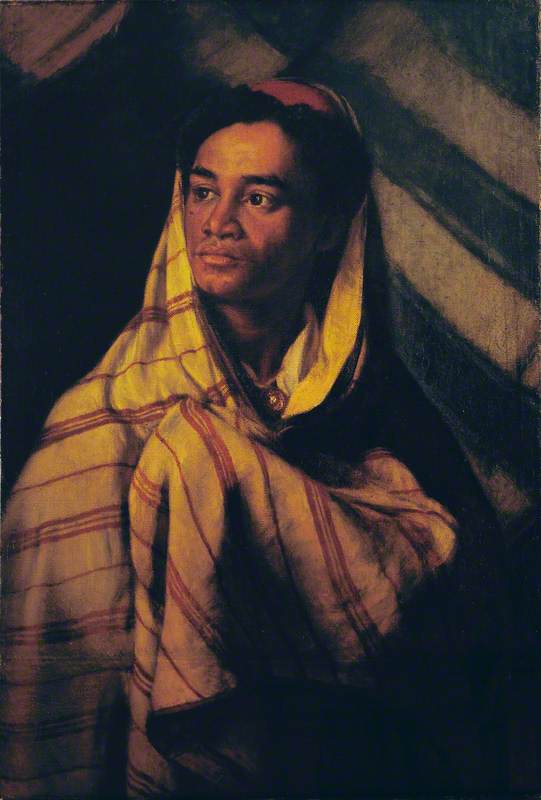

In Eugene Palmer’s Wanting To Say I, a woman meets our gaze. She is a black woman rendered in tones of black and white, and we see just her head, a portion of her neck, and a small section of her shoulder. Her hair is swept over her forehead and around her ears. She wears a pince-nez, a pair of glasses without arms, with a chain running off one side, and which appears to be attached to her ear or perhaps clipped into her hair – these were particularly popular in the nineteenth century.

The woman’s head is closely cropped by a circular, cream

Roberts’ images were considered significant for the way in which they represented African Americans – as middle-class, fashionable, self-assured, and free of the stereotypes that were imposed on black people in other representations.

There are other histories built into this painting too. The portrait of the woman is painted from a photograph taken by Richard Samuel Roberts (1880–1936), who worked in Columbia, South Carolina in the 1920s and 1930s. Roberts worked for the US Postal Service and taught himself photography in his spare time, before setting up his own studio. He was one of only a very small number of African American photographers active in the American South in these decades. His clientele appears, for the most part, to have been the developing black middle-class population of the city (of which Roberts was a part): bankers, school teachers, social workers, and so on. Roberts’ work was rediscovered and many of his photographs were published in a book, A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts, 1920–1936, in 1986.

Roberts’ images were considered significant for the way in which they represented African Americans – as middle-class, fashionable, self-assured, and free of the stereotypes that were imposed on black people in other representations. This appears to have been one of the reasons that Palmer was drawn to these photographs and began painting from them in the 1990s. His painted interpretation of the photograph was, in one sense, a way of retrieving and restoring a piece of black history. He makes this history visible and present, but it also feels distant, due to the anonymity of the sitter in the photograph. Nevertheless, Palmer lifts this woman out of her specific time and context and allows her to speak for not only her

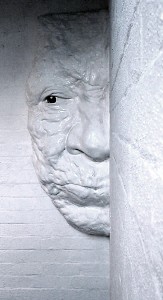

It is crucial that Palmer, in presenting the portrait in this tondo/porthole composition, encourages an awareness of looking: our look at her, and her look, back to us.

This sense that Palmer’s painting presents this woman as ‘on the move’, across time and continents, is underlined by the way she is framed – set back from the picture plane in this space that recalls the porthole of a ship. It evokes histories of migration. In Britain, the post-war increase in migration is traced to the arrival of the SS Empire Windrush from the West Indies in 1948, and this continued during the 1950s and 1960s, despite increasing controls on immigration as time wore on. Palmer was part of this movement: he was born in Kingston, Jamaica in 1955, lived through Jamaican independence in the early 1960s, and arrived in Britain as a child in 1966 to live in Chelmsley Wood in Birmingham. This experience of migration was far from unique, and not without trauma: his family was split up, as some members left first, in order to secure work and a home in Britain, before Palmer and the rest of his family could join them. Palmer has recounted how he cried throughout the aeroplane journey. Additionally, the trauma of migration inevitably has parallels with the forced migration of slavery, with journeys like Palmer’s amounting to a kind of ‘second crossing’ of the Atlantic. Like Palmer’s act of painting the photograph, the experience of migration becomes something that links black experience and black histories across time. His recovery of the traumatic memory of his own journey inevitably recovers other memories – in particular of slavery, and the ruptures in memory and time that it provoked.

The complex processes and implications of black memory are particularly important to understanding the questions raised by Wanting To Say I; they were also themes that informed understandings of

Memory is important for Wanting To Say I. Palmer evokes black histories of movement and migration

Gregory Salter, Lecturer in Art History, University of Birmingham

Further reading

Eddie Chambers, Black Artists in British Art: A History Since the 1950s, London, 2014

Morgan Quaintance, ‘Studio Visit: Eugene Palmer’, radio programme, broadcast on Resonance 104.4FM, 17 May 2015

Gregory Salter, 'Memory on the Move in Eugene Palmer's Wanting to Say I', Midlands Art Papers, Issue 1, 2017